It’s More Complicated Than A Recession

Altered Data and Selective Facts Are Providing Delusional Economic Forecasts

By Willie J. Costa & Vinh Q. Vuong

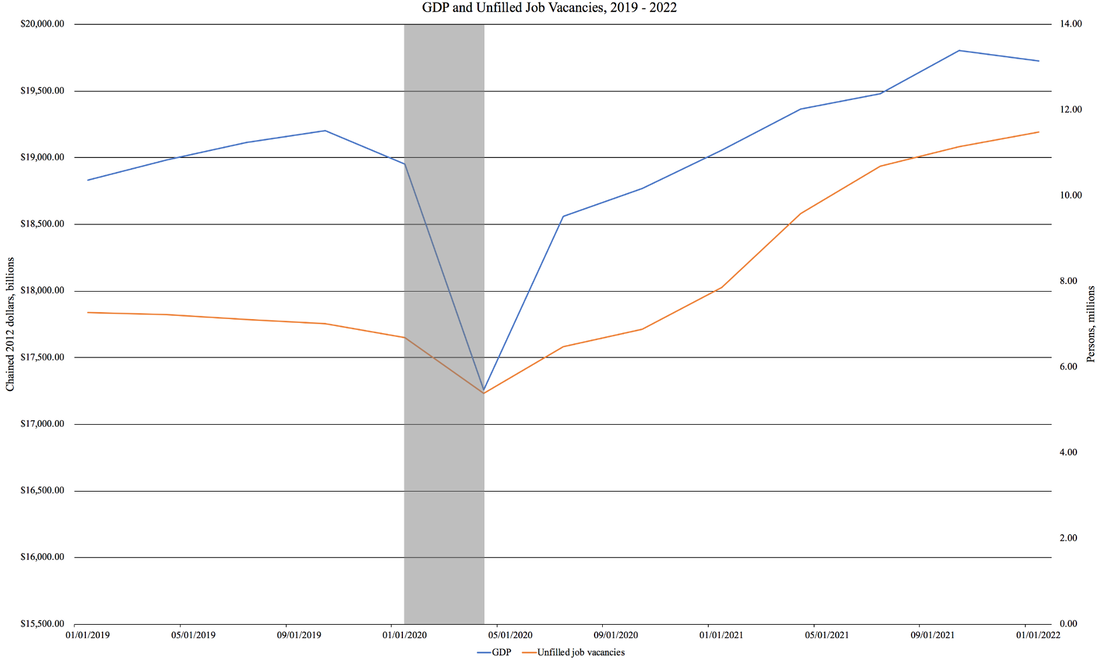

Every recession since WWII has had two things happen: GDP goes down, and unemployment goes up. Since the current economic turbulence has been likened to “things not seen in over forty years,” it might prove insightful to limit our examination to the past few decades. While no two recessions have ever been quite the same, there have been enough instances of the inverse relationship between GDP and employment (shown here as the labor participation rate) to draw meaningful conclusions.

Every recession since WWII has had two things happen: GDP goes down, and unemployment goes up. Since the current economic turbulence has been likened to “things not seen in over forty years,” it might prove insightful to limit our examination to the past few decades. While no two recessions have ever been quite the same, there have been enough instances of the inverse relationship between GDP and employment (shown here as the labor participation rate) to draw meaningful conclusions.

With few exceptions (and much more examples if the complete data set from 1947 onward is examined), the correlation between GDP and labor participation rate is readily seen: a period of flat or declining GDP growth is mirrored by a similar period of declining labor participation rate (most readily seen during the 2008 recession), and vice versa. There are outliers to this trend – the recession of the mid-1980s is an immediately apparent exception – and there are instances of inverse movement between the two variables, such as the period following the Great Recession, but generally speaking this is the case.

This relationship between GDP and employment is not entirely surprising: businesses and consumers are very well in tune with the specifics of the current economy, even if they don’t necessarily read the Wall Street Journal or are considered experts in the field of macroeconomics: they feel the motions of the economy firsthand, because they experience the immediate impacts of price and interest rate fluctuations: goods become more expensive to buy, fuel becomes more expensive to buy, fleets become more expensive to maintain, and businesses must walk the razor’s edge between absorbing cost increases and seeing profits decrease, or passing those cost increases along to the customer and risking reduced sales.

In times of economic growth and easy credit, consumers can afford to purchase more goods and services, which in turn helps drive up a business’ profits, which are then reinvested in capex and development to create new products and/or more efficient operations to capture more potential sales. Conversely, when adverse economic conditions exist, either consumers are unwilling or unable to spend as much money as they would otherwise have preferred, and/or businesses cannot afford to maintain the same level of operations as they otherwise would have; the end result is typically a decrease in spending, laying off of workers, and businesses making lower profits, which causes them to lay off workers, who then have less spending power, and so on. The primary reason why GDP and unemployment are inversely correlated is because they directly feed off of one another. Which reduction happens first – whether on the side of businesses or consumers – is not entirely relevant for this post; what is relevant is that the current economic conditions, quite simply, make no sense.

The GDP-Unemployment Contradiction

From 2021-2022, changes in GDP seemed to anticipate actions by the Fed, but interestingly the labor participation rate continues to increase while GDP continues to decline. Stated another way, both GDP and unemployment are falling at the same time:

This relationship between GDP and employment is not entirely surprising: businesses and consumers are very well in tune with the specifics of the current economy, even if they don’t necessarily read the Wall Street Journal or are considered experts in the field of macroeconomics: they feel the motions of the economy firsthand, because they experience the immediate impacts of price and interest rate fluctuations: goods become more expensive to buy, fuel becomes more expensive to buy, fleets become more expensive to maintain, and businesses must walk the razor’s edge between absorbing cost increases and seeing profits decrease, or passing those cost increases along to the customer and risking reduced sales.

In times of economic growth and easy credit, consumers can afford to purchase more goods and services, which in turn helps drive up a business’ profits, which are then reinvested in capex and development to create new products and/or more efficient operations to capture more potential sales. Conversely, when adverse economic conditions exist, either consumers are unwilling or unable to spend as much money as they would otherwise have preferred, and/or businesses cannot afford to maintain the same level of operations as they otherwise would have; the end result is typically a decrease in spending, laying off of workers, and businesses making lower profits, which causes them to lay off workers, who then have less spending power, and so on. The primary reason why GDP and unemployment are inversely correlated is because they directly feed off of one another. Which reduction happens first – whether on the side of businesses or consumers – is not entirely relevant for this post; what is relevant is that the current economic conditions, quite simply, make no sense.

The GDP-Unemployment Contradiction

From 2021-2022, changes in GDP seemed to anticipate actions by the Fed, but interestingly the labor participation rate continues to increase while GDP continues to decline. Stated another way, both GDP and unemployment are falling at the same time:

While it’s foolish to say that such a phenomenon is impossible – because we’re actually living it right now – it would not be foolish to say that such a phenomenon is unprecedented. Another factor to consider is consumer sentiment – because, once again, consumers feel the dynamics of the market even if they can’t understand them. What’s rather foreboding about consumer sentiment regarding unemployment is that it’s currently almost as abysmal as it was during 2008, and that is thanks in large part to inflation:

It’s at this point that we should mention that the effects of inflation, GDP, and unemployment are not immediate; in much the same way as a freight train may require miles to come to a stop, a system as large, powerful, and complex as the American economy has enough inertia that changes are not felt for a while. Unfortunately, this also means that actions taken to improve economic conditions will also not be felt immediately. While geopolitical concerns have certainly done their fair share to damage the global economy, the trillions of dollars of stimulus and the Fed becoming an active participant in the bond market started this particular downturn long before Russian aggression or rate hikes.

The Ugly Truth of Inflation and Worker Participation

Inflation is never “transitory” on its own; left to its own devices, inflation will run away with itself, and it’s incredibly foolish to think otherwise – so much so that by the end of 2021 the same news outlets that had been praising the Fed calling inflation transitory and not allowing it to affect policy were publishing articles decrying such criminal macroeconomic ignorance as the worst call in the history of the Fed.

Despite the downturn in GDP, corporate profit margins – normally in single-digit territory including the business-driven recession of 2001 (viz. businesses decided to cut back to rebuild margins, leading to a recession) – have increased dramatically. In fact, adjusted for inventory valuation and capital consumption, profits are at their highest in more than half a century:

The Ugly Truth of Inflation and Worker Participation

Inflation is never “transitory” on its own; left to its own devices, inflation will run away with itself, and it’s incredibly foolish to think otherwise – so much so that by the end of 2021 the same news outlets that had been praising the Fed calling inflation transitory and not allowing it to affect policy were publishing articles decrying such criminal macroeconomic ignorance as the worst call in the history of the Fed.

Despite the downturn in GDP, corporate profit margins – normally in single-digit territory including the business-driven recession of 2001 (viz. businesses decided to cut back to rebuild margins, leading to a recession) – have increased dramatically. In fact, adjusted for inventory valuation and capital consumption, profits are at their highest in more than half a century:

Corporate cash on hand has also increased dramatically – now up to $4 trillion – which is a significant downturn indicator. The reason could be simple: corporations might have already decided to simply weather the storm of a recession instead of firing workers. Given how difficult the past couple of years have been for companies to even find workers in the first place, it’s logical that they would want to keep the workers they’ve worked so hard to capture in the first place. The reality is that the labor participation rate is the lowest it’s been in 40 years; not everything has been due to the pandemic, either: despite the self-congratulatory nature of politicians winning the war on unemployment, the rate of unfilled jobs has been steadily increasing over the past decade. From the most recent Fed data, there are almost 12 million jobs that simply can’t be filled – unfilled jobs in 2019, however, when the economy was the strongest that it had been in a decade, was just seven million.

In other words, there are 4 million more job openings now, on the precipice of a recession, than there were even at the height of the last expansion. Why is that?

Some of it has to do with the simple fact that the economy is experiencing a generational change: millions of Baby Boomers are retiring, and the jobs they’re leaving are left unfilled due to a shortage of adequately-trained and properly qualified workers as well as a shortage of workers overall. The past couple of years have been a job-seeker’s market, due in part to the large demand for goods and services caused by pandemic stimulus, a labor shortage, many companies having been forced to either adopt a part-time or full-time telework arrangement for its employees, and many workers simply electing to not return to the workforce at all (one of the many reasons why the U6 unemployment rate is more informative than the often-quoted U3 rate). This is what will make the 2022/2023 recession – if one occurs – so unique.

Ordinarily there occurs what’s known as a jobless recovery: GDP recovers but companies, perhaps not entirely convinced that the recessionary period is truly over, continue to lay off workers. In other words, unemployment recovery lags GDP recovery. What the country is currently experiencing seems to be a mirror image: GDP is contracting, but the labor participation rate and the total number of available jobs both continue to increase, indicating that companies are still continuing to hire and could actually hire more.

This can probably be called a jobful downturn, which is somewhat unusual in that it subverts the natural order of economic activity. This is also clearly unsustainable – companies can’t keep hiring workers if the economy continues to contract – meaning that there are only two possible outcomes, neither of which will be particularly enjoyable:

Option 1 may stave off a recession, but it will do nothing to curb the runaway inflation that we’ve been experiencing over the past year or so. Option 2 will do absolutely nothing to stave off a recession – in fact, it will likely contribute to triggering one – and will also do nothing to curb inflation. Of course, economists are no more clairvoyant than anyone else, and it’s impossible to know beforehand which outcome will occur..

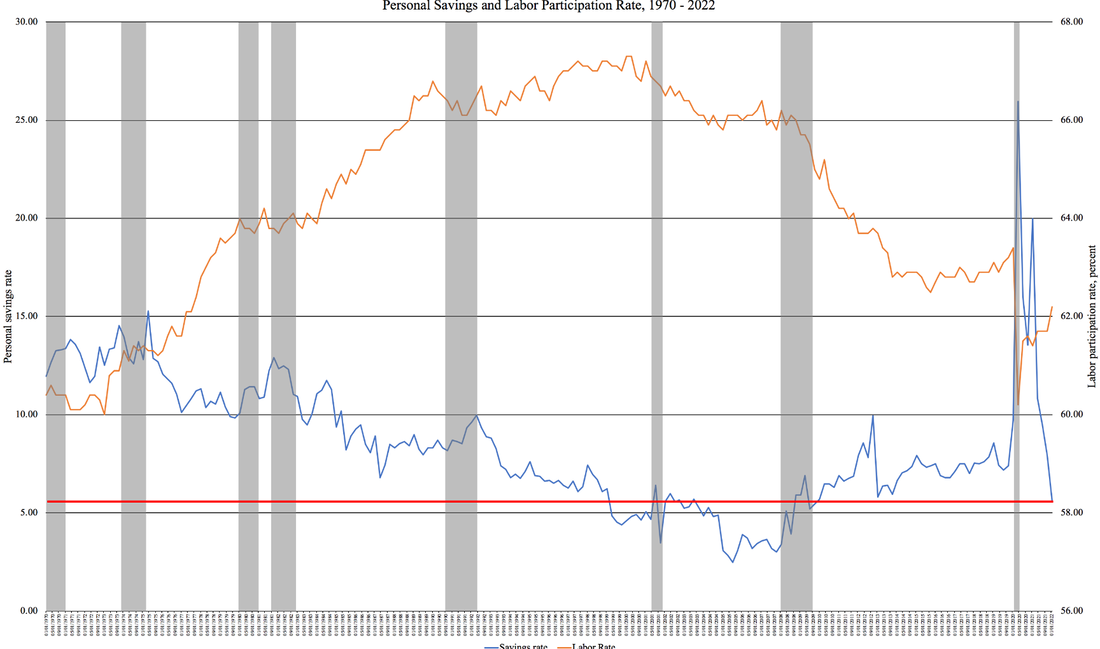

The Downturn’s Ugly Cousin

What makes the second option particularly damning is that it will trigger a recession at the worst possible moment – one in which inflation is high – and which will likely lead to stagflation, or when an economy experiences periods of high inflation and high unemployment. Of course, there is the famous Phillips curve, which states that this should not be possible since inflation (technically, an increase in the price of labor, from which an increase in inflation is a trivial conclusion) and unemployment are inversely related; historical data from the 1970s (during which the US experienced simultaneous increases in consumer prices and unemployment) have proven otherwise, as has the rise of supply-side economic theories as an alternative to Keynesian ones. Most prominent amongst the proposed theories was one espoused by Milton Friedman, who postulated that once people became accustomed to the higher rate of inflation, unemployment would again begin to rise unless the underlying cause for unemployment was addressed. What’s concerning is that the personal savings rate suggests that people are, indeed, adjusting to inflation – or at least attempting to. The personal savings rate has actually dropped to near-2008 levels, and is approaching one of the lowest points in history while labor participation continues to climb.

In essence, people are working more and saving less.

Some of it has to do with the simple fact that the economy is experiencing a generational change: millions of Baby Boomers are retiring, and the jobs they’re leaving are left unfilled due to a shortage of adequately-trained and properly qualified workers as well as a shortage of workers overall. The past couple of years have been a job-seeker’s market, due in part to the large demand for goods and services caused by pandemic stimulus, a labor shortage, many companies having been forced to either adopt a part-time or full-time telework arrangement for its employees, and many workers simply electing to not return to the workforce at all (one of the many reasons why the U6 unemployment rate is more informative than the often-quoted U3 rate). This is what will make the 2022/2023 recession – if one occurs – so unique.

Ordinarily there occurs what’s known as a jobless recovery: GDP recovers but companies, perhaps not entirely convinced that the recessionary period is truly over, continue to lay off workers. In other words, unemployment recovery lags GDP recovery. What the country is currently experiencing seems to be a mirror image: GDP is contracting, but the labor participation rate and the total number of available jobs both continue to increase, indicating that companies are still continuing to hire and could actually hire more.

This can probably be called a jobful downturn, which is somewhat unusual in that it subverts the natural order of economic activity. This is also clearly unsustainable – companies can’t keep hiring workers if the economy continues to contract – meaning that there are only two possible outcomes, neither of which will be particularly enjoyable:

- The economy can react to the continued hiring of workers and begin expanding again.

- Companies will realize that they’ve over-hired and begin cutting jobs.

Option 1 may stave off a recession, but it will do nothing to curb the runaway inflation that we’ve been experiencing over the past year or so. Option 2 will do absolutely nothing to stave off a recession – in fact, it will likely contribute to triggering one – and will also do nothing to curb inflation. Of course, economists are no more clairvoyant than anyone else, and it’s impossible to know beforehand which outcome will occur..

The Downturn’s Ugly Cousin

What makes the second option particularly damning is that it will trigger a recession at the worst possible moment – one in which inflation is high – and which will likely lead to stagflation, or when an economy experiences periods of high inflation and high unemployment. Of course, there is the famous Phillips curve, which states that this should not be possible since inflation (technically, an increase in the price of labor, from which an increase in inflation is a trivial conclusion) and unemployment are inversely related; historical data from the 1970s (during which the US experienced simultaneous increases in consumer prices and unemployment) have proven otherwise, as has the rise of supply-side economic theories as an alternative to Keynesian ones. Most prominent amongst the proposed theories was one espoused by Milton Friedman, who postulated that once people became accustomed to the higher rate of inflation, unemployment would again begin to rise unless the underlying cause for unemployment was addressed. What’s concerning is that the personal savings rate suggests that people are, indeed, adjusting to inflation – or at least attempting to. The personal savings rate has actually dropped to near-2008 levels, and is approaching one of the lowest points in history while labor participation continues to climb.

In essence, people are working more and saving less.

Whether this drop in savings is because personal consumption (as a function of quantity, not price) cannot or will not be decreased is unknown, but it places the average American in an extremely precarious position with respect to personal finances, especially if they suffer unforeseen expenses that cannot be delayed or avoided, such as required medical care. What is most concerning is that personal savings tends to decrease prior to a recession and increase during one – not surprising, given that a recession means the economy is contracting and the future of employment at the time is uncertain. But at only two points in the past 50 years the savings rate has been this low before the start of a recession, and both events saw people endure incredible economic hardship. An extremely low savings rate at the start of a stagflationary period could be cataclysmic.

Is this Inevitable?

There is also, of course, the matter of when a recession officially begins. The adage of two sequential quarters of negative GDP growth equating to a recession is an oft-quoted textbook definition that is only one of several criteria defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research, which states that a recession is a period of broad market decline, which includes declines in personal income less transfers and nonfarm employment. The “two down quarters” criterion was initially proposed by Prof. Julius Shiskin – an economist and statistician of staggering capability – who, much like the NBER, used multiple criteria to establish when a recession “officially” begins. By the declining-GDP definition, we are absolutely in a technical recession, but jobs continue to be added (as previously mentioned), and the NBER would be a laughingstock if it stated that we were in a recession right now (not that they ever would – the job of the NBER is not to predict when a recession might occur, but to retroactively define when one began and ended; they didn’t call the Great Recession a “recession” until we were already a year into it). The most reliable conclusion from these data is that, while we may not be in a recession “yet,” it absolutely appears that one is on the horizon.

Unintentional optimists who continually harp on increasing job growth as “evidence” that we’re not in a recession would do well to recall that not all recessionary initiators are triggered simultaneously – in economics, there is always a lag – and that the current climate of declining GDP combined with increasing labor participation and increasing job openings is not sustainable.

No Solutions, Only Compromises

The Fed, for its part, has been doing what it can to shrink the money supply by raising interest rates, though it is arguable that inflation is not slowing at the desired rate; increasing the required reserve rate and continuing quantitative tightening is required. But because inflation and recession are economic polar opposites, when they combine to form an unholy stagflationary environment neither the solutions to recession nor inflation can alone resolve the issue, since each solution is the inverse of the other: recessions are typically fought with stimulus, quantitative easing, and easy money, whereas inflations are combated with quantitative tightening and a constriction of the money supply.

That said, the Fed cannot fight the economic battle alone, because the current state of the economy is not an inflation-only problem: one of the historical catalysts for stagflation is supply shocks, which it may be politely said “have been concerning” as of late. Absent government intervention, stagflation may actually self-correct over time – such was the case in the 1970s, when a surge in oil prices was partly responsible for stagflationary pressure, but the gradual reduction in oil prices over time allowed the economy to emerge from the downturn.

Of course, “may self-correct” is a poor foundation upon which to build policy. Contemporary Keynesians such as Paul Krugman argue – and we would tend to agree – that the government must act quickly and swiftly to correct supply shocks without allowing unemployment to rise. Unfortunately, the reliance on the U3 rate presents an unemployment figure that is artificially low, making potential solutions politically intractable. Other available government options – specifically price controls and limits on wage increases – would be political suicide, and – as demonstrated by the US Sugar Program – price controls in the United States do not have a particularly palatable history.

Price controls – especially on gasoline and energy fuels – may be inevitable until the supply chain issues caused by Russian aggression are resolved. Naturally, this would be funded with increases in corporate taxes – including the comically-named Inflation Reduction Act, which is anything but – which would still likely trigger a recession. Of course, that is a discussion for another time.

No recession looks exactly like any other, but the 2022 recession will be unique in more than one way. Unfortunately, many of those unique characteristics will be negative and hundreds of millions of Americans will be severely impacted. Fed Chair Powell, to his credit, is fighting to control the portions of the stagflationary destruction that may be coming, but unless supply-side shocks are addressed, we as a country will remain completely helpless.

Is this Inevitable?

There is also, of course, the matter of when a recession officially begins. The adage of two sequential quarters of negative GDP growth equating to a recession is an oft-quoted textbook definition that is only one of several criteria defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research, which states that a recession is a period of broad market decline, which includes declines in personal income less transfers and nonfarm employment. The “two down quarters” criterion was initially proposed by Prof. Julius Shiskin – an economist and statistician of staggering capability – who, much like the NBER, used multiple criteria to establish when a recession “officially” begins. By the declining-GDP definition, we are absolutely in a technical recession, but jobs continue to be added (as previously mentioned), and the NBER would be a laughingstock if it stated that we were in a recession right now (not that they ever would – the job of the NBER is not to predict when a recession might occur, but to retroactively define when one began and ended; they didn’t call the Great Recession a “recession” until we were already a year into it). The most reliable conclusion from these data is that, while we may not be in a recession “yet,” it absolutely appears that one is on the horizon.

Unintentional optimists who continually harp on increasing job growth as “evidence” that we’re not in a recession would do well to recall that not all recessionary initiators are triggered simultaneously – in economics, there is always a lag – and that the current climate of declining GDP combined with increasing labor participation and increasing job openings is not sustainable.

No Solutions, Only Compromises

The Fed, for its part, has been doing what it can to shrink the money supply by raising interest rates, though it is arguable that inflation is not slowing at the desired rate; increasing the required reserve rate and continuing quantitative tightening is required. But because inflation and recession are economic polar opposites, when they combine to form an unholy stagflationary environment neither the solutions to recession nor inflation can alone resolve the issue, since each solution is the inverse of the other: recessions are typically fought with stimulus, quantitative easing, and easy money, whereas inflations are combated with quantitative tightening and a constriction of the money supply.

That said, the Fed cannot fight the economic battle alone, because the current state of the economy is not an inflation-only problem: one of the historical catalysts for stagflation is supply shocks, which it may be politely said “have been concerning” as of late. Absent government intervention, stagflation may actually self-correct over time – such was the case in the 1970s, when a surge in oil prices was partly responsible for stagflationary pressure, but the gradual reduction in oil prices over time allowed the economy to emerge from the downturn.

Of course, “may self-correct” is a poor foundation upon which to build policy. Contemporary Keynesians such as Paul Krugman argue – and we would tend to agree – that the government must act quickly and swiftly to correct supply shocks without allowing unemployment to rise. Unfortunately, the reliance on the U3 rate presents an unemployment figure that is artificially low, making potential solutions politically intractable. Other available government options – specifically price controls and limits on wage increases – would be political suicide, and – as demonstrated by the US Sugar Program – price controls in the United States do not have a particularly palatable history.

Price controls – especially on gasoline and energy fuels – may be inevitable until the supply chain issues caused by Russian aggression are resolved. Naturally, this would be funded with increases in corporate taxes – including the comically-named Inflation Reduction Act, which is anything but – which would still likely trigger a recession. Of course, that is a discussion for another time.

No recession looks exactly like any other, but the 2022 recession will be unique in more than one way. Unfortunately, many of those unique characteristics will be negative and hundreds of millions of Americans will be severely impacted. Fed Chair Powell, to his credit, is fighting to control the portions of the stagflationary destruction that may be coming, but unless supply-side shocks are addressed, we as a country will remain completely helpless.