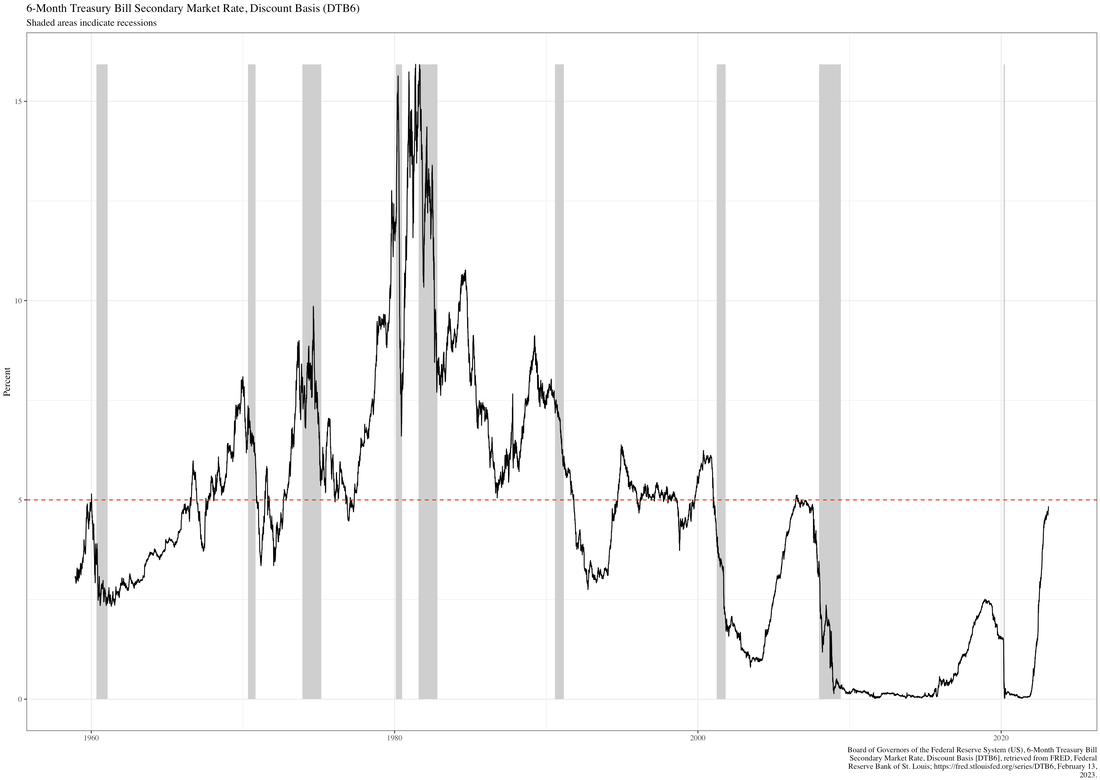

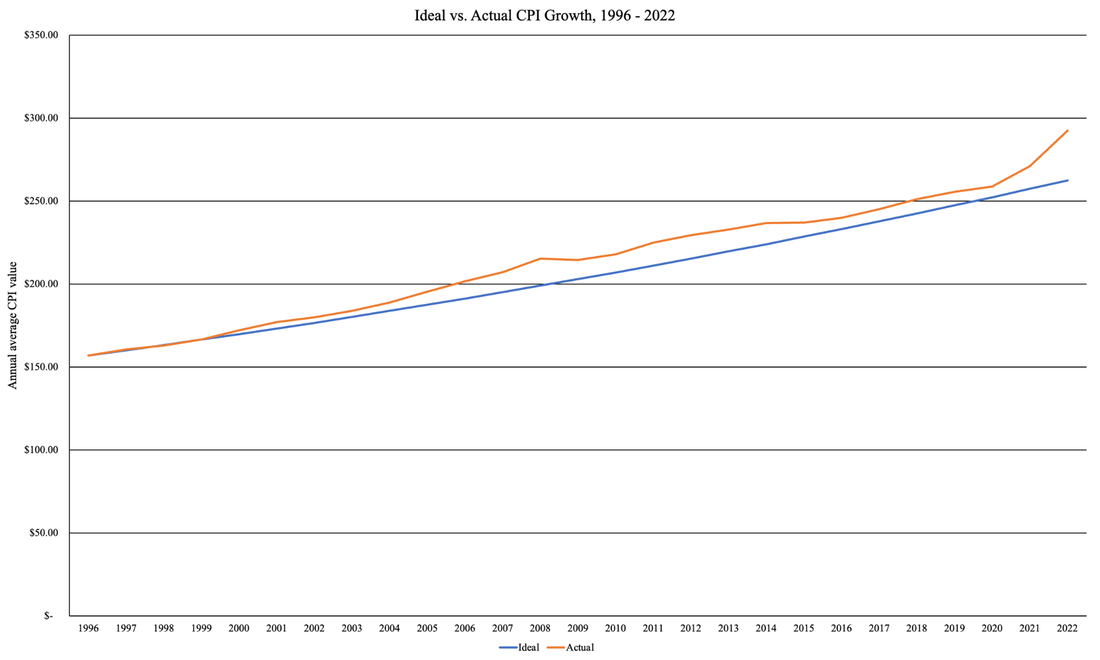

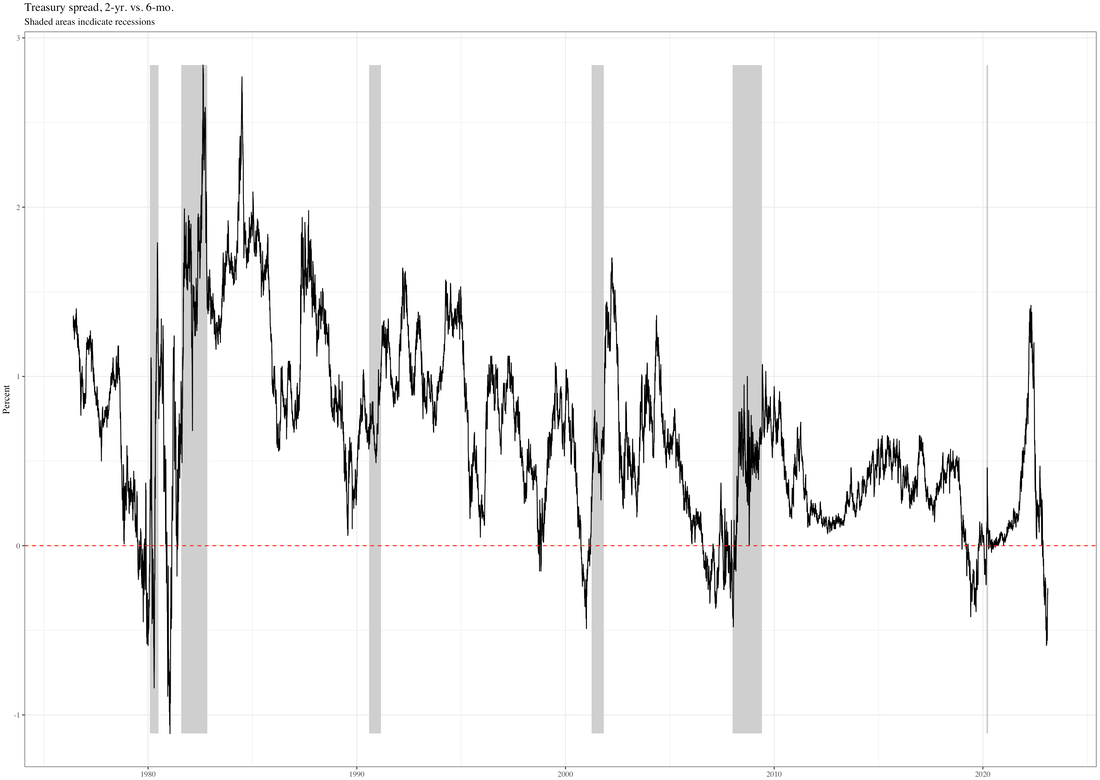

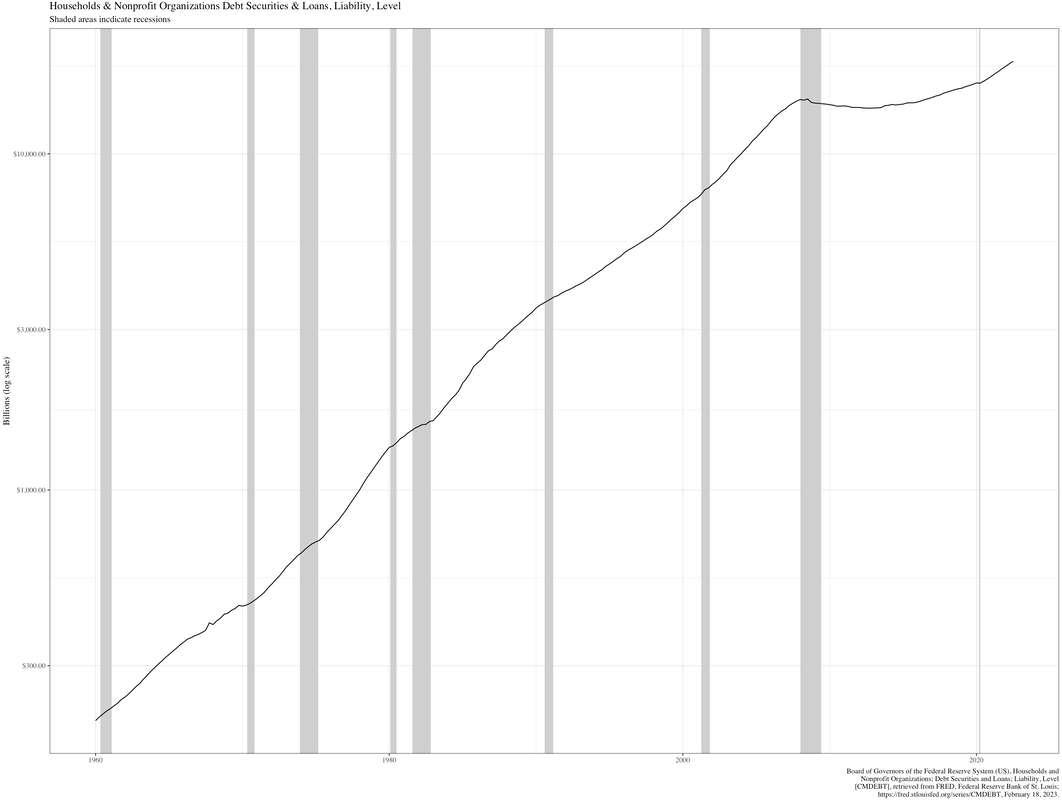

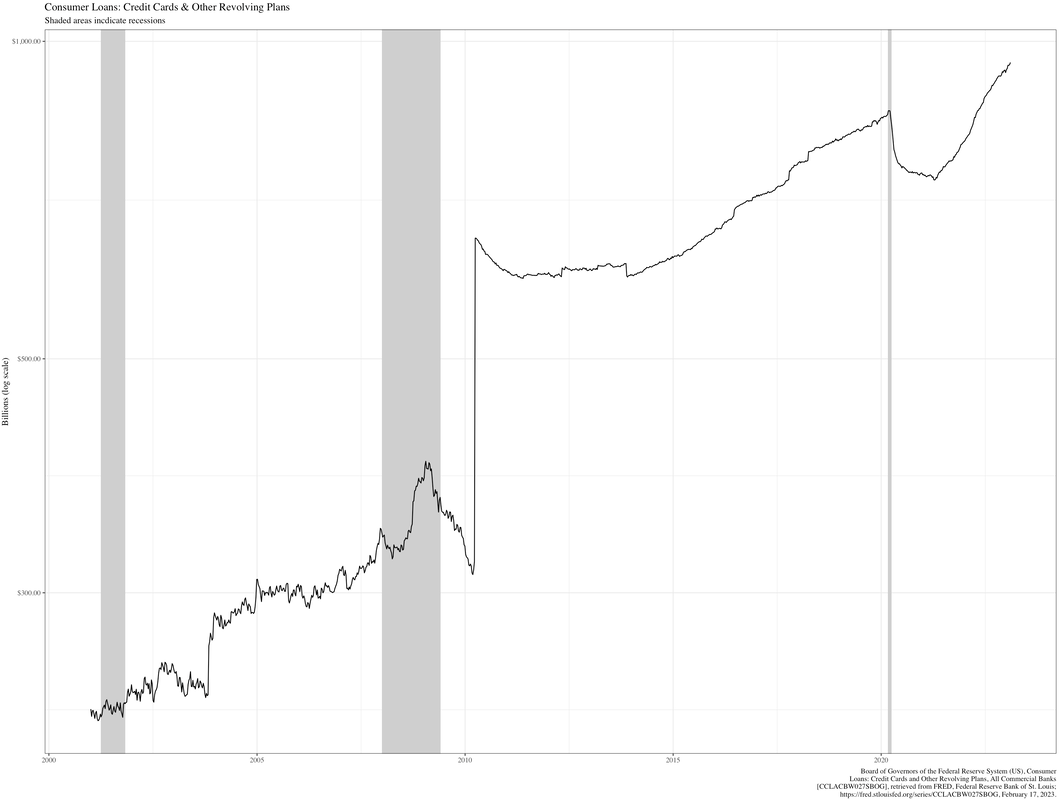

The continued abuse of our financial system is causing it to malfunction.By Willie Costa and Vinh Vuong The cracks of our financial system are beginning to show fundamental weaknesses that indicate most of what we’ve always assumed might be coming to an end. Unfortunately, this would be a failure of seismic proportions that would adversely affect the lives of hundreds of millions of Americans. We’ve never been shy about our bearishness, especially when it comes to irresponsibly tinkering with the greatest and most powerful macroeconomic machine in the history of humanity, but some items as of late beg the question of just how disconnected from reality people can be before opinion turns to delusion. Carl Quintanilla, a highly experienced and decorated journalist, recently shared a tweet that makes one wonder precisely what’s being put into the coffee over at Wells Fargo. To be clear: the bear market is not over, and there is no bull “stuck in traffic” amongst irrational P/E ratios and downgrades. The market’s exuberance over the possibility of rate cuts is like a drowning man deluding himself that splashing frantically counts as swimming and inhaling more water as a result. The Fed is nowhere close to ending their rate hikes, and yes, we are still in an inflationary cycle. Of particular concern is the behavior of the six-month Treasury, which Quintanilla helpfully points out hasn’t been this high since 2007: Of course, the picture gets more dire when one looks at the rate spread between the ten-year and two-year Treasury bonds – the oft-mentioned and occasionally much-maligned yield curve – which has reached an inversion not seen in nearly forty years: This inversion (the above graph indicates the spread between ten-year and two year T-bonds: , which is often taken as an indicator of a recession, although it seems that, historically, the rebound from an inversion correlates better with the start of a recession) is a simple barometer for the health of the economy: so long as the return of the ten-year bond exceeds that of the two-year bond, the economy is said to be in a normal working state (because investors will demand a higher rate of return for their money being invested for a longer period of time). When the yield curve inverts (i.e. investors want a return now instead of years from now), it’s usually indicative of expected tough times in the near term. Unfortunately, the 2-10 isn’t the only yield curve inverting at the moment: Yes, you have read that graph correctly: right now, the yield on the six-month Treasury exceeds that of the two-year Treasury. And, again, this phenomenon is of a magnitude not seen in forty years. At some point, the relationship between interest rates and economic cycles becomes tautological, but it’s rather staggering how often the simplest things are the hardest to accommodate. After all, “everyone knows” that rates have to hike to cool down the economy after a period of rapid inflation (say, for instance, a “hypothetical” one caused by irresponsible government spending during a pandemic and then subsequent ignoring of an increasing CPI…), yet some of the industry’s most intelligent experts not only seem surprised by the reactions of the economy, but also seem eager to paint a picture of “all is well” despite twenty-year high levels of consumer debt (and increasing rates of serious delinquency – perhaps Michael Burry has not yet left the building) and still-raging inflation. We are living in an age where eggs cost more than meat, automakers rake in profits from artificially-constrained supply causing monthly payments to soar… and of course, this causes the knock-on effect of reducing mobility options for the most economically vulnerable, who subsequently have their options for advancement reduced: climbing from poverty to the penthouse is not impossible – Chris Gardner did it – but the trip sure gets a bit easier when you have safe and reliable transportation to get you there; particularly terrifying is that more than half of our college-educated population – the very people who are supposed to be the Leaders of Tomorrow – are staking their chances of financial stability on federal debt forgiveness. The state of our economy may be politely referred to as something that is antithetical to the vision of the Founding Fathers. Of course, these are the macro movements. In the world of microeconomics, where most Americans live, things are equally dire. Aside from the aforementioned spikes in prices, total household debt stands at nearly $19 trillion. Mortgage loans considered in serious delinquency (i.e. past 90 days) – everyone’s favorite disaster from 2008 – have increased to 0.57%: low, but still double from the previous year. Not known for missing out on a great catastrophe, auto loan delinquencies and credit card have increased at twice the rate as mortgages. While the media crow about low unemployment, prices have remained stubbornly high, which has led to rate hikes that will test the ability of consumers to repay their debts. Meanwhile, consumer credit card debt is skyrocketing to levels even higher than the post-2008 spike. This shouldn’t be a surprise: higher inflation leads to higher prices, but when wages don’t rise accordingly consumers are tempted – or forced – to rely more and more on credit just to make ends meet. The only cure for this debt is either paying it off (not always likely, given our culture of “buy now, pay over the rest of your life”) or a strong and sudden contraction that forcibly reduces the aggregate debt load, usually via charge-offs, layoffs, and other hardships best avoided. Note that it’s not necessarily the scale of debt that should matter – after all, debt is one of the critical factors that help an economy expand and also (perhaps ironically) helps expand personal and corporate wealth – it’s the scale of debt given other economic factors that serve to give one pause. In this case, increasing the debt load to help fund purchases (many of which, like food and fuel, are somewhat necessary for survival…) in an already inflationary environment will create a feedback loop that only increases inflationary pressure. This is why we’ve reiterated that a soft landing is not only unlikely, but probably impossible; this is made worse by an illogical (but wholly understandable) focus on job growth numbers in an effort to distract Americans from the edge of the cliff. Some say that the Fed’s 2% inflation target is unrealistic without crashing the economy, and that the central bank should be targeting an inflation rate in the 3-5% range but refuses to do so out of fear of losing face. There may be some substance to this – the US inflation rate has been relatively constant at between 0-5% since 1960 – and the inflation rates of most first-world “benchmark” economies (e.g. Switzerland, South Korea, France, Canada, Singapore, Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) have spent happy decades remaining relatively stable within a tight oscillatory band. Yes, excursions happen and are to be expected, and the tightly-knit nature of a global economy mandates that economic turmoil eventually drags multiple nations down with it, but so long as the past twenty years of Argentina’s inflationary catastrophe of an economy can be avoided, most would consider it a victory.

But why target 2% inflation? In theory, it could be 4% or 8%, but the key would be consensus. A 2% inflation target has not only been the US policy since Ben Bernanke, but has been the official or de facto target of the European Central Bank and similar institutions since the 1990s. Changing our inflation target would be meaningless without cooperation from other central banks, and a good inflation target will keep economies stable without unfairly penalizing innovation. The delicate balancing act is that central banks need margin to cut inflation without collapsing the economy, causing a deflationary spiral and subjecting the US to japanification – the slow economic death that stems from consumers refusing to consume. The closest we’ve come to this since the Great Depression was the 2008 collapse, and that was likely quite enough economic “excitement” for most people. The simple fact is that people forget – or have been made to forget – that the economy is supposed to work for them and not the other way around. But there exists a solution that will truly evolve an industry that hasn’t seen much change in the actual products for centuries. Yes, there have been advancements in the technological side of finance, almost all of which have been revolutionary, but the core products have not changed much outside of index funds thanks to Vanguard and the Bogleheads. We at Garrison Fathom are working on this solution as you read this. Our products will drive responsible capitalism while giving people something they could never have imagined: the chance to use their debt to create generational wealth. Lending, investment banking, and how we live and retire will change forever. Stay tuned and subscribe for updates by emailing [email protected].

4 Comments

|

CategoriesArchives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed