Recession? It’s Actually Worse & Politics Is Fueling It

August 16, 2022

By Willie J. Costa & Vinh Q. Vuong

The most recent numbers for inflation are in, with year-on-year inflation for July 2022 reaching “only” 8.5% and the CPI, on a monthly basis, remained virtually flat. Sadly, this does not mean that there is “zero inflation,” despite the best wishes of the current administration; in fact, the reality is quite the opposite. Combined with the most recent unemployment figures, the inflation announcement is certainly hopeful – and it’s truly sad that the same 8.5% figure that touched off much wailing and gnashing of teeth this past March is seen as good news a scant four months later – but we’re not in the clear just yet.

Far from being “out of the woods,” the forest fire is actually closing in and our footpath through the underbrush is fading to nothing.

We have never advocated reading too much into a single data dump, and never has the need to take a holistic, strategic view of the economy been more necessary than now. Turning points in any business cycle can often occur amid perplexing, contradictory data points that take months to play out and years to resolve. Worse yet, the media feeds into the delusion to which most Americans desperately cling the way a drowning man might cling to a piece of driftwood: that a soft landing is possible, that a recession is not inevitable, and that we’re not in a recession despite one of its most critical criteria having already been met.

The truth is, a recession is not coming – it’s already here.

It’s Actually Worse

We are already in a period of stagflation – the uglier, deadlier, much more catastrophic cousin to recessions and runaway inflation. Numerous economists and investors, including Ray Dalio, have already sounded the alarm; the rest of us wait for the impending post-earthquake tsunami. What’s most damning about the current situation is that not only could it have been prevented, but it could have been wholly avoided.

Stagflation is the worst of all worlds: a period of economic stagnation combined with inflation. In other words, it’s a period of high inflation in a weak economy. Many economic models, and indeed many economists, didn’t believe such conditions were even possible; for instance, it lies nowhere on the Phillips Curve, and is so destructive because there’s no one approach to taming it that has a high likelihood of success. Ordinarily, inflation comes from a period of economic boom: interest rates are low, unemployment is low, and demand is high; this high demand allows producers to raise the prices of their products, it encourages workers to demand more money for their work (arguments regarding Universal Basic Income and a revised federal minimum wage are to be found here), and rising inflation is generally the result. Stagflation is difficult to control with monetary policy because the actions undertaken to combat one side of the problem only serve to exacerbate the other. For instance, to combat inflation, one would normally raise rates to curb demand, but in a stagflationary environment this would only worsen unemployment. In point of fact, we would argue that controlling stagflation solely via monetary policy is not only difficult, but it’s impossible.

Lessons Taught By History

Stagflation can only exist in scenarios where the unholy union of supply shocks and terrible monetary policy has been consummated. An exogenous shock to the supply of staples such as food crops or oil causes prices to increase across the board, not only for the items directly impacted – perhaps, say, the prices of wheat and corn skyrocketing due to Russian aggression – but also for downstream products that rely on those affected items – like the price of beef. The supply shock causes a scarcity of a fundamental item (usually a commodity, though not always) which then reduces the production capability of some other product, adversely affecting economic output. This is the basic foundation of stagflation: an increase in prices combined with worsening economic conditions, in this example: reduced output.

The 1970s and 1980s were textbook examples of these economic forces at work. In 1973, OPEC members agreed to enact an embargo targeted toward Canada, the Netherlands, Japan, the UK, Rhodesia, South Africa, and the US. By 1974 the price of oil had increased nearly 300% globally, from roughly $3 per barrel to $11.65 per barrel. Not only did this cause the average US retail price of a gallon of gasoline to increase over 40% – from $0.39 per gallon to $0.55 per gallon – but ancillary effects were felt throughout the nation. This included not only nationwide gasoline rationing (and Nixon asking gasoline retailers to voluntarily stop selling gasoline on Saturday nights and Sundays, leading to lines and bedlam across the country), but also resulted in nationwide energy rationing – with some towns like Harlan, Iowa banning Christmas lights; Macy’s, Saks, and Lord & Taylor in New York City refusing to light outdoor decorations; the Washington Cathedral turning off all lights (with the merciful exception of allowing the curator to turn on lights when visiting the crypt); and in a show of solidarity, the Nixon White House family tree trimmed only in tinsel, with the national tree across the street illuminated by five spotlights instead of 9,000 bulbs.

This situation was the very definition of stagflation. Fortunately, the US economy – and indeed, the world’s – was saved by a collapse in oil prices. Unfortunately, waiting for external shocks to rectify the effects of previous external shocks makes for poor policy.

The second cause can also be seen historically: that of poor management of monetary policy. In a stagflationary environment, the worst possible thing one can do is overstimulate the economy, usually via money printing, whereby the central bank prints lots of money to stimulate economic growth and stave off the worst of the recessionary aspects of stagflation. Printing money is itself inflationary, and will only worsen the situation. The worst possible scenario in this situation is also the most likely outcome: people not only become accustomed to inflationary pressure, but come to expect it. Then they begin to act accordingly, with predictably disastrous results.

For example, during the Zimbabwean hyperinflation crisis of 2007-2009, store owners were raising prices three times per day simply because of expected inflation; note that this was not due to official releases of inflation measures, which were absolutely not being released three times per day, but was an action undertaken simply on assumption. People would use plastic currencies out of fear that paper currency would be worthless by the time it was printed, and workers were asking to be paid multiple times per day so they could spend their money before it lost even more value. The end result, as one might imagine, made inflation a self-fulfilling prophecy: businesses raised prices, and consumers – expecting prices to continue to rise, oftentimes within the same day – began spending money as soon as they could get it (viz. a low savings rate). The annual inflation rate spiked to 1,281% and stayed at over 1,000% every month from April 2006 through February 2007. Harare workers found that their entire salary was consumed by the cost of commuting to and from work. The issuance of a 500 million ZWD note (worth about $3 USD at the time) and President Mugabe declaring inflation illegal (effectively instituting a price freeze, which itself does nothing to counter inflation) did nothing to solve the problem: inflation remained high regardless of employment or economic output.

The exacerbation of inflationary pressure via poor monetary policy also occurred in the US during the aforementioned 1970s glut of economic misery. The Vietnam conflict was consuming a great deal of the economic output of the nation, and in a bid for reelection, Nixon vastly expanded social security and other services. The abandonment of the gold standard in 1971 meant that the central bank was suddenly free to print as much money as they pleased, with M1 growing from $228 billion in 1971 to $249 billion in 1972 – a 9.2% increase within a single year; similarly, M2 (which also includes measures of retail sales, savings, and small deposits) grew even faster, from $710 billion to $802 billion – a 13% increase – within the same time period. If this sounds horrific, you’re correct – and it’s also a faster rate of inflation than the US experienced even as a result of the recent money-printing irresponsibility caused by covid. In an effort to curb inflation – and perhaps unwittingly prove that the invisible hand is best left alone – Nixon implemented wage & price controls to help curb inflation; while this did help curb inflation, it unfortunately came at the cost of food shortages, and created situations so extreme that not only were shelves devoid of food, but farmers were actually drowning their own chickens rather than selling them at a loss. When the negative effects of price controls became painfully evident to everyone, the price controls were removed, causing a “catch-up” period where businesses immediately raised prices in an attempt to recover lost profits, whiplashing the economy back into an inflationary state.

Volcker was ultimately the only reason why the American economy was not only able to recover, but able to be saved at all. That his actions earned him few friends, and much professional derision, but were undertaken anyway is a testament to the necessity of courage and ethical fortitude that we are all taught as children, but which is often forgotten through puberty.

Yet We Continue To Forget Our Lessons From History

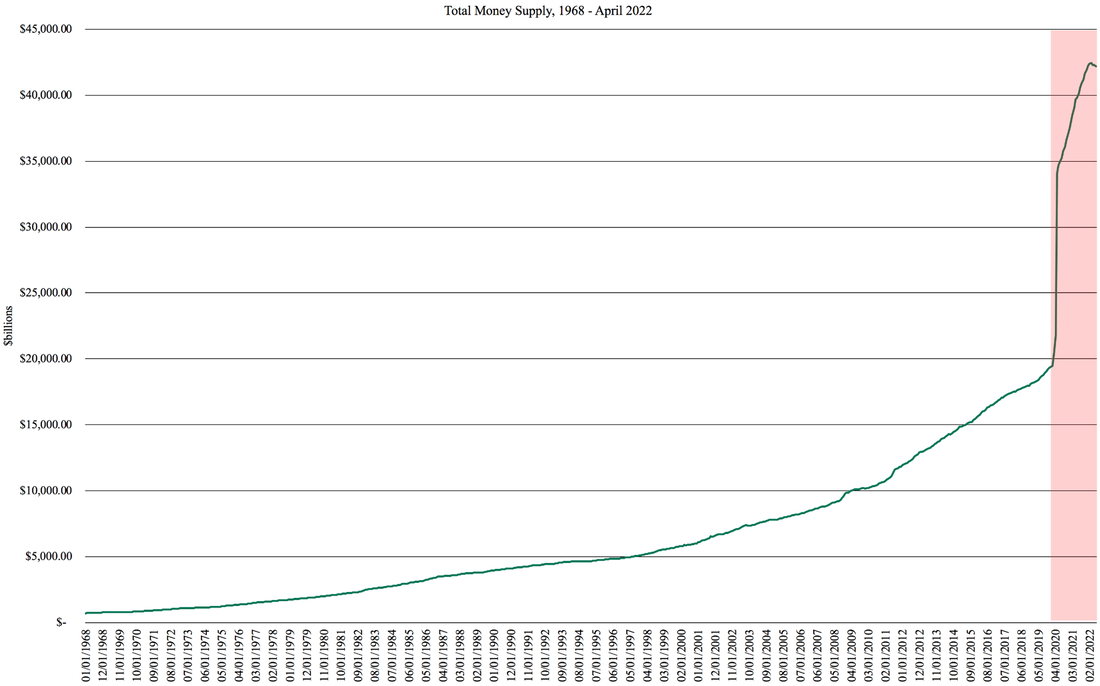

The astute reader will notice several similarities between the historical examples and the current situation facing the American economy: oil and gas supply shocks may be relatively recent, but logistics constraints have endured for almost three years now with no end in sight. The enormous period of money printing may have spawned memes – and may indicate one of the few times in recent history where the US population en masse became interested in macroeconomics – but the effects on the economy have been devastating. In fact, of the entire money supply between 1970 and 2022, more than half of it came into existence during the covid stimulus period:

By Willie J. Costa & Vinh Q. Vuong

The most recent numbers for inflation are in, with year-on-year inflation for July 2022 reaching “only” 8.5% and the CPI, on a monthly basis, remained virtually flat. Sadly, this does not mean that there is “zero inflation,” despite the best wishes of the current administration; in fact, the reality is quite the opposite. Combined with the most recent unemployment figures, the inflation announcement is certainly hopeful – and it’s truly sad that the same 8.5% figure that touched off much wailing and gnashing of teeth this past March is seen as good news a scant four months later – but we’re not in the clear just yet.

Far from being “out of the woods,” the forest fire is actually closing in and our footpath through the underbrush is fading to nothing.

We have never advocated reading too much into a single data dump, and never has the need to take a holistic, strategic view of the economy been more necessary than now. Turning points in any business cycle can often occur amid perplexing, contradictory data points that take months to play out and years to resolve. Worse yet, the media feeds into the delusion to which most Americans desperately cling the way a drowning man might cling to a piece of driftwood: that a soft landing is possible, that a recession is not inevitable, and that we’re not in a recession despite one of its most critical criteria having already been met.

The truth is, a recession is not coming – it’s already here.

It’s Actually Worse

We are already in a period of stagflation – the uglier, deadlier, much more catastrophic cousin to recessions and runaway inflation. Numerous economists and investors, including Ray Dalio, have already sounded the alarm; the rest of us wait for the impending post-earthquake tsunami. What’s most damning about the current situation is that not only could it have been prevented, but it could have been wholly avoided.

Stagflation is the worst of all worlds: a period of economic stagnation combined with inflation. In other words, it’s a period of high inflation in a weak economy. Many economic models, and indeed many economists, didn’t believe such conditions were even possible; for instance, it lies nowhere on the Phillips Curve, and is so destructive because there’s no one approach to taming it that has a high likelihood of success. Ordinarily, inflation comes from a period of economic boom: interest rates are low, unemployment is low, and demand is high; this high demand allows producers to raise the prices of their products, it encourages workers to demand more money for their work (arguments regarding Universal Basic Income and a revised federal minimum wage are to be found here), and rising inflation is generally the result. Stagflation is difficult to control with monetary policy because the actions undertaken to combat one side of the problem only serve to exacerbate the other. For instance, to combat inflation, one would normally raise rates to curb demand, but in a stagflationary environment this would only worsen unemployment. In point of fact, we would argue that controlling stagflation solely via monetary policy is not only difficult, but it’s impossible.

Lessons Taught By History

Stagflation can only exist in scenarios where the unholy union of supply shocks and terrible monetary policy has been consummated. An exogenous shock to the supply of staples such as food crops or oil causes prices to increase across the board, not only for the items directly impacted – perhaps, say, the prices of wheat and corn skyrocketing due to Russian aggression – but also for downstream products that rely on those affected items – like the price of beef. The supply shock causes a scarcity of a fundamental item (usually a commodity, though not always) which then reduces the production capability of some other product, adversely affecting economic output. This is the basic foundation of stagflation: an increase in prices combined with worsening economic conditions, in this example: reduced output.

The 1970s and 1980s were textbook examples of these economic forces at work. In 1973, OPEC members agreed to enact an embargo targeted toward Canada, the Netherlands, Japan, the UK, Rhodesia, South Africa, and the US. By 1974 the price of oil had increased nearly 300% globally, from roughly $3 per barrel to $11.65 per barrel. Not only did this cause the average US retail price of a gallon of gasoline to increase over 40% – from $0.39 per gallon to $0.55 per gallon – but ancillary effects were felt throughout the nation. This included not only nationwide gasoline rationing (and Nixon asking gasoline retailers to voluntarily stop selling gasoline on Saturday nights and Sundays, leading to lines and bedlam across the country), but also resulted in nationwide energy rationing – with some towns like Harlan, Iowa banning Christmas lights; Macy’s, Saks, and Lord & Taylor in New York City refusing to light outdoor decorations; the Washington Cathedral turning off all lights (with the merciful exception of allowing the curator to turn on lights when visiting the crypt); and in a show of solidarity, the Nixon White House family tree trimmed only in tinsel, with the national tree across the street illuminated by five spotlights instead of 9,000 bulbs.

This situation was the very definition of stagflation. Fortunately, the US economy – and indeed, the world’s – was saved by a collapse in oil prices. Unfortunately, waiting for external shocks to rectify the effects of previous external shocks makes for poor policy.

The second cause can also be seen historically: that of poor management of monetary policy. In a stagflationary environment, the worst possible thing one can do is overstimulate the economy, usually via money printing, whereby the central bank prints lots of money to stimulate economic growth and stave off the worst of the recessionary aspects of stagflation. Printing money is itself inflationary, and will only worsen the situation. The worst possible scenario in this situation is also the most likely outcome: people not only become accustomed to inflationary pressure, but come to expect it. Then they begin to act accordingly, with predictably disastrous results.

For example, during the Zimbabwean hyperinflation crisis of 2007-2009, store owners were raising prices three times per day simply because of expected inflation; note that this was not due to official releases of inflation measures, which were absolutely not being released three times per day, but was an action undertaken simply on assumption. People would use plastic currencies out of fear that paper currency would be worthless by the time it was printed, and workers were asking to be paid multiple times per day so they could spend their money before it lost even more value. The end result, as one might imagine, made inflation a self-fulfilling prophecy: businesses raised prices, and consumers – expecting prices to continue to rise, oftentimes within the same day – began spending money as soon as they could get it (viz. a low savings rate). The annual inflation rate spiked to 1,281% and stayed at over 1,000% every month from April 2006 through February 2007. Harare workers found that their entire salary was consumed by the cost of commuting to and from work. The issuance of a 500 million ZWD note (worth about $3 USD at the time) and President Mugabe declaring inflation illegal (effectively instituting a price freeze, which itself does nothing to counter inflation) did nothing to solve the problem: inflation remained high regardless of employment or economic output.

The exacerbation of inflationary pressure via poor monetary policy also occurred in the US during the aforementioned 1970s glut of economic misery. The Vietnam conflict was consuming a great deal of the economic output of the nation, and in a bid for reelection, Nixon vastly expanded social security and other services. The abandonment of the gold standard in 1971 meant that the central bank was suddenly free to print as much money as they pleased, with M1 growing from $228 billion in 1971 to $249 billion in 1972 – a 9.2% increase within a single year; similarly, M2 (which also includes measures of retail sales, savings, and small deposits) grew even faster, from $710 billion to $802 billion – a 13% increase – within the same time period. If this sounds horrific, you’re correct – and it’s also a faster rate of inflation than the US experienced even as a result of the recent money-printing irresponsibility caused by covid. In an effort to curb inflation – and perhaps unwittingly prove that the invisible hand is best left alone – Nixon implemented wage & price controls to help curb inflation; while this did help curb inflation, it unfortunately came at the cost of food shortages, and created situations so extreme that not only were shelves devoid of food, but farmers were actually drowning their own chickens rather than selling them at a loss. When the negative effects of price controls became painfully evident to everyone, the price controls were removed, causing a “catch-up” period where businesses immediately raised prices in an attempt to recover lost profits, whiplashing the economy back into an inflationary state.

Volcker was ultimately the only reason why the American economy was not only able to recover, but able to be saved at all. That his actions earned him few friends, and much professional derision, but were undertaken anyway is a testament to the necessity of courage and ethical fortitude that we are all taught as children, but which is often forgotten through puberty.

Yet We Continue To Forget Our Lessons From History

The astute reader will notice several similarities between the historical examples and the current situation facing the American economy: oil and gas supply shocks may be relatively recent, but logistics constraints have endured for almost three years now with no end in sight. The enormous period of money printing may have spawned memes – and may indicate one of the few times in recent history where the US population en masse became interested in macroeconomics – but the effects on the economy have been devastating. In fact, of the entire money supply between 1970 and 2022, more than half of it came into existence during the covid stimulus period:

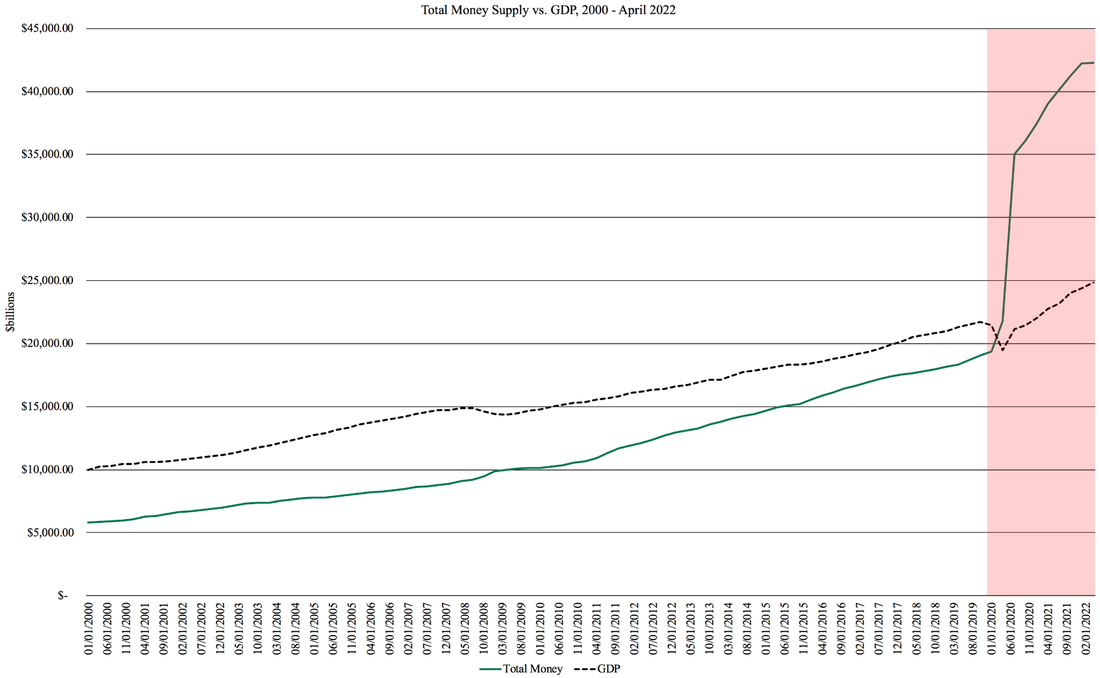

The truly staggering result is seen when one considers the total money supply as a percentage of GDP:

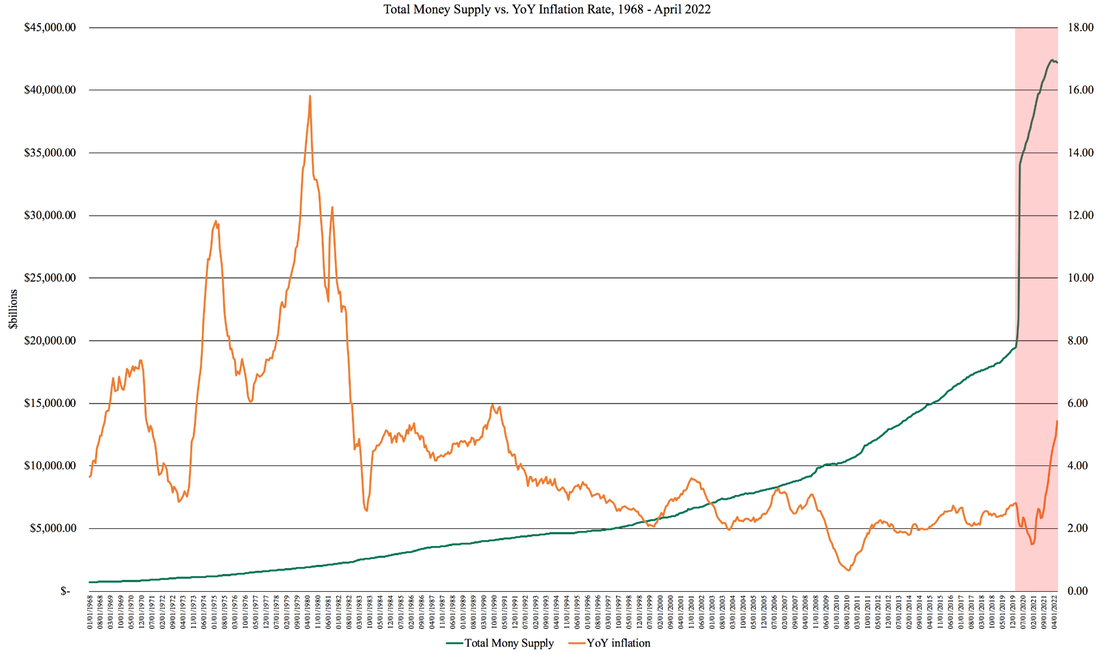

The relationship between GDP and money supply has not once, in 50 years, inverted until covid. As a crude explanation, the Fed has literally printed money that the entire economic output of the United States – the largest and most powerful economy in the history of the world – cannot match. That rampant inflation is the end result of such policy is a conclusion so readily obvious that the mere statement of it should be considered a crime of facile explicability, yet during the period immediately following the hyperactivity of the money printer, inflation actually decreased:

This is also a trivial conclusion, because it ignores two fundamental tenets of economics:

While certain actions, such as the Paycheck Protection Program, were essential to maintaining the economic integrity of the average American, the money printing was poorly timed and came at a period of severe GDP decline. The cause of the rampant inflation, from which we are still suffering, was not caused by a stimulation of the economy at a time of negative growth, but of overstimulation at the worst possible time. Put simply, it should have been either the PPP or the stimulus checks, not both, and certainly not continuing to print money after GDP had recovered.

The Fed now finds itself in a bit of a pickle; as previously mentioned, the savings rate is abysmal and there are actually more jobs now than at the height of the last economic expansionary period. Despite optimistic reports and glib celebrations by politicians of a certain leaning, adding jobs to an economy doesn’t actually mean anything if those jobs are not filled. A decline in savings rate goes hand in hand with an increase in the inability of the average American to withstand a shock to their financial wellbeing, such as having work hours reduced or becoming unemployed. This is exacerbated by the increasing reliance on credit – an immediate and unfortunate reality for an uncomfortable majority of Americans – as it is essentially delaying the symptoms of today’s pain until later, while never actually addressing the cause of it. Consumer borrowing actually increased by over $40 billion (about $14.8 billion in revolving credit, which includes credit cards, and $25.4 billion in non-revolving credit) in June 2022 from one month prior – the second-highest increase in history. It is highly likely that we will recover from the current catastrophe only to find ourselves facing a massive consumer debt crisis – a crisis which will, unlike inflation, exacerbate nonlinearly due to the mechanics of compound interest.

We are most certainly and unequivocally in a technical recession, during a period of high inflation. We are in stagflation, by any measure of the term. We may not be in a “real” recession – however the zeitgeist chooses to define that term – but technicalities will be of cold comfort when one finds themselves out of a job, out of a home, and facing an empty plate.

Action and Aboulia

The Fed find themselves in an unenviable position, painted into the figurative corner and forced to try and waltz through the thin center of both dooms while only being able to control half of the causes of our current predicament. Showing that misery loves company, the Fed is not alone in its precarious position: the political and wealth gap issues at play have created more of a playground for political ideologies than a need for actual solutions.

Everyone needs more money, but leaders are hesitant to do anything about it, content to make just enough promises to reach the next election cycle. Taxation is normally how this problem is resolved, but the effects would be financially devastating if enacted now. The “easy” way to resolve any economic issue – printing money – is usually favored because few people truly pay attention, and the consequences are usually delayed, as we have experienced presently. But raising rates and decreasing the money supply when the populace is already struggling would be political suicide.

That doesn’t mean it’s the wrong course of action. Much has been said about Volcker doubling or tripling the Federal Funds Rate and its effect on the economy; that has, in fact, been much of the justification for the meager rate hikes enacted by Chair Powell. Unfortunately, this line of thinking is seriously flawed: whether rates are tripled, quadrupled, quintupled, or increased 100x is irrelevant, because the percentage of rate increases has absolutely zero effect on the economy. Stated another way, for any condition of GDP output, inflation, and money supply, there exists a rate at which enough demand destruction has been enacted that inflation begins to make measurable downward movement. This rate may be twice the current value, or ten times the current value, but the scale of “inflation-killing rate” relative to “current rate” is a useless measure: what matters is results.

Volcker may have caused a nasty recession in the early 1980s (where unemployment boomed to almost 11% – still less than the nearly 15% the US experienced in 2020) by hiking rates to 20%, but it did kill inflation – and the lingering stagflation of the 1970s – despite the professional derision that such actions earned him. Foreign creditors were also squeezed, putting them into decadal depressions, but inflation is only reduced via painful squeezing. The higher the inflation, the more necessary and more painful the squeeze. Had Volcker meagerly parlayed out 50-bps hikes while asking inflation “Please, sir, may we have less of you?”, we’d likely still be recovering from the fallout of the 1970s’ destitution some forty-plus years later.

The current weak-handed approach is only prolonging the inevitable. If there is insufficient political willpower to institute Volckerian measures, the current situation will only be made worse. So little gets done to address either side of the stagflation problem that, essentially, nothing is being done at all. Demand destruction at a time when people already don’t have enough money due to inflation is likely such a painful outcome that it is merely untenable to the country’s leadership, which seems enamored with clinging to the hope of a better tomorrow while the catastrophe of today goes unheeded. Consumers themselves may be the deciding factor in when – not if – the inevitable recession will occur, as they “choose violence” rather than cutting back on spending. To an extent, they should hardly be blamed – it is human nature to resort to familiar and comforting behaviors in times of stress, no matter how destructive those behaviors might be – but a laissez faire attitude on the part of our country’s leadership in the face of financial damnation is hardly a commendable character trait.

This is the time to put politics aside or we’ll be the North American version of Venezuela.

- Inflation didn’t decrease because of the injection of capital, but rather from the decrease in GDP that was caused by the start of the global pandemic. The decrease in GDP was itself a deflationary action, arguably one which was resolved all too well during the subsequent 18 months.

- When enacting monetary policy, one must recall that there is always a delay: consequence lags action, sometimes by a significant degree.

While certain actions, such as the Paycheck Protection Program, were essential to maintaining the economic integrity of the average American, the money printing was poorly timed and came at a period of severe GDP decline. The cause of the rampant inflation, from which we are still suffering, was not caused by a stimulation of the economy at a time of negative growth, but of overstimulation at the worst possible time. Put simply, it should have been either the PPP or the stimulus checks, not both, and certainly not continuing to print money after GDP had recovered.

The Fed now finds itself in a bit of a pickle; as previously mentioned, the savings rate is abysmal and there are actually more jobs now than at the height of the last economic expansionary period. Despite optimistic reports and glib celebrations by politicians of a certain leaning, adding jobs to an economy doesn’t actually mean anything if those jobs are not filled. A decline in savings rate goes hand in hand with an increase in the inability of the average American to withstand a shock to their financial wellbeing, such as having work hours reduced or becoming unemployed. This is exacerbated by the increasing reliance on credit – an immediate and unfortunate reality for an uncomfortable majority of Americans – as it is essentially delaying the symptoms of today’s pain until later, while never actually addressing the cause of it. Consumer borrowing actually increased by over $40 billion (about $14.8 billion in revolving credit, which includes credit cards, and $25.4 billion in non-revolving credit) in June 2022 from one month prior – the second-highest increase in history. It is highly likely that we will recover from the current catastrophe only to find ourselves facing a massive consumer debt crisis – a crisis which will, unlike inflation, exacerbate nonlinearly due to the mechanics of compound interest.

We are most certainly and unequivocally in a technical recession, during a period of high inflation. We are in stagflation, by any measure of the term. We may not be in a “real” recession – however the zeitgeist chooses to define that term – but technicalities will be of cold comfort when one finds themselves out of a job, out of a home, and facing an empty plate.

Action and Aboulia

The Fed find themselves in an unenviable position, painted into the figurative corner and forced to try and waltz through the thin center of both dooms while only being able to control half of the causes of our current predicament. Showing that misery loves company, the Fed is not alone in its precarious position: the political and wealth gap issues at play have created more of a playground for political ideologies than a need for actual solutions.

Everyone needs more money, but leaders are hesitant to do anything about it, content to make just enough promises to reach the next election cycle. Taxation is normally how this problem is resolved, but the effects would be financially devastating if enacted now. The “easy” way to resolve any economic issue – printing money – is usually favored because few people truly pay attention, and the consequences are usually delayed, as we have experienced presently. But raising rates and decreasing the money supply when the populace is already struggling would be political suicide.

That doesn’t mean it’s the wrong course of action. Much has been said about Volcker doubling or tripling the Federal Funds Rate and its effect on the economy; that has, in fact, been much of the justification for the meager rate hikes enacted by Chair Powell. Unfortunately, this line of thinking is seriously flawed: whether rates are tripled, quadrupled, quintupled, or increased 100x is irrelevant, because the percentage of rate increases has absolutely zero effect on the economy. Stated another way, for any condition of GDP output, inflation, and money supply, there exists a rate at which enough demand destruction has been enacted that inflation begins to make measurable downward movement. This rate may be twice the current value, or ten times the current value, but the scale of “inflation-killing rate” relative to “current rate” is a useless measure: what matters is results.

Volcker may have caused a nasty recession in the early 1980s (where unemployment boomed to almost 11% – still less than the nearly 15% the US experienced in 2020) by hiking rates to 20%, but it did kill inflation – and the lingering stagflation of the 1970s – despite the professional derision that such actions earned him. Foreign creditors were also squeezed, putting them into decadal depressions, but inflation is only reduced via painful squeezing. The higher the inflation, the more necessary and more painful the squeeze. Had Volcker meagerly parlayed out 50-bps hikes while asking inflation “Please, sir, may we have less of you?”, we’d likely still be recovering from the fallout of the 1970s’ destitution some forty-plus years later.

The current weak-handed approach is only prolonging the inevitable. If there is insufficient political willpower to institute Volckerian measures, the current situation will only be made worse. So little gets done to address either side of the stagflation problem that, essentially, nothing is being done at all. Demand destruction at a time when people already don’t have enough money due to inflation is likely such a painful outcome that it is merely untenable to the country’s leadership, which seems enamored with clinging to the hope of a better tomorrow while the catastrophe of today goes unheeded. Consumers themselves may be the deciding factor in when – not if – the inevitable recession will occur, as they “choose violence” rather than cutting back on spending. To an extent, they should hardly be blamed – it is human nature to resort to familiar and comforting behaviors in times of stress, no matter how destructive those behaviors might be – but a laissez faire attitude on the part of our country’s leadership in the face of financial damnation is hardly a commendable character trait.

This is the time to put politics aside or we’ll be the North American version of Venezuela.

Subscribe to updates or if you have any questions or comments, please email us at: [email protected]

Follow our CEO: @thevinhvuong

Follow Garrison Fathom: @garrisonfathom

Follow our CEO: @thevinhvuong

Follow Garrison Fathom: @garrisonfathom