|

The concept of a bank, as a formal financial institution, has existed since at least 1472. The first public securities market was opened in 1611. You’d think we as a society would’ve gotten things right by now, but the recent collapse of Silicon Valley Bank proves otherwise. Bank failures in and of themselves are nothing new – over 9,000 failed just during the Great Depression (and without the benefit of FDIC insurance… ouch), and from 2009-2023 there were 512 bank failures in the US alone. In fact, bank failures (yes, in the US) are so common that years like 2005, 2006, 2018, 2021, and 2022 – when there were zero bank failures – are the exception. Even since the start of the coronavirus pandemic and prior to the collapse of SVB, only three banks in the US failed, and all three had experienced previous financial problems. SVB’s collapse was actually the second-largest in recent US history, right behind the fall of Washington Mutual during the 2008 crisis. Banking basicsSVB experienced a good old-fashioned bank run, plain and simple. Until the panic started and depositors tried to pull their money out – which escalated to the point that police were called to handle the crowd – the bank was nowhere close to insolvency. But when some of the Valley’s “whales” (including one investor whose portfolio companies purportedly pulled a total of $1.5 billion from the bank) began heading for the exits, this created the same self-fulfilling prophecy that financial institutions have feared for centuries. So why the panic? Part of it is human nature, and another part is mathematics. Banks aren’t typically in the business of holding enormous stacks of cash for no reason: they must make money to pay employees, etc., just like any other business. They do this by giving out loans and collecting interest. Typically, a bank will only keep enough cash on hand to meet the higher of two criteria:

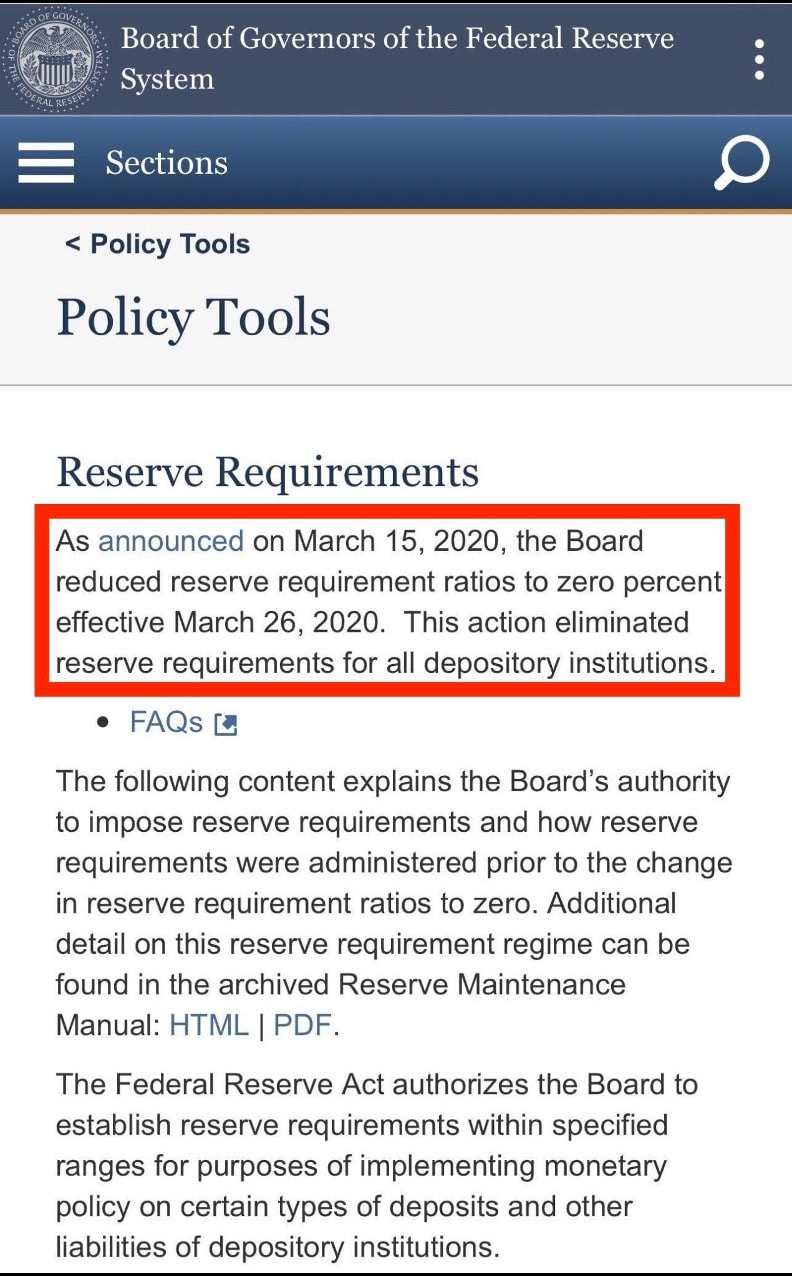

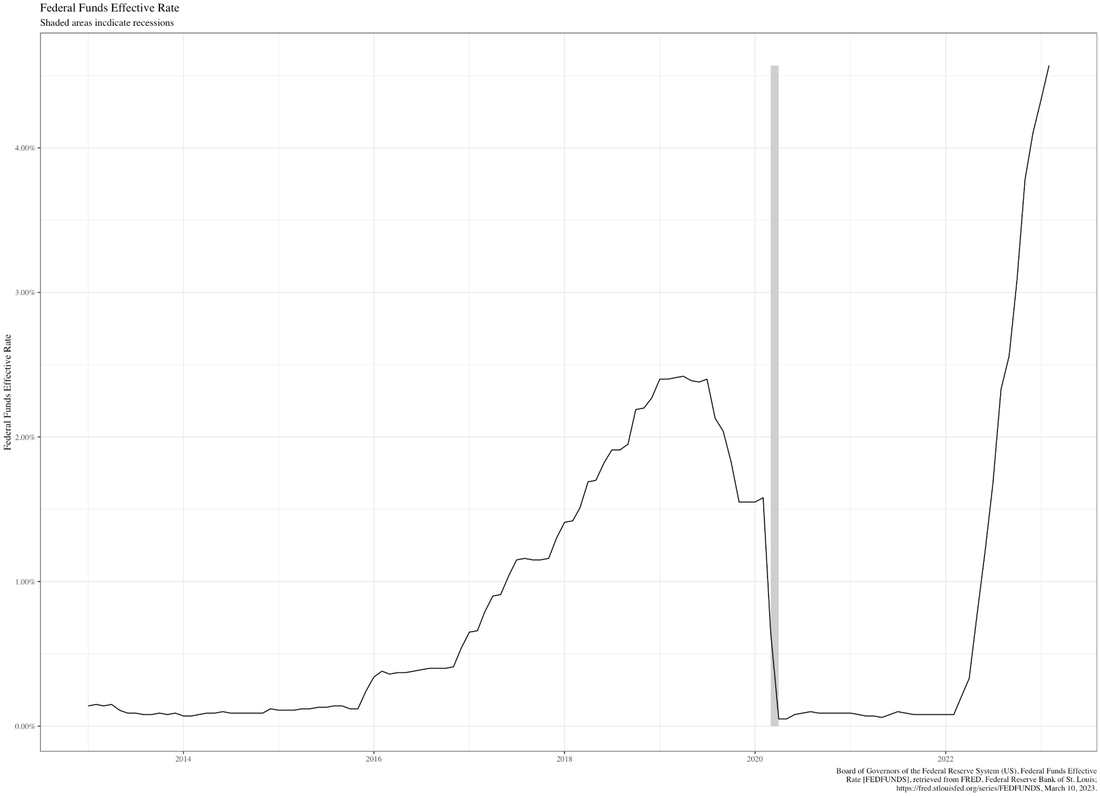

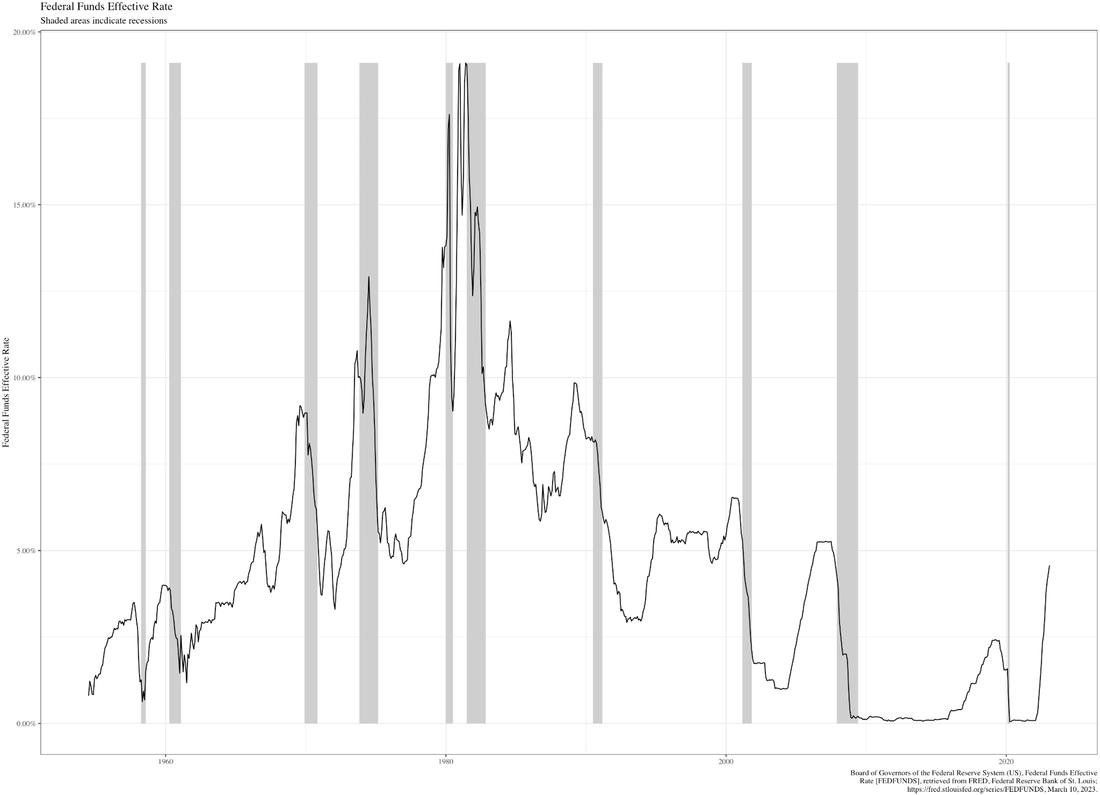

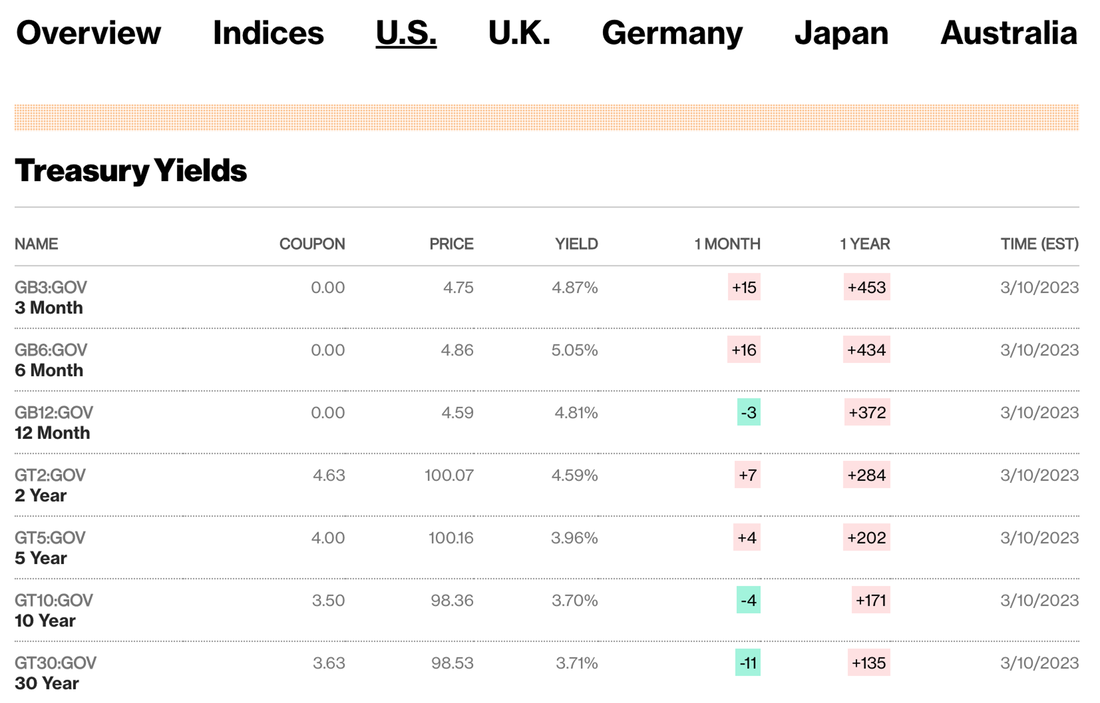

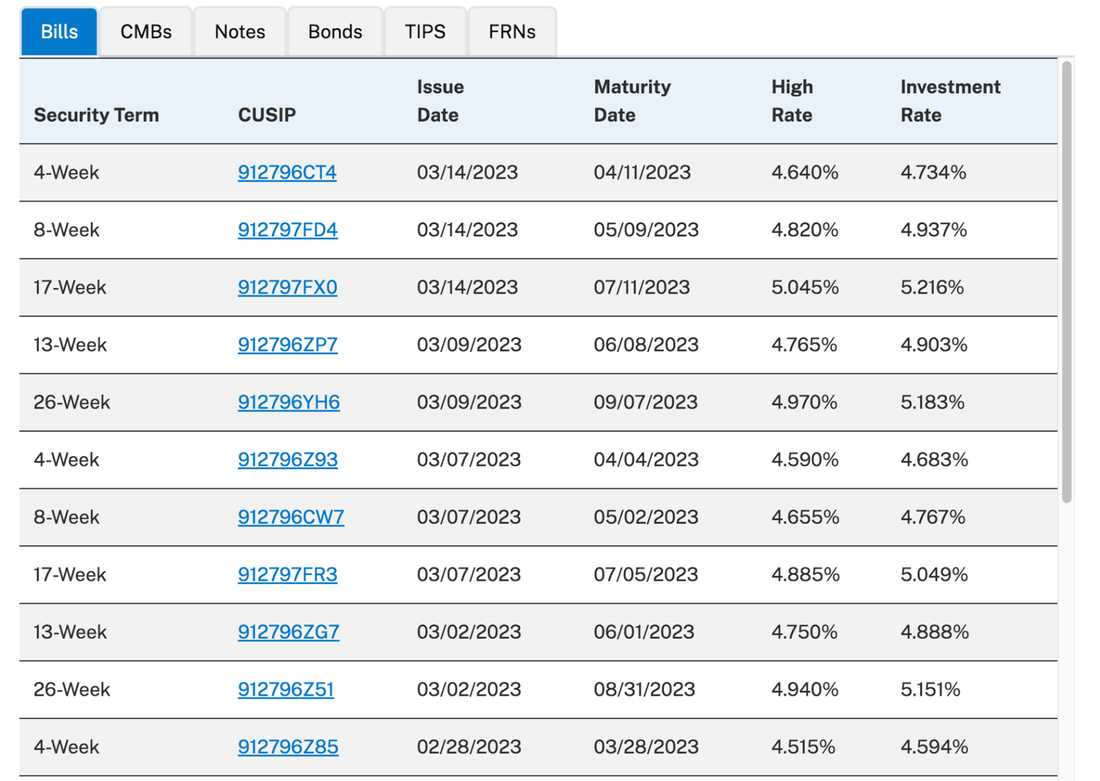

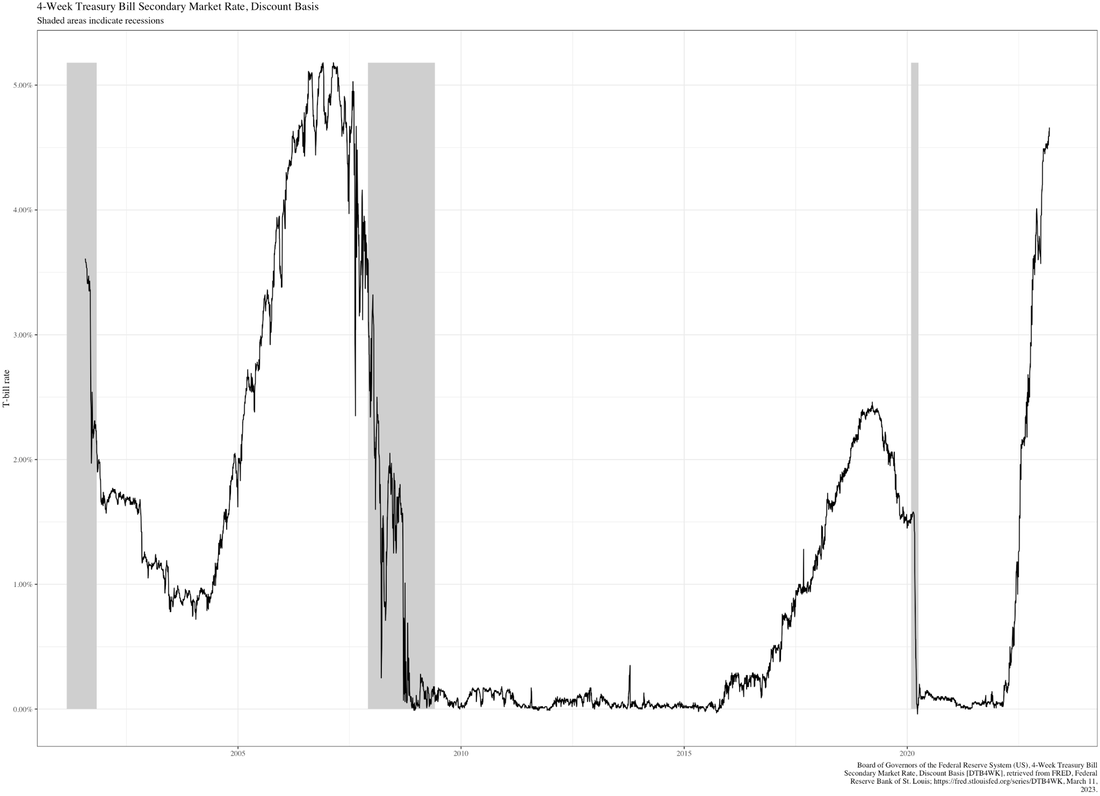

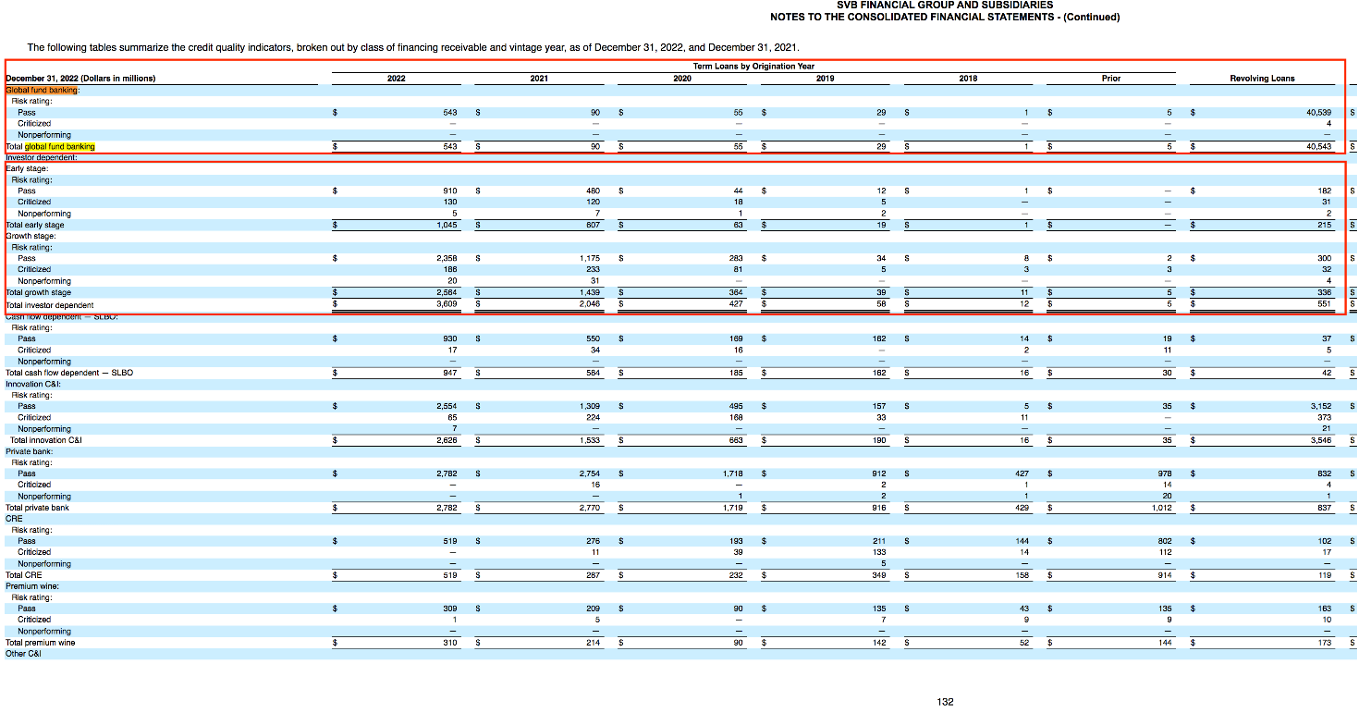

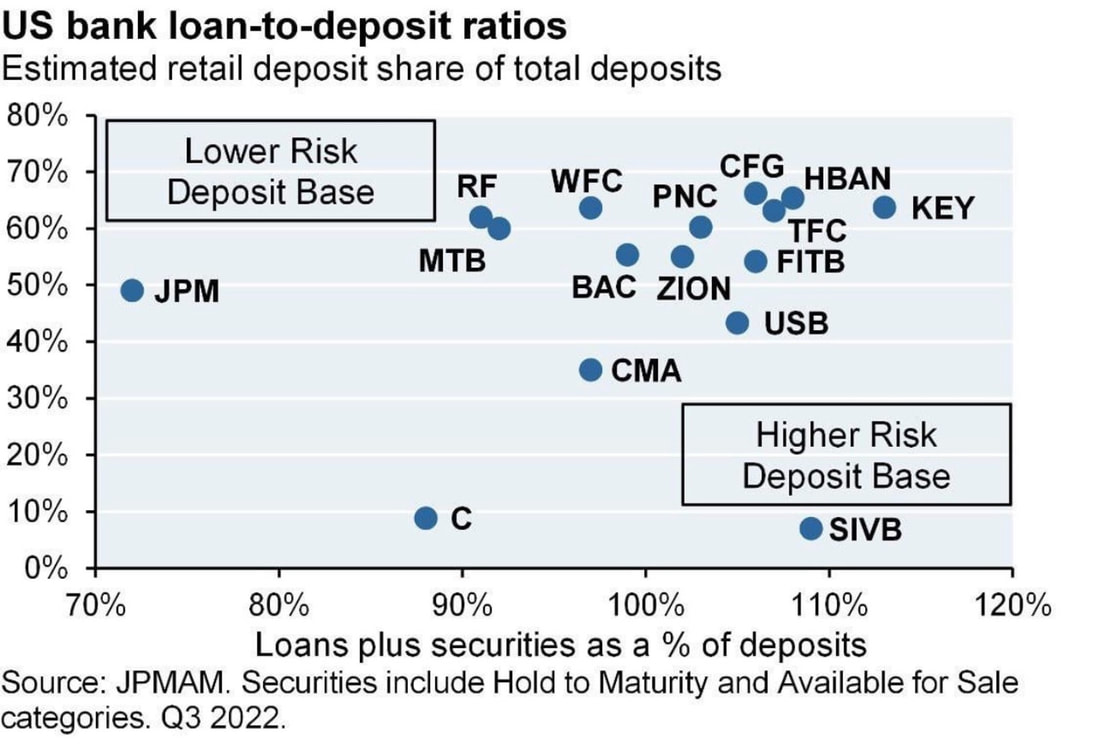

Of course, banks would prefer to only keep the amount of money in reserve that’s necessary to meet operational requirements: while the Federal Reserve began paying interest on deposits in 2008 (known as the interest on reserve balances, or IORB, which reached a whopping 0.10% in 2022… about as bad as the rates offered to savings account customers), banks can be much more profitable by making loans and collecting interest. These capital requirements have changed over time, and despite arguments from the banking industry that higher capital requirements harms economic growth (by forcing banks to reduce lending or increase the cost of capital), the reality is that both capital requirements and lending have increased between 2013 (when higher reserve ratio requirements began taking effect) and 2020. Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve decided to set the reserve requirement to zero: This period of zero reserves was short-lived, and by February of 2023 the reserve requirement had increased to a much more conservative… 1.27%. Meaning that almost 99% of a bank’s deposits were “out in the wild,” as it were, providing capital to loan customers, rather than sitting in the vault. Assumptions that this is not much to fall back on in tough times are both chilling and correct. So if capital requirements aren’t directly impacting lending activity, what does? Quite simply, it’s interest: loans are nothing more than the result of a bank calculating opportunity cost – if they can make more money lending to you (yes, factoring in credit risk, probability of default, loss given default, time value of money, etc.; they’re businesses, not charities), as opposed to holding reserves and collecting IORB, then they lend to you. But this mindset in many ways ties the hands of banks to the broader economic climate. Why did capital requirements and lending both increase between 2013 and 2020? Well, for starters the interest rate environment was significantly different than today: In fact, until the current economic turmoil, the Federal rate had been nearly zero for years, and even today, with all the crowing about the “brutally high” interest rate environment, it’s readily apparent that neither Wall Street nor Capitol Hill are in any danger of looking at history with even an ounce of critical thought: This interest rate environment provides a critical insight into why SVB collapsed. The bottom line is that anyone can make money when times are good – that is, in fact, why good times inevitably lead to hard ones – but it’s only when the markets turn that sanity is put on hold and proper financial strategy shines. Anatomy of a collapse: a semi-deep diveThe bank run on SVB illustrates one of the key flaws inherent in much of the financial system (which we’ve covered before): it depends almost entirely on the origination, packaging, and reselling of debt, which in turn locks you to the whims of interest rates. But we're seeing what happens when the Fed continues to hike interest rates – to the point that a 2-year Treasury is exceeding 5%, which in 'normal' times is the cost of capital of most firms – and banks like SVB are forced to sell their bond portfolios at a loss just to have liquidity. SVB’s collapse is directly traceable to an unforced, unnecessary, and self-inflicted error: that of management choosing to sell $21 billion worth of bonds at a $1.8 billion loss. Why? Because those bonds were yielding less than 2% at a time when buying Treasurys could yield more than double that. The bank’s bond portfolio was underperforming relative to peers (on paper, anyway), and SVB were faced with the threat of Moody’s downgrading its rating (of course, the true value of a high rating from a credit agency is itself suspect). With the help of Goldman Sachs, who may have been searching for some way to draw attention from an executive allegedly participating in one of the biggest heists in history, SVB chose to raise new equity capital and sell a convertible bond to the public. The core issue is one other banks would be wise to be aware of: SVB had invested customer deposits in low-yield bonds that were on the books on a hold-to-maturity basis. This means that they didn’t have to mark those bonds to market until they were sold. So long as the bank didn’t sell those bonds, there was no problem: the balance sheet, although distorted, would have remained stable. It’s only when the bank sells these bonds to meet withdrawal requests that things become painful. This entire ordeal will undoubtedly spawn a detailed and protracted postmortem that will lead to much sabre-rattling in Washington – all sound and fury, signifying nothing. Why would SVB do something that appears so suicidal in hindsight? Well, to ease investor sentiment, of course. Whether the fire sale of the bonds or the fundraising was the first to trigger panic is unclear (and may never be entirely without argument), as is whether either action was made under duress. What is known is that the actions spooked the bank’s clientele, many of whom are extremely educated and financially literate, and who in response began pulling their deposits en masse. Remember the reserve ratio? In the United States, it’s never been 100% (nor would there be any logic in making it that high), which means that no bank is required to hold more than a small amount of customer deposits at any given point in time. But while the SVB collapse may be an outlier (even in Silicon Valley, where failure is itself seen as a merit), the fallout may not be known for a while yet: SVB wasn’t the proverbial Nowhereville Savings & Loans – it didn’t hold a lot of retail deposits like the Chase branch down the street might – but banking crises are like cancer: the death of one bank can affect the likelihood of others failing, depending on which bank is exposed to what types of risks caused by the failing institution. Why not [...]?The first question on many people’s minds is likely: where’s the FDIC in all of this? Not only was SVB allowed to fail (you could argue that it was forced to fail, since DFPI decided to close it down), but isn’t that also guaranteeing that everyone’s accounts were also allowed to fail? Not necessarily. SVB was FDIC-insured, which means those deposits are guaranteed… unless they exceed the limits imposed by the FDIC, because the FDIC can’t insure all deposits for all customers at all banks. FDIC doesn’t just hand out insurance on a whim: not only must insured banks meet the standards set forth by FDIC and pass periodic examinations by the FDIC’s Financial Institution Specialists (“fizzes”), but they must also pay a premium on their deposits. Yes, banks must pay for FDIC insurance, just like one might have to pay for car insurance, because the FDIC actually receives zero money from Congress – in one of the rare examples of governmental efficiency, the FDIC is entirely self-sufficient, with its budget supplied by the premia paid by member banks. Increasing deposit insurance by default means increasing the premia paid by banks. Recall that banks make their money on spread: they charge a higher rate on loans (i.e. money they receive in the form of profit) than they pay out (to holders of savings accounts, bank products like CDs, and to the FDIC). The real time bomb might be that the FDIC insures trillions of dollars on an operating budget about 400x smaller than that, and a net income that is still dwarfed by the amount insured. If you increase the operating cost of a bank, you’re forcing it to charge a higher interest rate on its loans. Do you think the current interest rate environment is too damn high? Imagine that being permanent. “But why don’t banks just decide to make less money? It would be better for the economy!” Why don’t you decide to voluntarily take a pay cut? It would be better for the company, wouldn’t it? The typical net profit for a bank – at least one that isn’t a financial superpower that can enjoy massive economies of scale – is about 10-15%. That’s certainly better than some industries (education: 2.92%; air transport: -1.71%). But a bank is just like any other business in that it must set aside funds for rainy days… such as those we’re facing right now. What was management thinking?Honestly, we might never know, and it’s unclear if even SVB’s managers understood the consequences of their decisions. To be honest, there’s already a lot of pressure to transfer cash to short-term Treasury bills and bonds, especially considering that the yield on a 3-month T-bill is nearly 5%: This isn’t shocking: when the Fed raises rates, Treasury yields rise. Recall that a Treasury instrument is “as good as cash” (it’s considered a cash equivalent). Even the rates on the shorter-duration T-bills is nearly the same as the historical market risk premium: For comparison, the only time this millennium that the four-week bill has been higher than the current rate was in 2007: This shouldn’t surprise those who read this post: the Fed took a lackadaisical approach to tackling the “transitory” inflation problem caused by massive coronavirus relief spending; and contrary to Chair Powell getting called out for rate hikes, which are one of the Fed’s only tools for fighting inflation, the massive injection of capital into the economy was a measure that enjoyed bipartisan support. Powell is neither saint nor sinner in this regard: central banks are always behind the curve when it comes to policy lag by simple dint of humanity’s complete lack of clairvoyance, and the effects of a systemic shock are impossible to immediately recognize, and are also impossible to immediately fix. Notice that no real-world economic data are as smooth as those found in textbooks: in what is perhaps the understatement of the century, we must reiterate that economies are far too large and complex to constantly “fiddle the knobs” to affect uncertain effects on an unknowable future. Hindsight is both 20/20 and occasionally overrated: in a certain perverse way, Powell’s initial lack of action may have been necessary – markets require stability to function, and repeated fiddling can cause more harm than good. That said, such an enormous spike in money supply probably should’ve raised a few more eyebrows… Should this have been expected?SVB’s managers (who may or may not all now be out of a job) invested short-term deposits in long-term assets. That’s the long and short of it. But anyone who’s been awake the past couple of years should have suspected that the massive pandemic spending would fuel inflation and thus necessitate rate hikes. And contrary to what many are saying, SVB was not a bank run by gambling-addicted degenerates: examining its most recent 10K shows that the bank actually exceeded Basel III requirements for CET 1. US banks under Basel III have been de-risking for years, and SVB was no different. According to SVB’s SEC filings, yes, SVB did in fact participate in This is hardly the hallmark of a cabal of degenerate gamblers out to ruin innocent investors and depositors for personal gain. Global Fund banking is actually very safe: it’s mostly funding venture capitalists to make transactions while they await a capital call. In other words, if a venture capitalist wants to fund a company but they have to wait (one week, one month, two months, whatever) for drawing down from their LPs (the people/institutions that actually provide the venture capitalist with money), then the VC will ask for a line of credit for this purpose. Venture and private equity funding is contracted, and historically the default rate of venture funds themselves is very low – contrary to popular belief and Silicon Valley’s penchant for high-risk endeavors, VCs are not stupid, and they tend to prefer to not lose money. These VCs were over-collateralized through the value of their homes, typically on the order of 150% of the loan value. Does this seem risky? Maybe to some, but this is Silicon Valley: home prices are relatively stable, even during recessions. In fact, for the past 20+ years the price of homes within Silicon Valley have mostly stayed within a band on +2%/–1%, with only occasional excursions beyond that: The investor-dependent portion of SVB can also have been considered safe, as these loans were basically bridge financing for when a round had already closed (viz. capital already committed) and there was a lag between when papers were signed and when money was transferred. In other words, SVB was a bank holding a large portion of its book in government paper and the rest in pretty safe lending. The “speculative” portion of its book was miniscule. This is in wild contrast with Silvergate, whose implosion was driven by a pivot into cryptocurrencies and was, arguably, entirely deserved. But a conservative book does not equal conservative management, as we have all witnessed. SVB catered to a very unique clientele that had high withdrawal needs and should have focused on holding more shorter-term securities. Yes, “woulda-coulda-shoulda,” but when this clientele requirement is literally part of your business model, management decisions should be made to accommodate: barbells aren’t just for the gym, and ladders aren’t just what you find at the hardware store. Long-dated bonds are not cash equivalents unless we’re in a declining-rate environment, which careful research (called “Googling”) will reveal has not been the case for years. In a rising-rate environment, long-dated bonds are as liquid as solid rock, turning what is normally an investment opportunity into a very real, very devastating loss. In short, SVB’s balance sheet grew massively over the past five years. Most of this money was used to acquire long-dated bonds to serve a clientele that required very immediate access to capital. Rising rates forced SVB to try and acquire capital, which it failed to do before the information became public. The subsequent run rang the death knell. The Fed only built SVB’s coffin – poor management is what shoved the bank into it, nailed it shut, and then encased it in cement. Frankly, the level of incompetence shown by SVB management is staggering, especially for a bank whose CEO literally served on the Board of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. The fact that SVB execs sold over $4 million just a couple of weeks before the bank collapsed, even if found to be purely coincidental, is not a good look. How wide will this spread?Duration mismatches in book value and mark-to-market value for held-to-maturity investments are expected: the price today (when you book) is not going to be the same as the price tomorrow (when you sell) because what drives the sell value of a bond (interest rate) is going to change. Rates go up, value goes down – that’s Finance 101. Average maturity in SVB’s book was about six years: when bonds are sold, they’re marked to market, and a sharp drop in book value (due to rising rates) can easily wipe out a large portion of a bank’s value. As was the case with SVB. The real question is: who will actually get hit the hardest, and what will be the follow-on effects? SVB was not a stupid bank run by stupid people – if anything, it was very cautious – but no matter how conservative you are, you’re never going to survive a bank run unless you keep 100% of deposits on hand, 100% of the time. In that case, you’re not a bank, but a bank-shaped economic black hole that’s doing nothing but losing money. That would be irresponsible; making loans and following FDIC and Basel standards is not. The real wild card in this scenario is the fact that a large portion of the money held was going to startups, who are themselves extremely funding-dependent. When a major fund pulls out all of its money from SVB, as Founders Fund did, a run is inevitable. As an interesting (if morbid) historical footnote, SVB may have been the first victim of a social media-fueled bank run. The pain is going to start when startups can’t meet payroll and have to lay off workers – something which the larger companies have been doing for months. It is absolutely not a worker’s market in the Bay, and may not be for some while. If most of SVB’s accounts were above the FDIC insurance limit – and it seems that most were – then over the next couple of weeks to months (maybe years?) depositors might get back 90 cents on the dollar, when it’s all said and done. That’s better than getting nothing back, but just as SVB’s bonds were mismatched to requirements, so too are the FDIC’s machinations to resolve these issues: you need money today, but you’ll get paid next year. That’s not great. Also not great is the amount of deposits, as a percentage of SVB’s total deposits, that were even insurable by FDIC: SVB had very few retail deposits (the money of “average Americans”) as a percentage of its total deposits, but the deposits it did hold (by definition, non-retail, aka commercial and high-net worth entities) was therefore correspondingly high – and therefore of higher risk. JP Morgan may actually come out of this unfolding debacle (and subsequent bank collapses are sure to follow) as the only real winner. Some of the Valley’s darlings are probably going to be hit the hardest: Roku, for instance, held about $487 million in SVB, or about 26% of its cash; other companies such as Etsy and Rocketlab have also had their cash exposed due to SVB’s collapse. Fears of contagion are already global, and it’s unlikely that SVB will receive any help – in fact, executives in the Valley have already heard that they will receive no bailout from the federal government unless there’s clear evidence of widespread bank runs. And there is evidence of such a threat: see, it wasn’t just Silicon Valley startups that had their money in SVB: the bank had branches in China, Denmark, Israel, Sweden. In the UK, startups were canvassed to ascertain their exposure to SVB’s collapse, burn rate, and access to cash; in Canada, SVB had over $400 million in secured loans (double from the previous year); Shopify, HLS Therapeutics, and AcuityAds are exposed to SVB’s collapse (AcuityAds alone had more than 90% of its cash in SVB). Smaller banks like First Republic, The federal government, to its credit, is aware of the importance of preventing a cascading collapse of financial institutions. As such, they’ve stated that they’re easing the terms for accessing the discount window for SVB clientele. There’s even talk of federally guaranteed all deposits at all banks, which is rather interesting since over $13 trillion is held in “just” the largest banks but the current balance of the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund is only $128 billion. By comparison, MIT estimates that the entire cost of the 2008 bailout was a “mere” $498 billion. Of course, the Fed could simply print more money, but that will create an entirely new series of problems. The larger, “systemically important” banks can likely absorb the shock if the bank runs cascade, but the smaller locals and regionals won’t. The current administration’s war cries of a populist revolution will fall flat once the larger behemoths step in to provide banking services to millions of Americans who might quite literally be left without any other choice. Regardless of the fact that the Deposit Insurance Fund cannot come anywhere close to covering all assets held by banks, the contemporary philosophy seems to perpetually orbit one answer: SPEND. We’ve seen what that has done to inflation. The likely cash crunch that many companies will experience will probably lead to mass layoffs, which obviously spikes unemployment and reduces spending, putting recessionary pressures on the economy. Unfortunately, since the smaller banks will die first, and since those banks are located throughout the country, this scenario may see layoffs occurring across the country more or less simultaneously, rather than in waves (in either the numerical or geographic sense). This will force the Fed to slash interest rates to jump-start the economy out of the recessionary spiral that these mass layoffs will create. But wouldn’t inflation still be high? Of course it would be, and what the Fed needs to do to fight inflation (raise rates) is the exact opposite of what it needs to do to ease recessionary trends. We were called “alarmist” when we said the US was headed toward stagflation, a term that most economists find so filthy and utterly detestable that for decades it was decried as impossible. Welcome to economic hell. Why is this political?The short answer is because everything has to be made political one way or the other. Politics exacerbates economic woes, but we as a country can’t seem to kick the habit. There’s plenty of argument to be made that the FDIC and OCC are somehow partially to blame for the SVB collapse, but in our experience the government only sets the standards that banks must follow – they’re not actively involved in the strategic or operational management of them. That said, we’re facing the very real possibility that tens of thousands of the country’s youngest and brightest workers, many of whom are responsible for the trillions of GDP that are directly traceable to high-knowledge professions (e.g. tech, biopharma, engineering, science) are going to find themselves out of work. That alone would make it a political issue, and the risk of industry consolidation and increased risk to the larger banks makes it moreso. The government’s response to the SVB collapse will likely increase the concentration of power within the banking industry, ironically reinforcing an oligopoly that was itself decried as being dangerous to the average American. The other option would be to turn the systemically-important banks into government-sponsored entities, like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (or the eleven Federal Home Loan Banks, the National Veteran Business Development Corporation, or the SLM Corporation [“Sallie May”]). There’s some precedent for this – FCBanks and Farmer Mac are both GSEs – but one does not have to stray far from the political center to realize that heavy government involvement within the broader financial industry will likely choke off much of the quality of life that most Americans have come to enjoy since the end of the Volcker era. Is there a better way?Our frustration with the current financial system mirrors that of many Americans, and the conventional banking system is too dependent on interest rates to sufficiently withstand economic turmoil. We must reiterate that the only way to truly build wealth is through investing (which, yes, includes positions in bonds when rates are high), and the sad reality is that most Americans have been unable to participate in this opportunity. In short:

Meanwhile, the Warren Buffet School of Investing – to focus solely on companies with strong economic moats and sound management – has once again proven its worth, which is why our Garrison portfolio was up 4.46% despite 2022 being one of the worst years for the S&P 500 in its entire history, and with a turbulent Q1 thus far in 2023, we're up 12.23% YTD. In comparison, S&P 500: +2% YTD, Dow: +1.49% YTD, and NASDAQ: +2.32% YTD. How does this benefit the average American? We're launching our new company, FinancX, which will become the new standard for finance. Our first product (a first of its kind) will be a hybrid lending model which means you don’t have to invest or pay interest, because we’ll do it for you. With our structure, the market performance of the portfolio dominates fluctuations in the interest rate environment: a fixed portion of every monthly payment is applied to a loan’s principal, and a fixed portion is invested in a diversified portfolio that we manage for you. And the portfolio is called “Garrison” for a reason: a garrison is a military contingent assigned to defend an area – in this case, we’re using our portfolio to guard your wealth. Signups are available (non-binding) to learn more and for you to be one of the first to join the new era of finance that will finally bring responsible capitalism. We already have $25M of soft commitments in just two-weeks. Learn more here.

0 Comments

|

CategoriesArchives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed