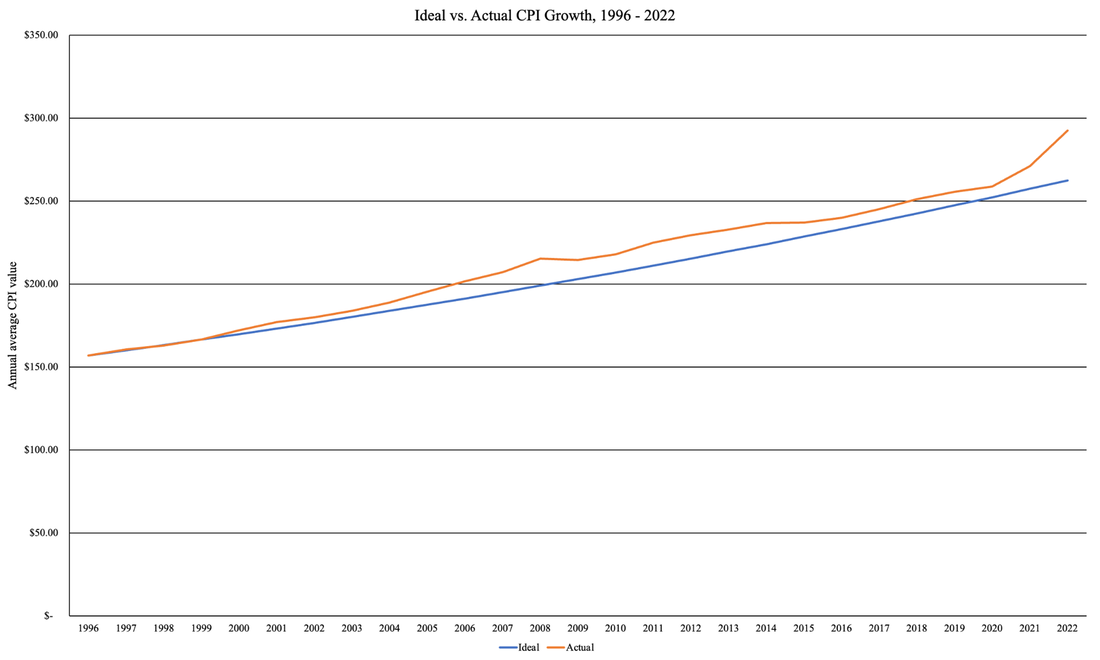

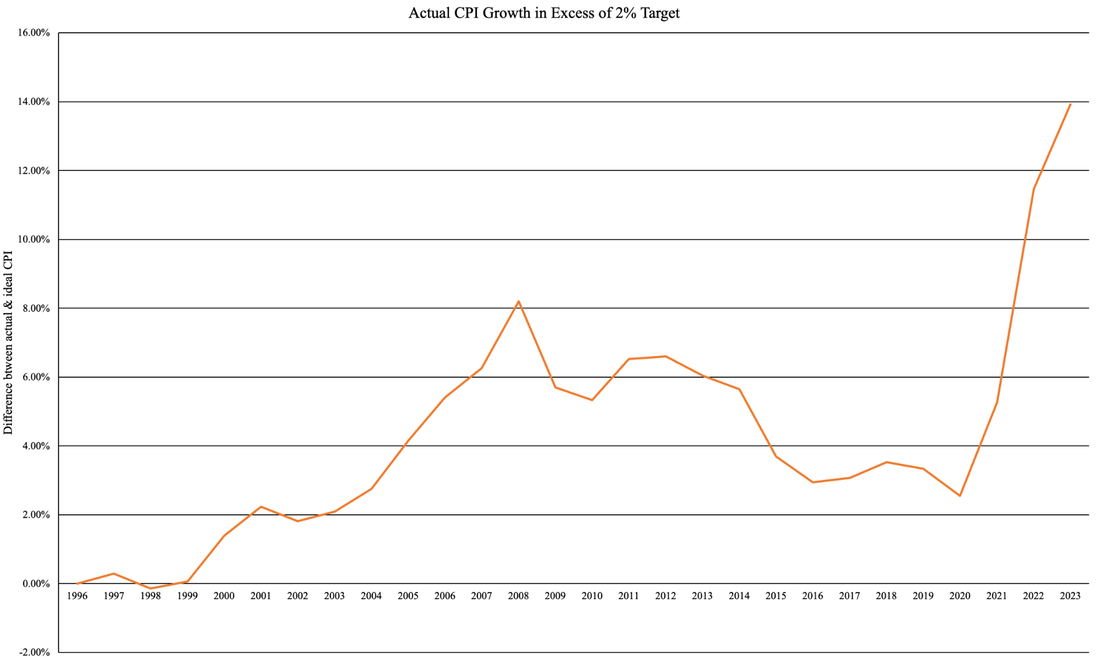

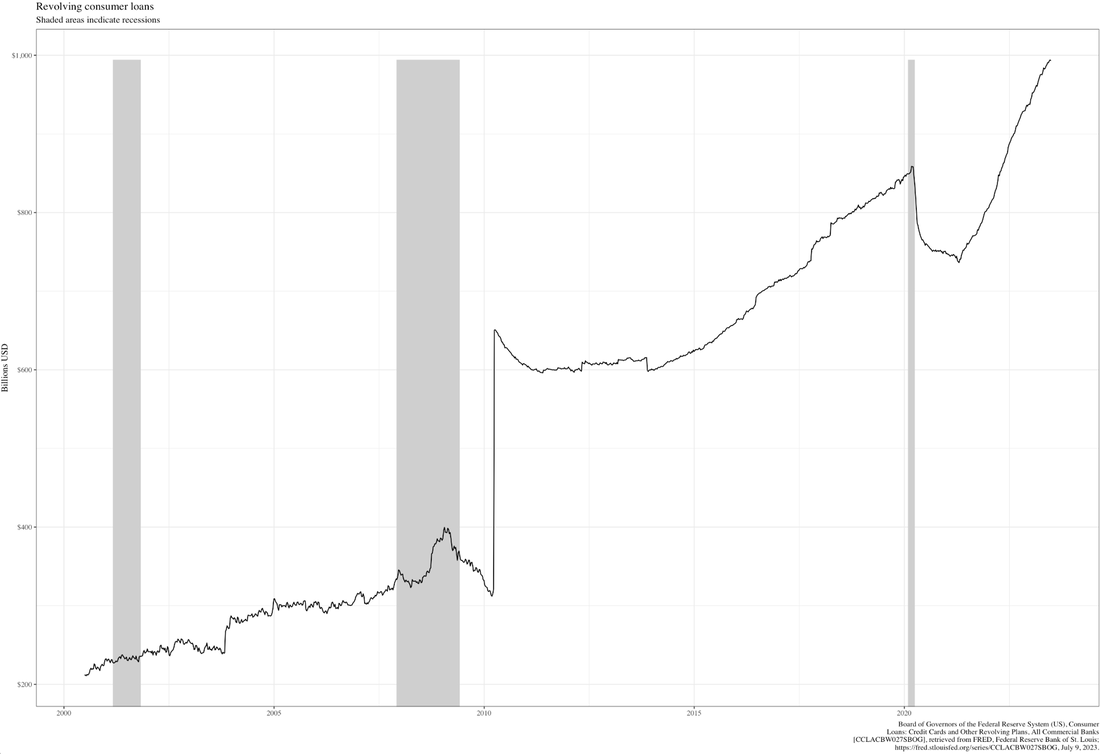

Faulty conclusions drawn from sparse data lead to a false sense of securityBy Willie Costa & Vinh Vuong The most recent numbers show that inflation slid below a two-year low, but hope that this signals the end of inflation are misplaced and completely inconsistent with reality. CPI inflation is now one-third of what it was last year, and in no way does this mean that the fight against pricing pressure is over. Both markets and economists are calling for the end of rate hikes (although the FOMC will still likely hike at its July 25-26 meeting), with short-term Treasury yields dropping, stocks rising, and the dollar falling to its lowest level in more than a year. Undoubtedly, inflation remains above the Fed’s 2% target; unfortunately, accomplishing this last bit might be the most difficult, and Americans are still feeling with every transaction. Historical data suggest that this pain is unlikely to end anytime soon: in fact, if one looks at the actual growth of CPI since the Fed began using its 2% annual inflation target in 1996 (a target that several central banks – including the Bank of Canada, Riksbank, the Bank of Japan, and the European Central Bank – all use as an inflation target, before Chair Bernanke formally codified as an explicit Federal Reserve policy target in 2012), by the year 2000 the CPI inflation began to diverge from its 2% target and has not once reverted. At the end of 2022, CPI was more than 11% higher than it should have been had inflation been properly controlled; as of June 2023 (the most recent data point available), actual CPI was tracking almost 14% higher than where it should be given the 2% target. Note that this does not imply that the inflation rate is almost 14%, but instead illustrates the difference between how quickly the American economy has actually been growing versus the rate at which it should have been growing. This is especially concerning given that the base effects are being ignored. For instance, comparing CPI of June 2023 to CPI of June 2022 – when Russian aggression had spiked energy prices – would make this slowdown look particularly dramatic. One good print does not make a trend, and the downstream results of this can be seen with things like mortgages: FRED data show a drop in mortgage rates starting in March of 2023 (when the average mortgage rate was 6.73%), which caused much rejoicing but lasted exactly one month. The average mortgage rate in mid-July is almost 7%. Housing is only one of 8 categories in the CPI, but it’s arguably one of the categories – along with food and energy, which are normally disregarded due to their volatility (CPI with food and energy is still at about 5%) despite their essential nature to survival – that consumers feel the most. Grocery prices in the CPI remained unchanged. Unfortunately, the Fed cannot pick and choose which components of CPI to control via policy, since even if such actions were possible they would run the risk of causing widespread, unintended, detrimental effects to the economy and/or earning the ire of lawmakers who feel the need to politicize a fundamentally mathematical phenomenon. Using a scalpel – as opposed to the Fed’s broadsword – to address matters such as housing affordability is something best done by the private sector. Much of what’s keeping inflation elevated is the resilient labor market, which has seen employers increase wages and thus enabling Americans to continue spending. Eighty percent of companies, in fact, gave a raise in 2023. It’s easy to see how this can create a vicious cycle: employers give raises to keep employees, who then have more disposable income to spend, which in turn exerts upward pricing pressure. The personal savings rate has increased over 70% since July 2022 (from 2.7% to 4.6%), but if one discounts the spike in savings caused by the pandemic, personal savings are barely above the level they were in August 2009. Put simply, Americans are celebrating disinflation rather than looking at deflation. The producer price index (for goods, not services) decreased almost 5% over the past year, whereas total PPI for June 2023 remained relatively unchanged from a year ago. PPI is usually a leading indicator of CPI, but the problem is that the US is a massively service-dependent, import-dependent economy. Recent news suggests that several economies around the world – almost all of whom depended on the US economy as the “risk-free” bedrock – have been getting economically wrecked to the point of desperation and attempts to de-dollarize. These also happen to be the same economies from where we get much of our raw materials and intermediary/finished goods, and who are no longer convinced that the Almighty Dollar is a necessary part of their future. The control and stabilization of the American economy is not simply a matter of protecting our livelihood, but of national security. Tragically underreported is the unfortunate reality that consumer revolving credit has consistently increased since 2000, reaching a level of almost $1 trillion. This has been given cursory attention, but presents a potential financial time bomb once the student loan moratorium ends. Once that happens, millions of Americans are going to be financially obliterated as they transition from “living on credit cards” to “living on credit cards with even less money to pay them down.” There won’t be any stop to the debt spiral until rates start getting cut, but if Powell cuts rates too soon the resurgent inflationary spike that will ensue will make a return to normal virtually impossible without dramatic action.

We at Garrison Fathom remain pessimistic and are staying patient with our holdings and investments. Our team will continue to monitor and report.

1 Comment

|

CategoriesArchives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed