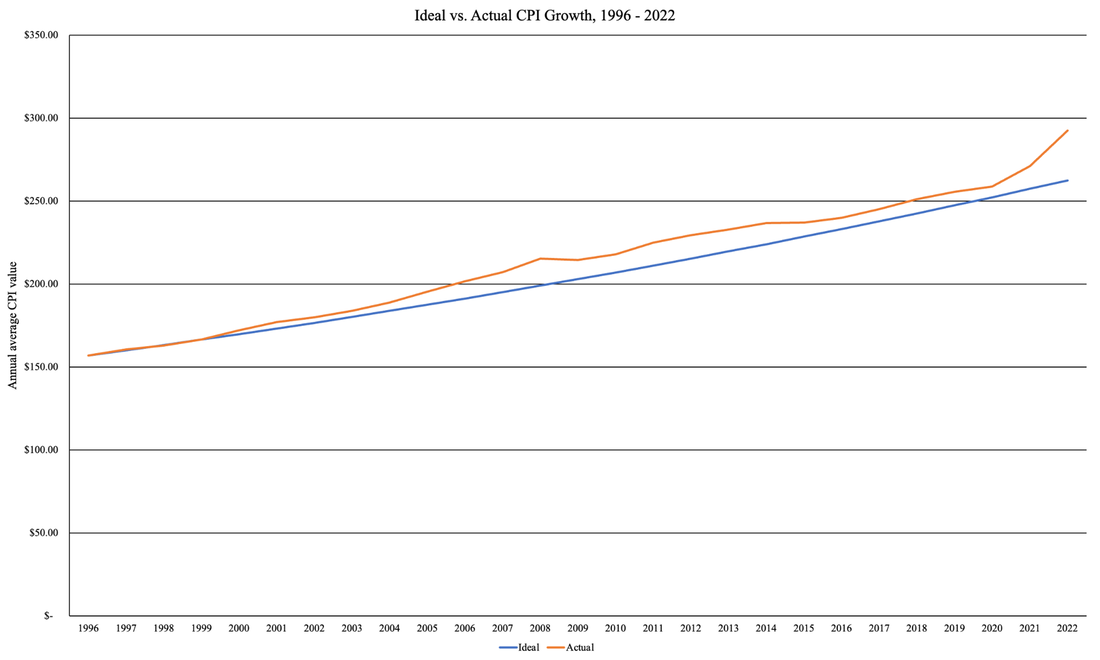

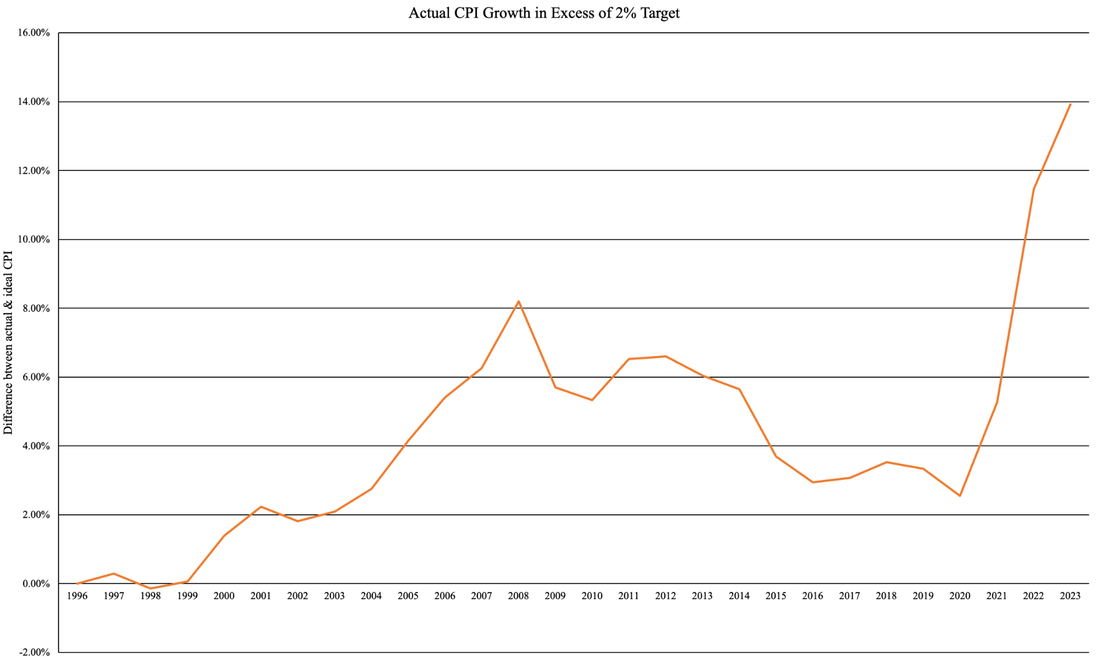

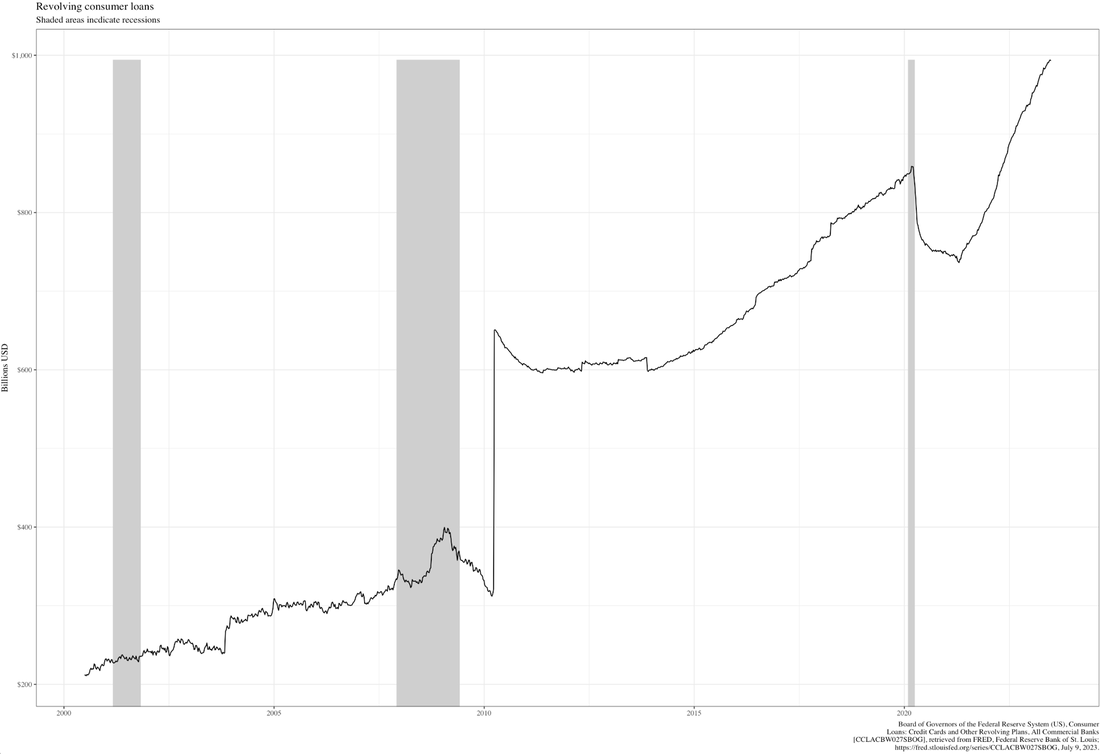

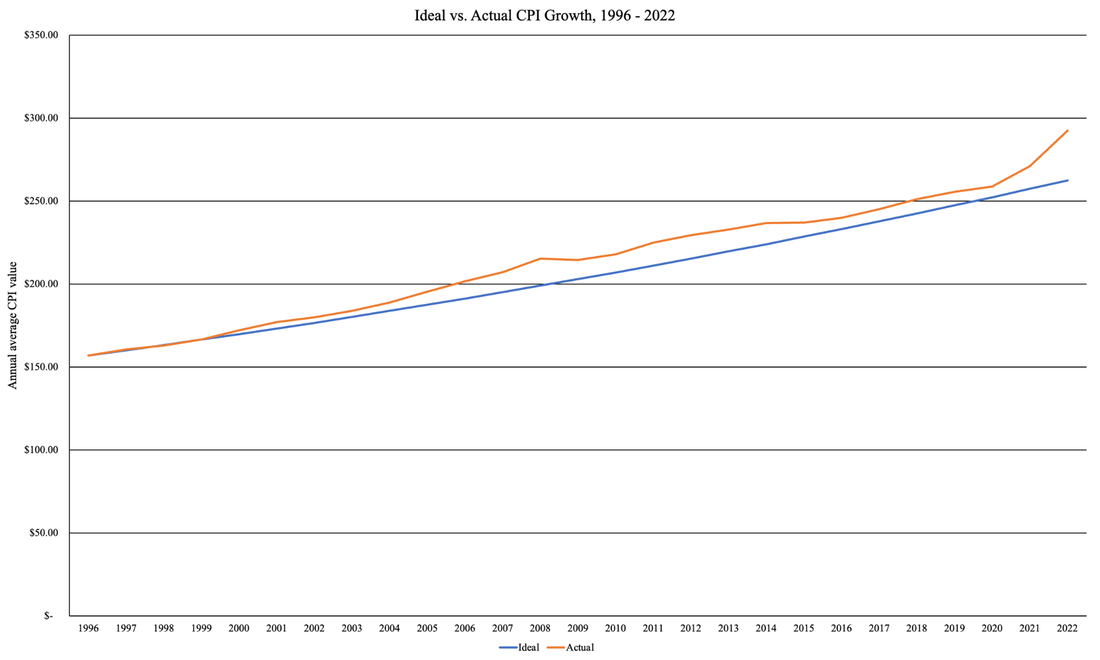

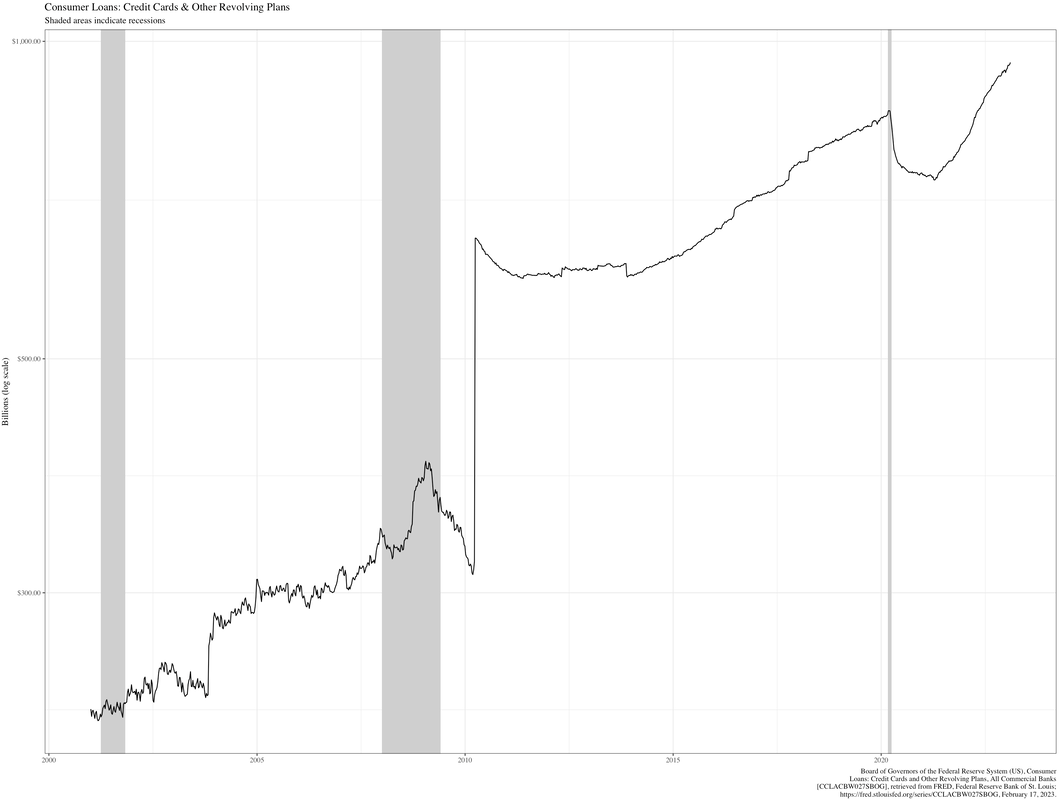

Faulty conclusions drawn from sparse data lead to a false sense of securityBy Willie Costa & Vinh Vuong The most recent numbers show that inflation slid below a two-year low, but hope that this signals the end of inflation are misplaced and completely inconsistent with reality. CPI inflation is now one-third of what it was last year, and in no way does this mean that the fight against pricing pressure is over. Both markets and economists are calling for the end of rate hikes (although the FOMC will still likely hike at its July 25-26 meeting), with short-term Treasury yields dropping, stocks rising, and the dollar falling to its lowest level in more than a year. Undoubtedly, inflation remains above the Fed’s 2% target; unfortunately, accomplishing this last bit might be the most difficult, and Americans are still feeling with every transaction. Historical data suggest that this pain is unlikely to end anytime soon: in fact, if one looks at the actual growth of CPI since the Fed began using its 2% annual inflation target in 1996 (a target that several central banks – including the Bank of Canada, Riksbank, the Bank of Japan, and the European Central Bank – all use as an inflation target, before Chair Bernanke formally codified as an explicit Federal Reserve policy target in 2012), by the year 2000 the CPI inflation began to diverge from its 2% target and has not once reverted. At the end of 2022, CPI was more than 11% higher than it should have been had inflation been properly controlled; as of June 2023 (the most recent data point available), actual CPI was tracking almost 14% higher than where it should be given the 2% target. Note that this does not imply that the inflation rate is almost 14%, but instead illustrates the difference between how quickly the American economy has actually been growing versus the rate at which it should have been growing. This is especially concerning given that the base effects are being ignored. For instance, comparing CPI of June 2023 to CPI of June 2022 – when Russian aggression had spiked energy prices – would make this slowdown look particularly dramatic. One good print does not make a trend, and the downstream results of this can be seen with things like mortgages: FRED data show a drop in mortgage rates starting in March of 2023 (when the average mortgage rate was 6.73%), which caused much rejoicing but lasted exactly one month. The average mortgage rate in mid-July is almost 7%. Housing is only one of 8 categories in the CPI, but it’s arguably one of the categories – along with food and energy, which are normally disregarded due to their volatility (CPI with food and energy is still at about 5%) despite their essential nature to survival – that consumers feel the most. Grocery prices in the CPI remained unchanged. Unfortunately, the Fed cannot pick and choose which components of CPI to control via policy, since even if such actions were possible they would run the risk of causing widespread, unintended, detrimental effects to the economy and/or earning the ire of lawmakers who feel the need to politicize a fundamentally mathematical phenomenon. Using a scalpel – as opposed to the Fed’s broadsword – to address matters such as housing affordability is something best done by the private sector. Much of what’s keeping inflation elevated is the resilient labor market, which has seen employers increase wages and thus enabling Americans to continue spending. Eighty percent of companies, in fact, gave a raise in 2023. It’s easy to see how this can create a vicious cycle: employers give raises to keep employees, who then have more disposable income to spend, which in turn exerts upward pricing pressure. The personal savings rate has increased over 70% since July 2022 (from 2.7% to 4.6%), but if one discounts the spike in savings caused by the pandemic, personal savings are barely above the level they were in August 2009. Put simply, Americans are celebrating disinflation rather than looking at deflation. The producer price index (for goods, not services) decreased almost 5% over the past year, whereas total PPI for June 2023 remained relatively unchanged from a year ago. PPI is usually a leading indicator of CPI, but the problem is that the US is a massively service-dependent, import-dependent economy. Recent news suggests that several economies around the world – almost all of whom depended on the US economy as the “risk-free” bedrock – have been getting economically wrecked to the point of desperation and attempts to de-dollarize. These also happen to be the same economies from where we get much of our raw materials and intermediary/finished goods, and who are no longer convinced that the Almighty Dollar is a necessary part of their future. The control and stabilization of the American economy is not simply a matter of protecting our livelihood, but of national security. Tragically underreported is the unfortunate reality that consumer revolving credit has consistently increased since 2000, reaching a level of almost $1 trillion. This has been given cursory attention, but presents a potential financial time bomb once the student loan moratorium ends. Once that happens, millions of Americans are going to be financially obliterated as they transition from “living on credit cards” to “living on credit cards with even less money to pay them down.” There won’t be any stop to the debt spiral until rates start getting cut, but if Powell cuts rates too soon the resurgent inflationary spike that will ensue will make a return to normal virtually impossible without dramatic action.

We at Garrison Fathom remain pessimistic and are staying patient with our holdings and investments. Our team will continue to monitor and report.

1 Comment

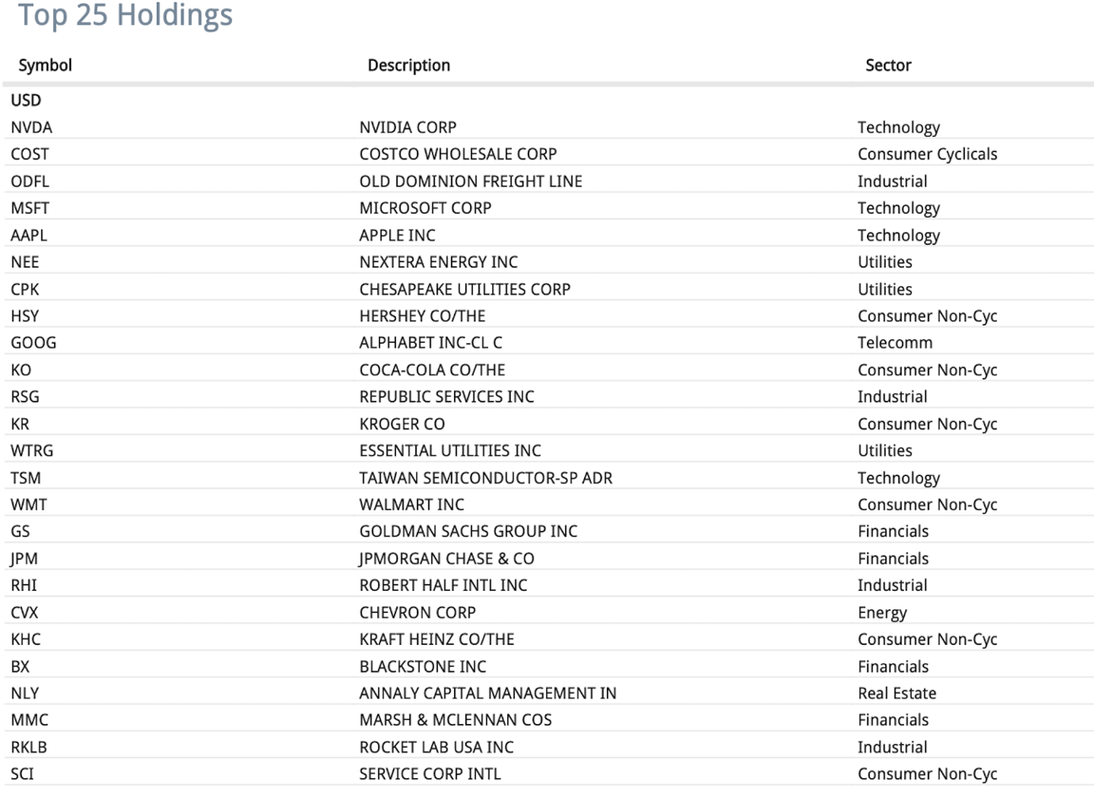

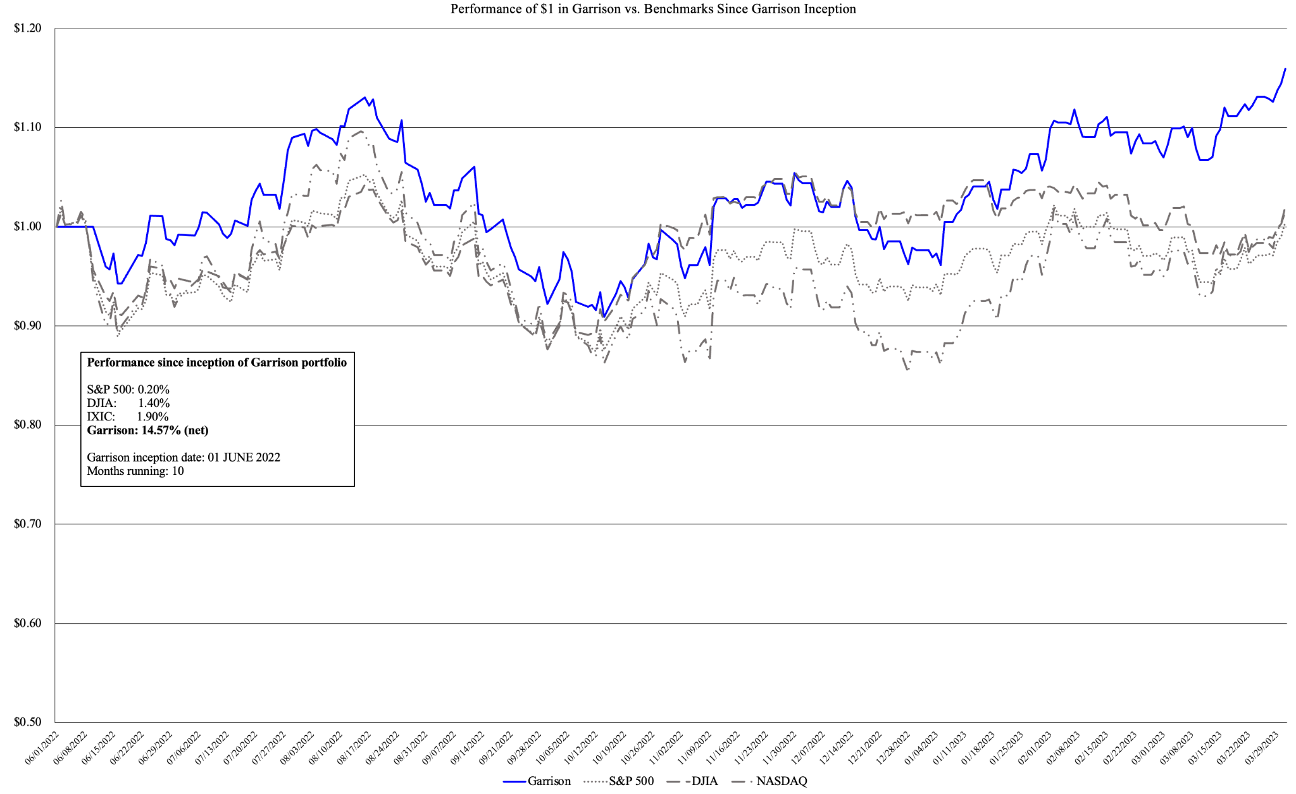

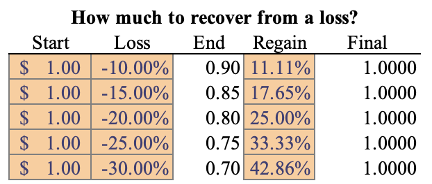

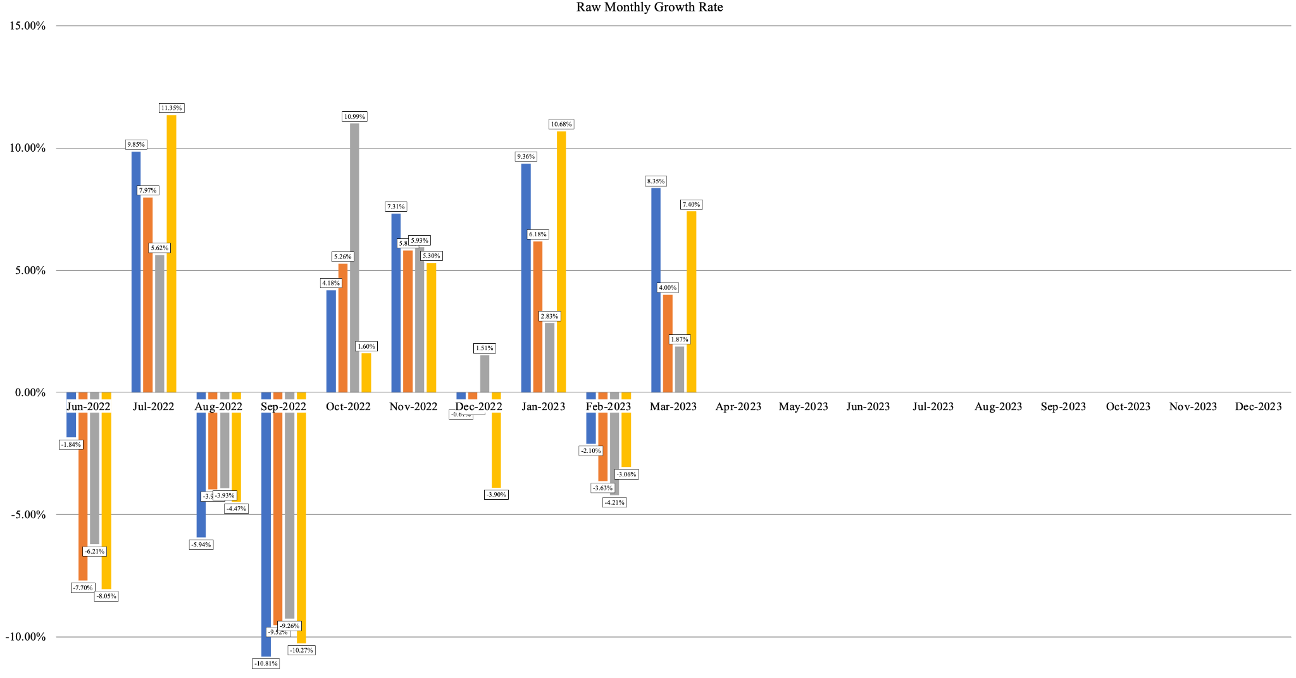

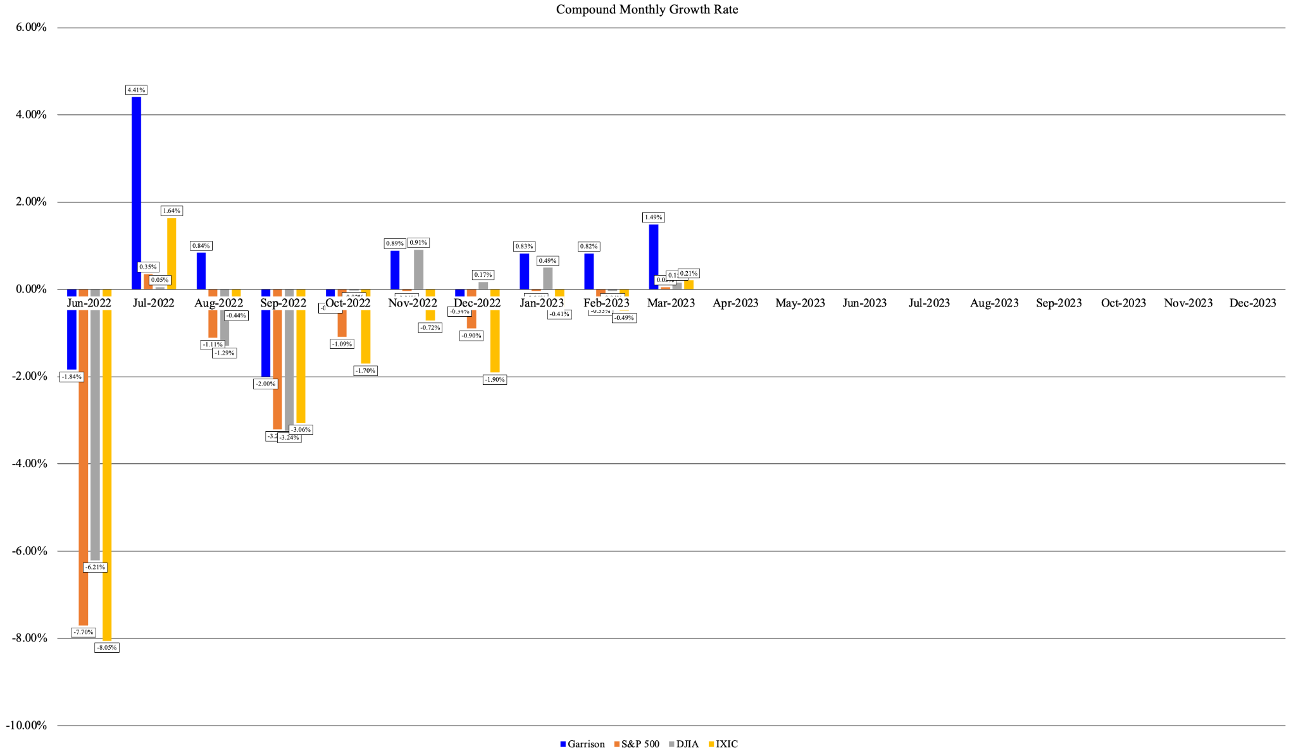

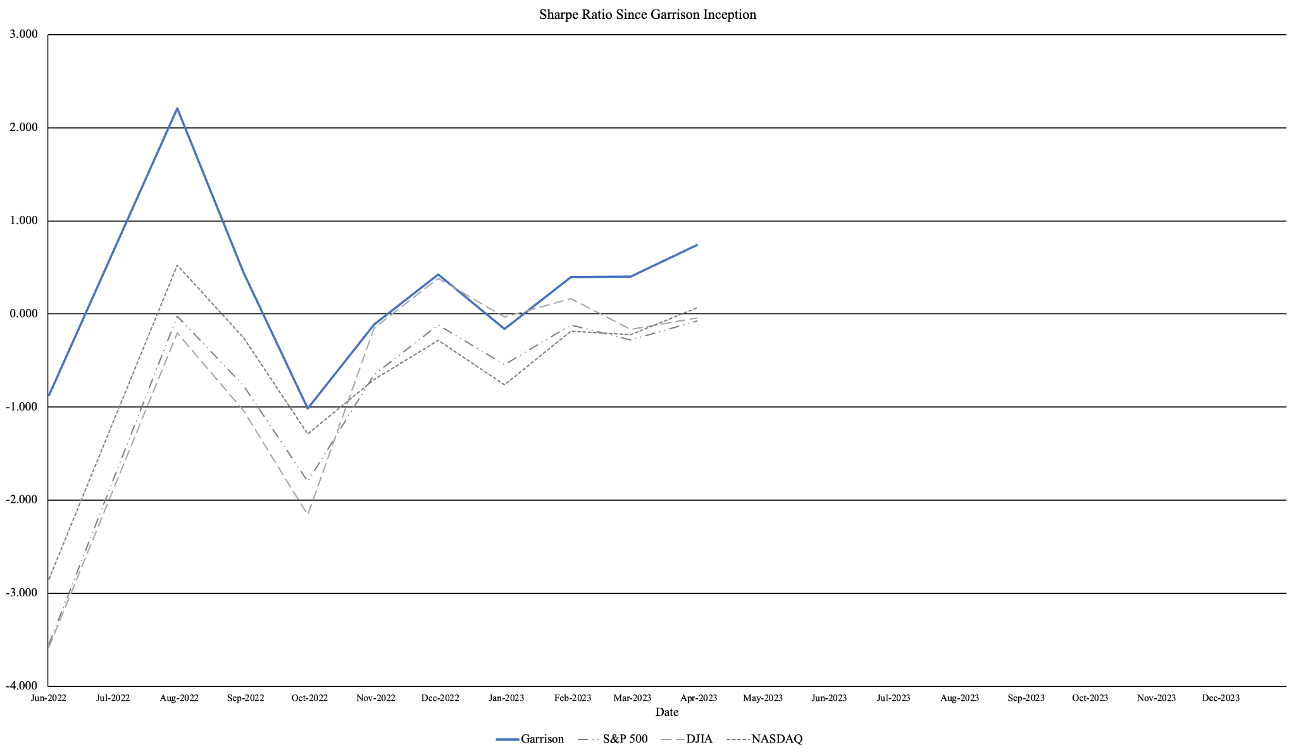

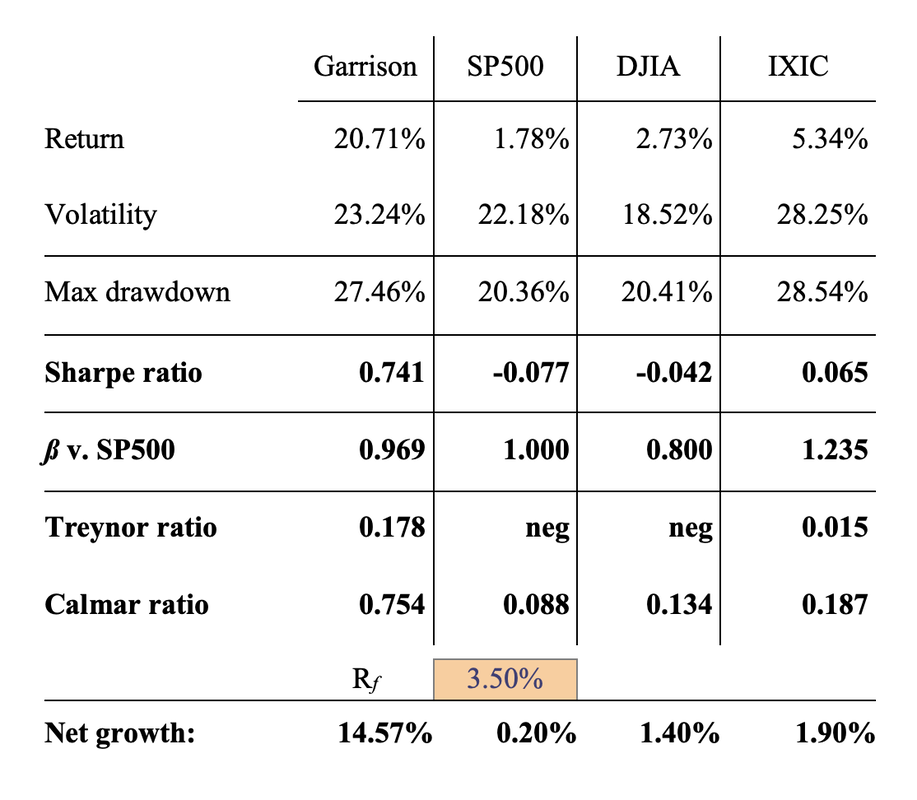

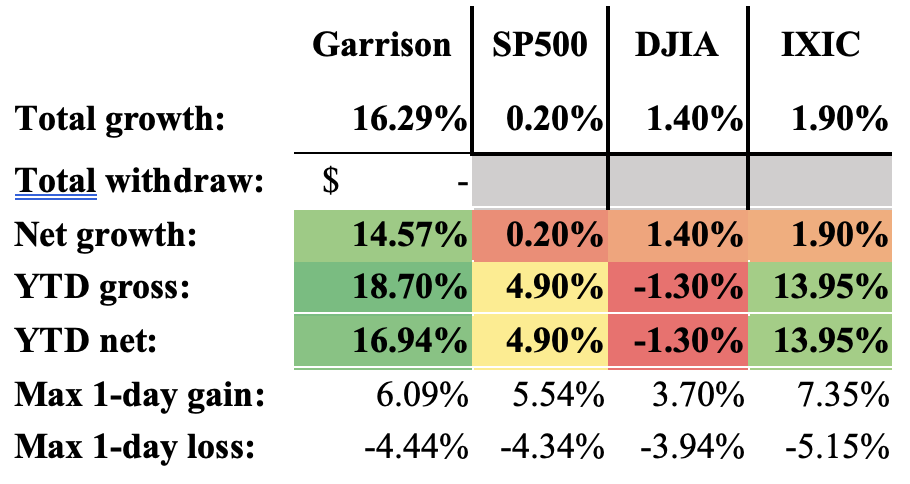

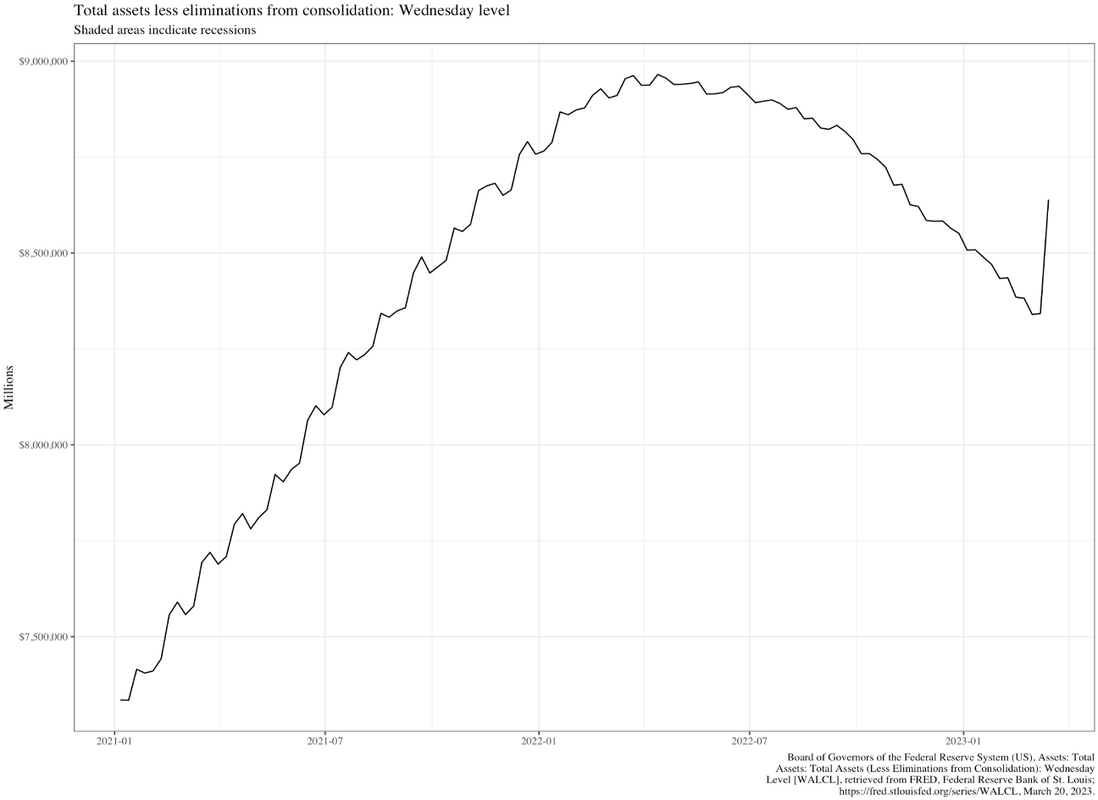

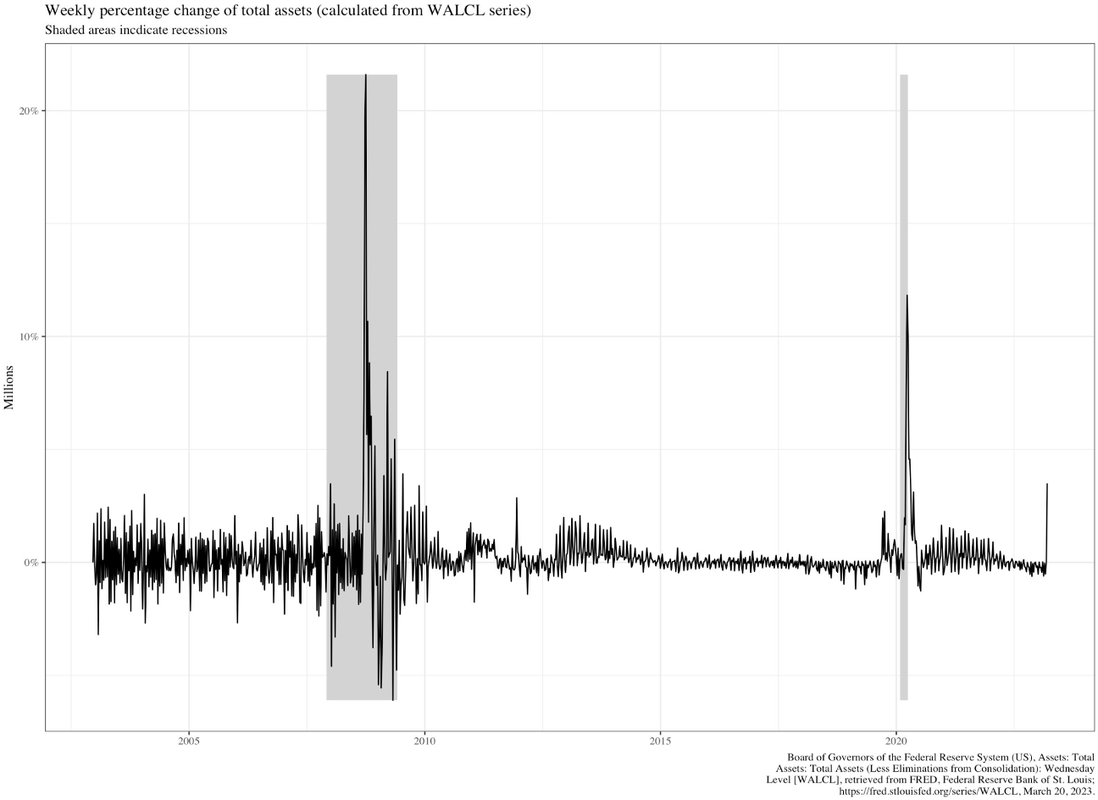

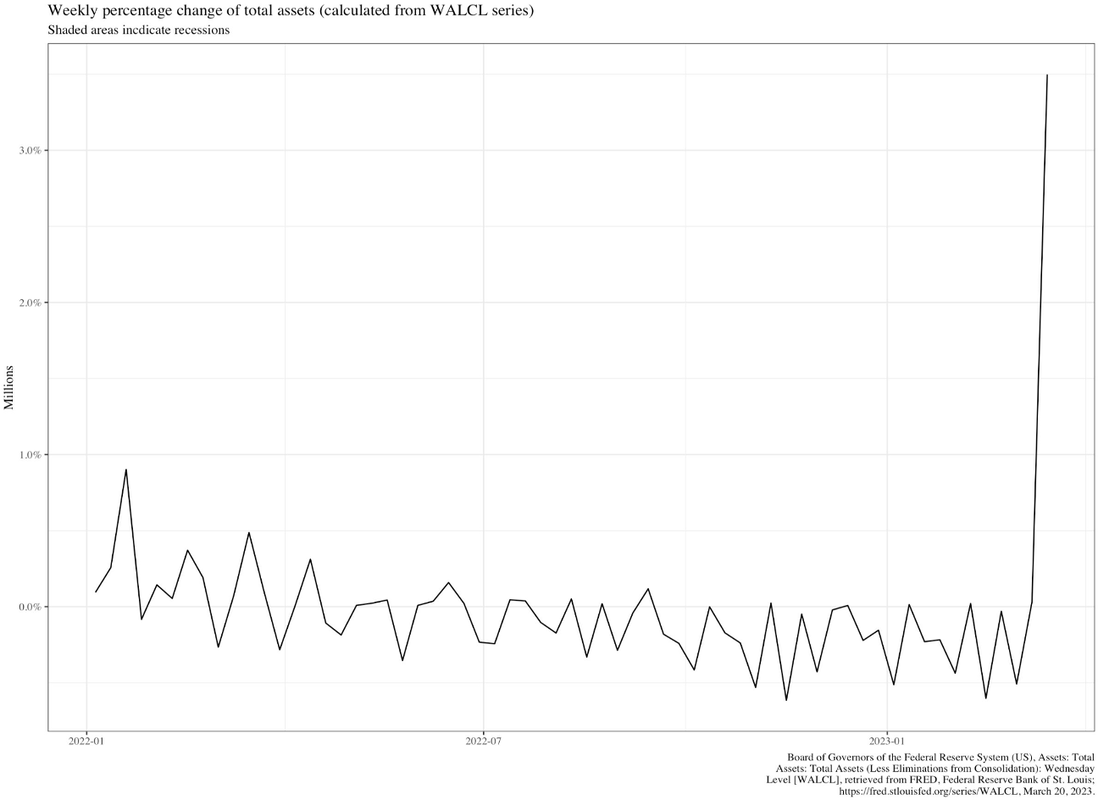

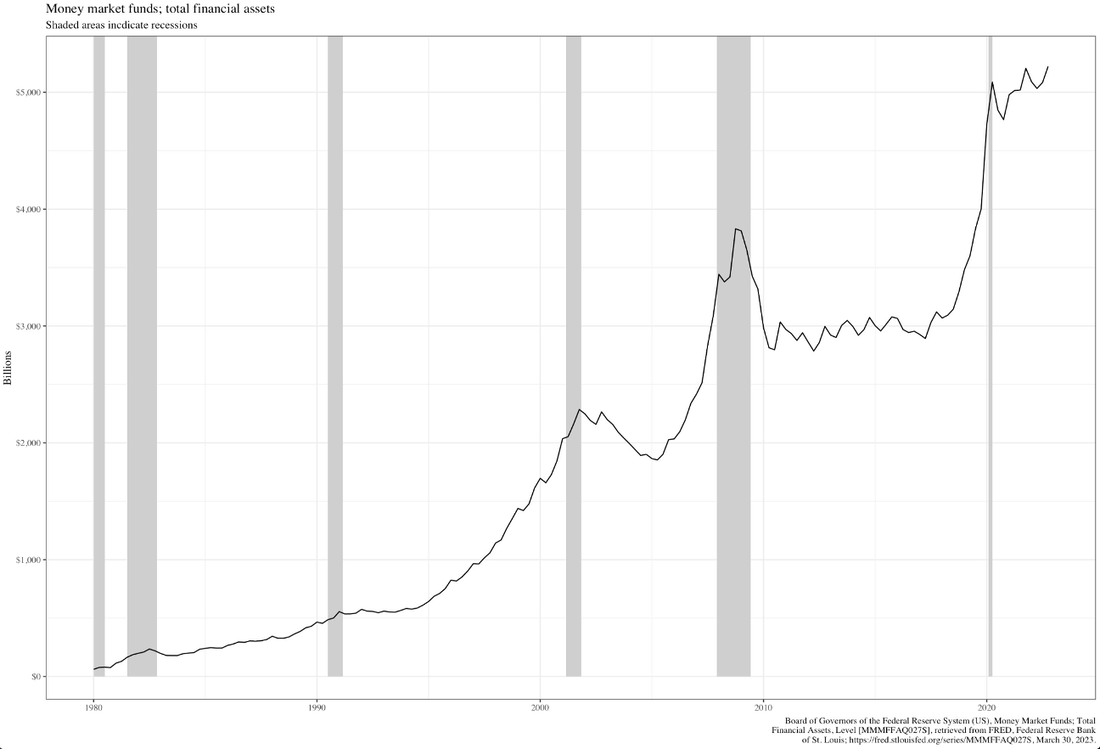

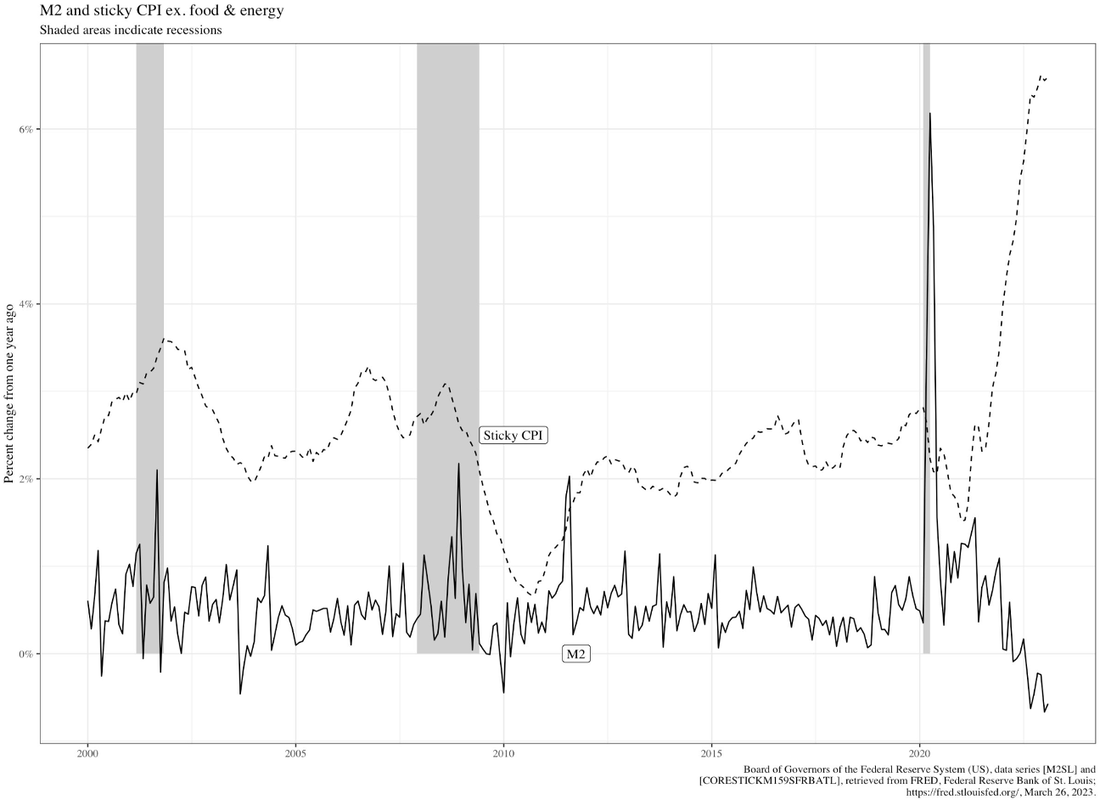

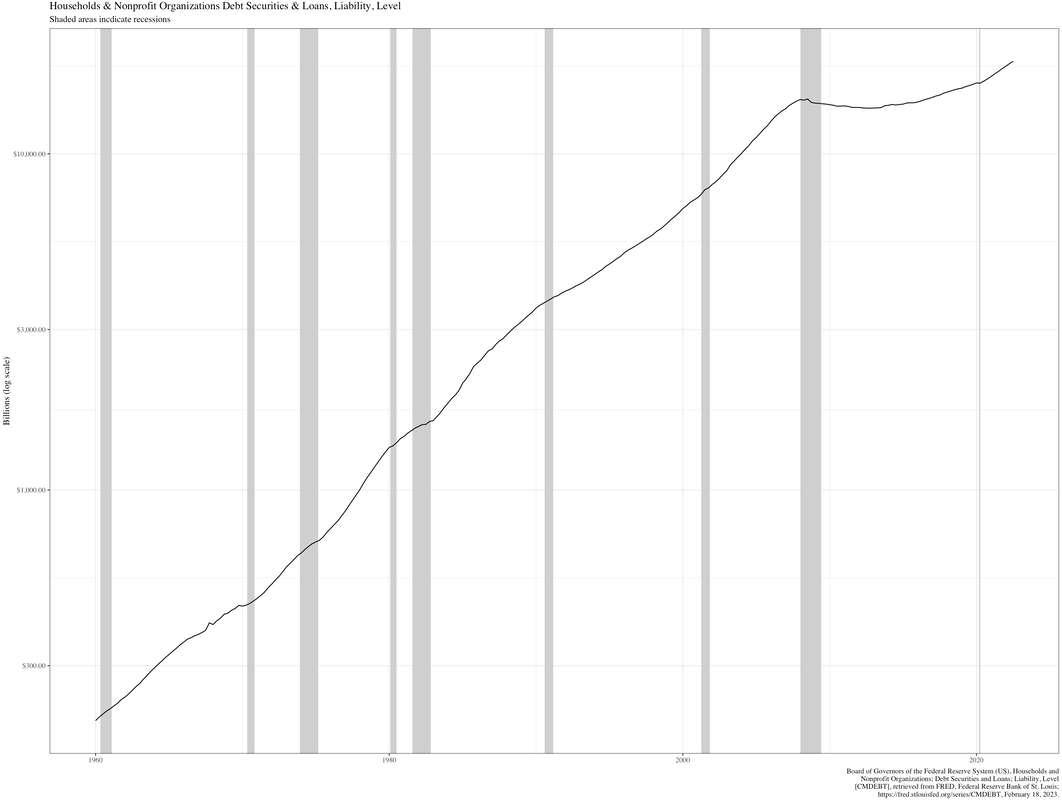

Garrison portfolio up 18.70% YTD, 16.94% YTD net, and 14.57% net since inception The first quarter of 2023 was far from placid: there were multiple bank failures, the BRICS countries dared to take the first step toward de-dollarization, the war of Russian aggression rages on, and the Fed will likely need to continue rate hikes to battle inflation (or run the risk of the economy turning toward stagflation). To make matters worse, global corporate defaults are happening at the fastest pace since 2008, and there are signs that economies in the eurozone are signaling a recession despite the masses maintaining that one or more markets (depending on your particular delusion of choice) will be fine. There is no such thing as “fine” anymore: the world economies are far too interconnected to truly insulate oneself at home from turbulence abroad. But there is still light at the end of the tunnel: proper investment strategy, combined with a long-term vision, remains the most dependable strategy regardless of external factors. The summary of quarterly and YTD is given below. Portfolio allocationThe Garrison portfolio positions are allocated as follows: We have not made any significant changes to our positions during this quarter. Performance since inceptionOn a sufficiently long timeline, the result of superior strategies will begin to emerge. As previously mentioned, the point of the Garrison strategy is to balance volatility with reward by minimizing the former whenever possible. Our portfolio remains firmly invested in staples with strong economic moats and highly-defensible market positions, and our Sharpe-Kelly optimization is beginning to demonstrate performance that is notably superior to the indices. The losses incurred in late 2022 were unfortunate, but as can be seen were losses that were experienced by the broader market. Certain economic forces are unavoidable regardless of positioning; that is the downside of a strategy that relies solely on long-term appreciation rather than short-term cover. The Garrison portfolio shows the benefits of maintaining consistent performance over multiple periods, rather than trying to achieve large gains to cover large losses. In fact, any loss will always require a higher gain just to get back to where one started, as shown below: It becomes readily apparent that the situation becomes supremely dire as the magnitude of the loss increases: a 30% loss within one period (say, one year) would require a gain of almost 43% within the same period to offset. For instance, if a portfolio lost 30% within a year, it would need to gain 43% within that same year – something that the S&P 500 has done only twice since 1930 – to get back to its original value. It is therefore more prudent to minimize losses (or, rather, to maximize potential gain for each unit of volatility) than to optimize gains. Viewed on a monthly scale, the Garrison portfolio has not shown repeated outsized performance relative to the conventional indices: However, when viewed on a compounding scale, the advantage of the Sharpe-maximization approach becomes readily apparent: Similarly, the Sharpe ratio of the Garrison portfolio has grown steadily since the late-2022 downturn: Estimated annual performance since inceptionAfter three quarters, there is sufficient data to begin estimating the expected annual performance of the Garrison portfolio; this, along with the current metrics of interest (Sharpe, Treynor, and Calmar ratios, as well as beta versus the S&P 500) are as follows: Year-to-date performanceThe Garrison portfolio dominated the indices for Q1 of 2023, as shown below: The correlation of securities within the Garrison portfolio is structured to asymmetrically influence the performance of the portfolio: note that the maximum single-day gain of Garrison nearly exceeds that of the famously volatile NASDAQ Composite, with downside comparable to the more conservative S&P and Dow. This is, of course, by design, and Garrison is expected to continue exhibiting similar behavior in the future. Closing thoughts and future outlookHistorically, April has been a good month for stock performance: companies have released their Q4 earnings from the previous year from January through March, and a “spring cleaning” of sorts occurs as weaker companies are identified (or accused) and investors shift capital to stronger prospects for the year. This is not necessarily our approach. While we are always evaluating our positions to most efficiently deploy capital, none of our positions have been entered with a near-term horizon. We are more than willing to absorb short-term drawdowns for long-term performance. That said, there are times when macro forces create obviously (dis)advantageous opportunities for entry without necessarily trying to “time” the market. For instance, we expect rate hikes to continue this year due to the persistence of inflation, although the slower inflation is brought down the higher the risk of a sharp downturn. We’ve mentioned before that the Fed’s response to inflation has been tepid at best, but unfortunately inflation has continued to grow for so long – and to begin adversely influencing economies around the world – that now is probably not the best time to rip the Band-Aid off. That time was in mid-2021; now, we must be satisfied with incremental hikes and hope for the best. There are other recessionary signals to consider. First and foremost, the Fed’s balance sheet remains high, no doubt due to the grand experiment of quantitative easing from which we’re still trying to recover. As the following images demonstrate, the Fed’s balance sheet is normally sideways or changing gradually; sharp increases, such as those during the Great Recession and 2020, tend to have knock-on effects that are usually less desirable than the irrational market exuberance they cause. There have also been rather concerning upticks in the total assets of money market funds. While these are typically a safe way to protect assets during a downturn, they are not ideal for long-term growth; however, they do provide some often much-needed liquidity during a recession. Historically, sharp increases in money market fund inflows have presaged a recession; if one were to believe in the hypothesis of a (semi-)efficient market and that asymmetric information is eventually priced in, the fact that the post-2020 downturn in money market inflows was so short-lived should be concerning. This leads back to the question of inflation and debt, as almost all macro observations must. Currently, the total amount of revolving consumer credit is the highest in sixty years – over $1.2 trillion. Debt is not in and of itself undesirable – the key is what an investor (or consumer) can obtain for every dollar of debt incurred – but when debt is combined with broader adverse conditions, the perfect conditions for a catastrophe are formed. The real terror is seen when examining the year-on-year change in M2 and sticky CPI: The post-2021 divergence between the two is only part of the danger: the year-on-year change in M2 has not once been this negative since 1960. The sharp decrease in M2, combined with the sharp increase in revolving consumer debt, highlights what several news outlets have mentioned: Americans are increasingly relying on credit card debt to fund normal activity, which will create an incredibly undesirable feedback loop as the Fed continues to raise rates and credit card companies follow suit. The divergence of the above chart suggests that the sharp decrease in M2 is due to a decrease in savings, which is logical given the still-hot inflationary environment.

Americans are teed up for a perfect storm of economic misery: high debt load, potentially still-high interest rates, and a contracting economy. We foresee that if a recession is to occur – the data suggest that this is highly likely – it will likely begin late Q3 or mid-Q4 of this year. With that in mind, we are evaluating several industrial companies that will enhance the value of our portfolio, but we will not be taking positions within them until it becomes clear that we are either deep into a recession or obviously clear of it. We are also evaluating several agricultural companies (specifically grains, oilseeds, food processing, agricultural storage, fertilizer production, and transportation) that show good promise for sustained performance even during a downturn: no matter how bad the economy, people still need to eat. Similarly, we are examining potential opportunities within utilities and logistics. The coming quarter is a momentous occasion, as it will mark the conclusion of the first entire year of performance for the Garrison portfolio. We look forward to a potentially volatile quarter that will continue to demonstrate the merits of our philosophy of sound investing in fairly-priced companies with excellent long-term prospects. The concept of a bank, as a formal financial institution, has existed since at least 1472. The first public securities market was opened in 1611. You’d think we as a society would’ve gotten things right by now, but the recent collapse of Silicon Valley Bank proves otherwise. Bank failures in and of themselves are nothing new – over 9,000 failed just during the Great Depression (and without the benefit of FDIC insurance… ouch), and from 2009-2023 there were 512 bank failures in the US alone. In fact, bank failures (yes, in the US) are so common that years like 2005, 2006, 2018, 2021, and 2022 – when there were zero bank failures – are the exception. Even since the start of the coronavirus pandemic and prior to the collapse of SVB, only three banks in the US failed, and all three had experienced previous financial problems. SVB’s collapse was actually the second-largest in recent US history, right behind the fall of Washington Mutual during the 2008 crisis. Banking basicsSVB experienced a good old-fashioned bank run, plain and simple. Until the panic started and depositors tried to pull their money out – which escalated to the point that police were called to handle the crowd – the bank was nowhere close to insolvency. But when some of the Valley’s “whales” (including one investor whose portfolio companies purportedly pulled a total of $1.5 billion from the bank) began heading for the exits, this created the same self-fulfilling prophecy that financial institutions have feared for centuries. So why the panic? Part of it is human nature, and another part is mathematics. Banks aren’t typically in the business of holding enormous stacks of cash for no reason: they must make money to pay employees, etc., just like any other business. They do this by giving out loans and collecting interest. Typically, a bank will only keep enough cash on hand to meet the higher of two criteria:

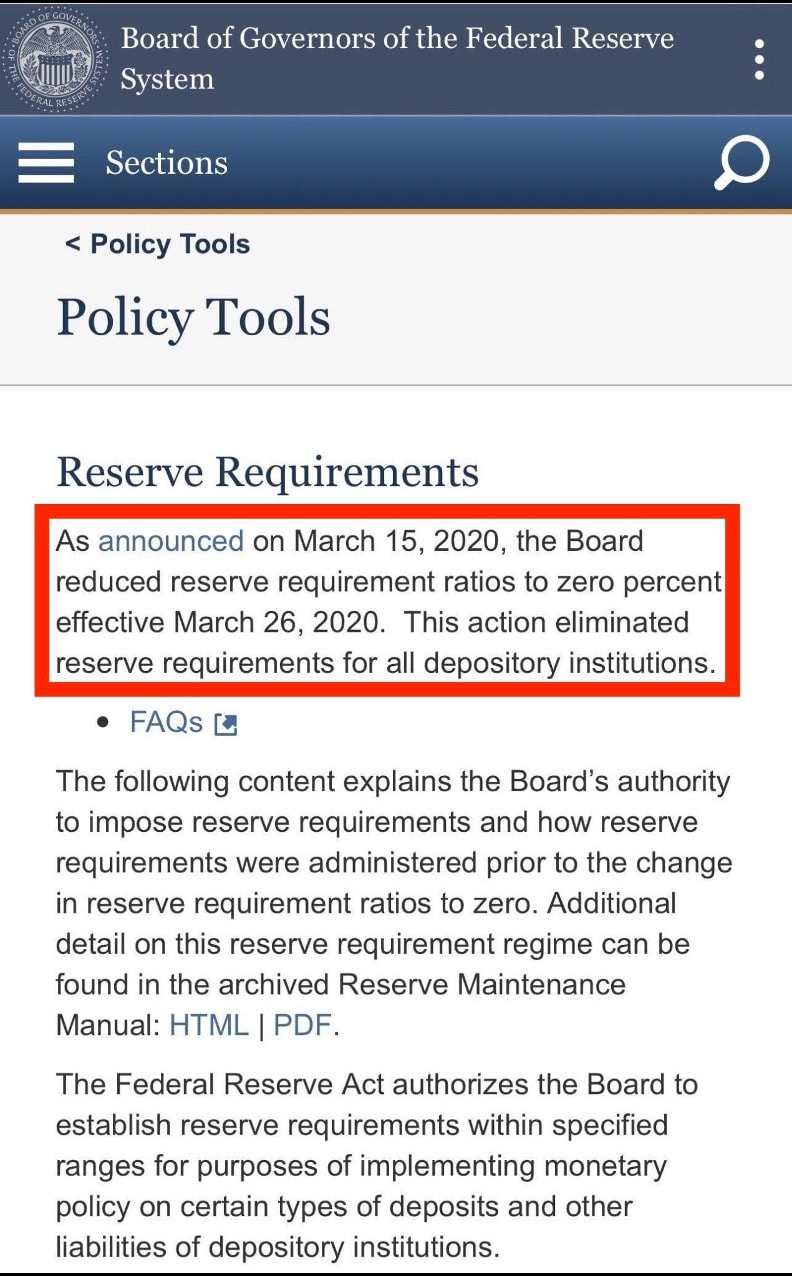

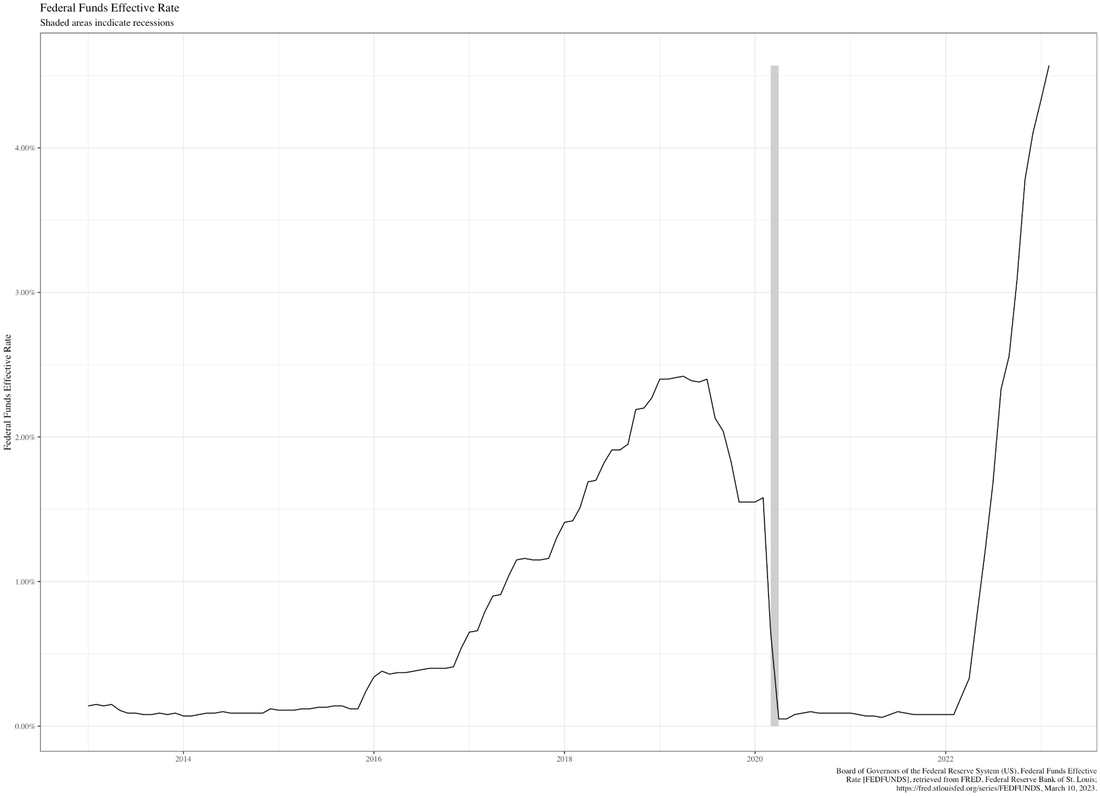

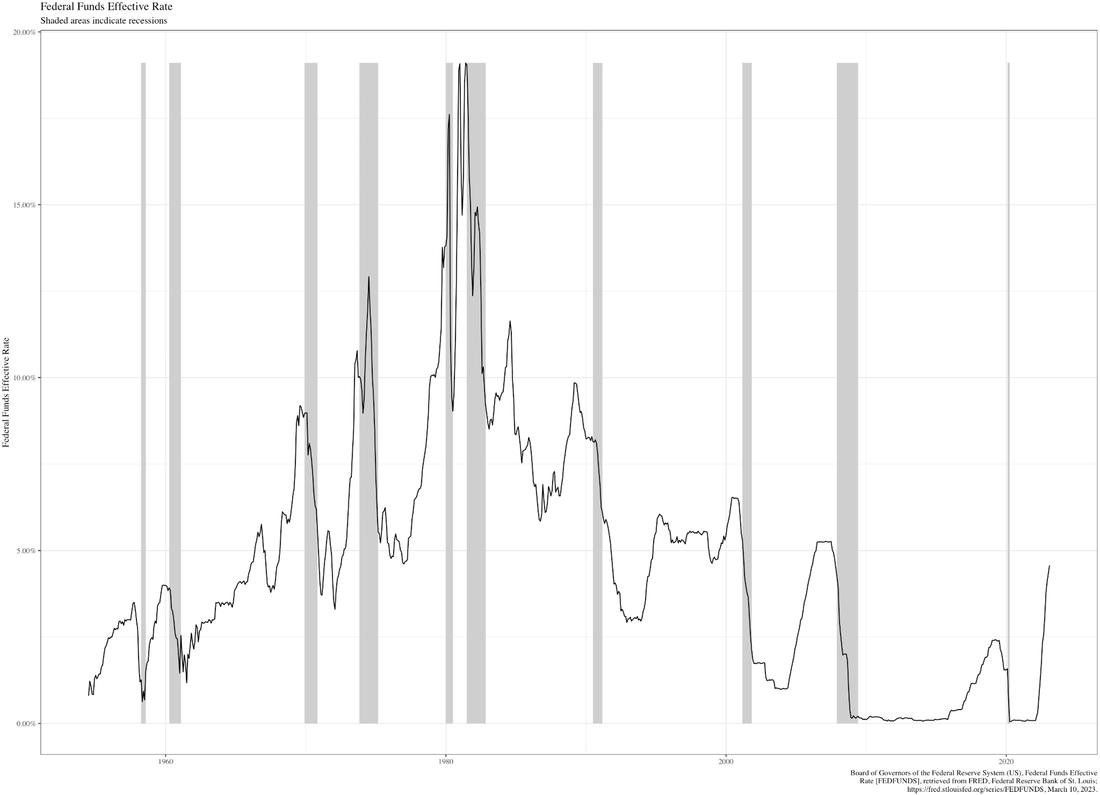

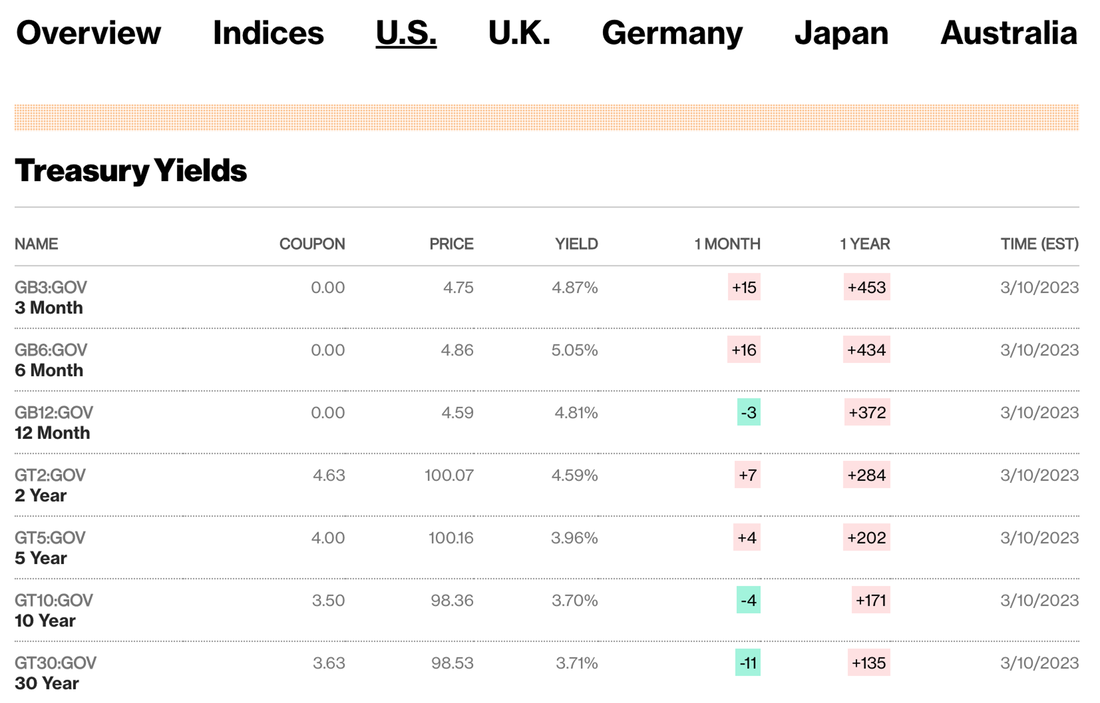

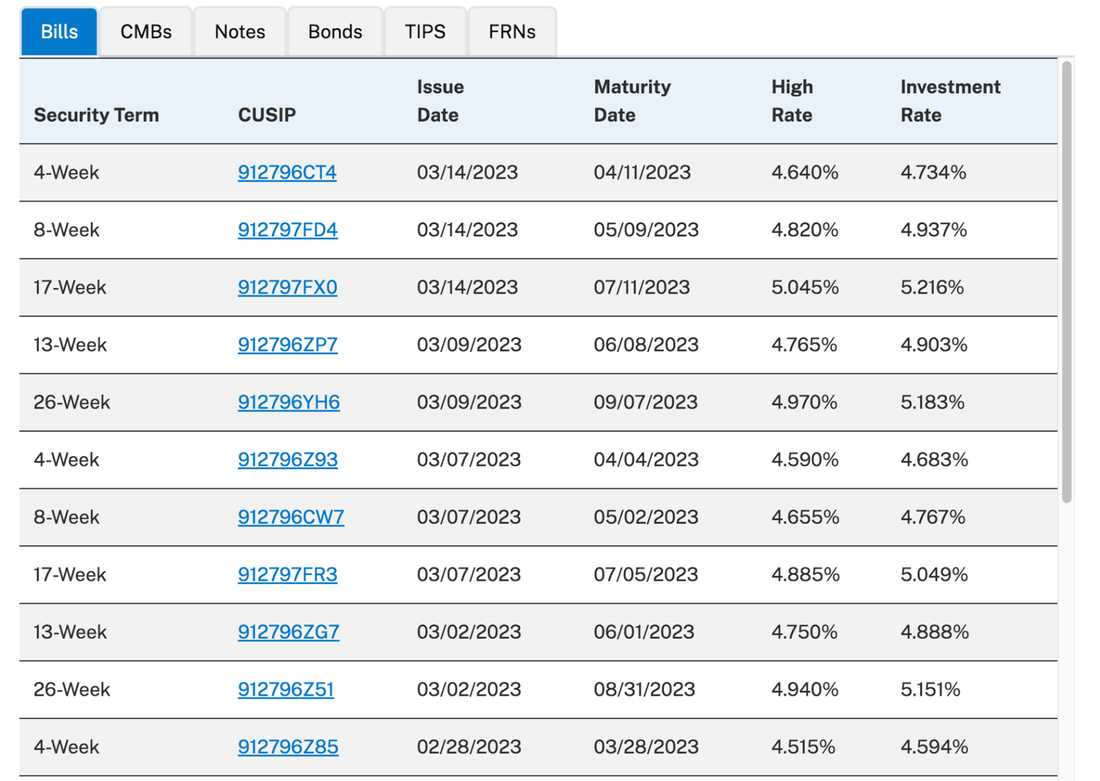

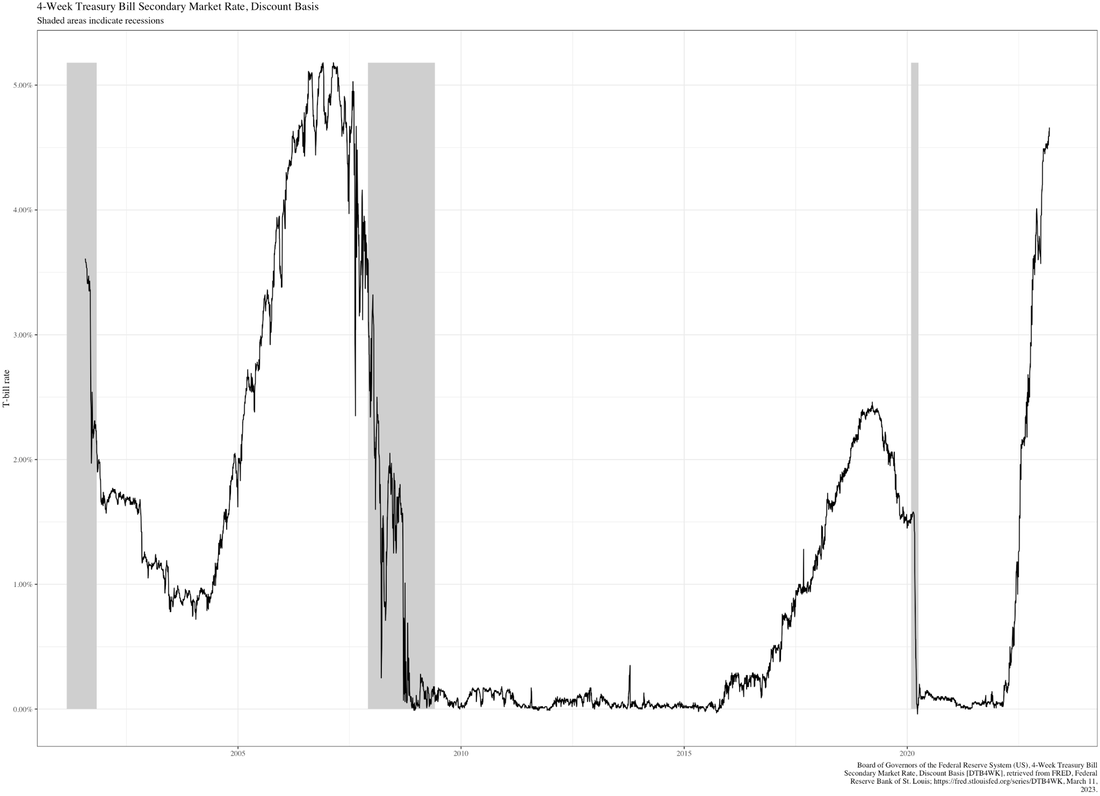

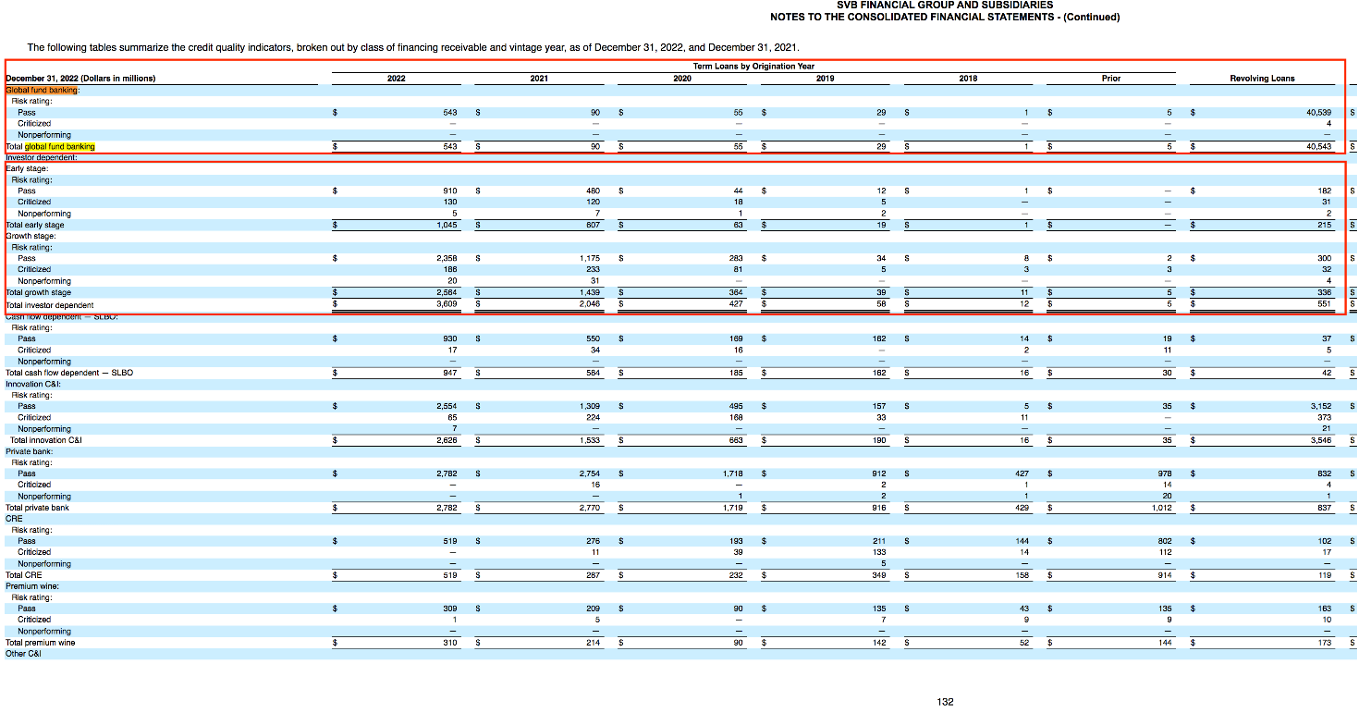

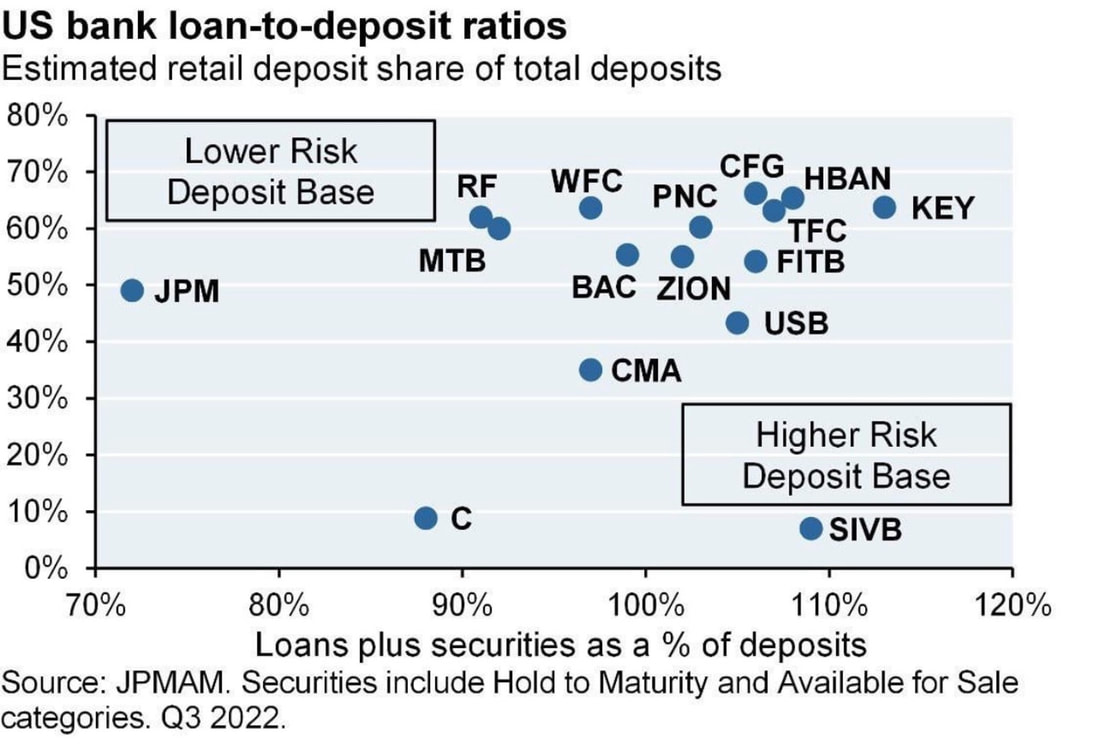

Of course, banks would prefer to only keep the amount of money in reserve that’s necessary to meet operational requirements: while the Federal Reserve began paying interest on deposits in 2008 (known as the interest on reserve balances, or IORB, which reached a whopping 0.10% in 2022… about as bad as the rates offered to savings account customers), banks can be much more profitable by making loans and collecting interest. These capital requirements have changed over time, and despite arguments from the banking industry that higher capital requirements harms economic growth (by forcing banks to reduce lending or increase the cost of capital), the reality is that both capital requirements and lending have increased between 2013 (when higher reserve ratio requirements began taking effect) and 2020. Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve decided to set the reserve requirement to zero: This period of zero reserves was short-lived, and by February of 2023 the reserve requirement had increased to a much more conservative… 1.27%. Meaning that almost 99% of a bank’s deposits were “out in the wild,” as it were, providing capital to loan customers, rather than sitting in the vault. Assumptions that this is not much to fall back on in tough times are both chilling and correct. So if capital requirements aren’t directly impacting lending activity, what does? Quite simply, it’s interest: loans are nothing more than the result of a bank calculating opportunity cost – if they can make more money lending to you (yes, factoring in credit risk, probability of default, loss given default, time value of money, etc.; they’re businesses, not charities), as opposed to holding reserves and collecting IORB, then they lend to you. But this mindset in many ways ties the hands of banks to the broader economic climate. Why did capital requirements and lending both increase between 2013 and 2020? Well, for starters the interest rate environment was significantly different than today: In fact, until the current economic turmoil, the Federal rate had been nearly zero for years, and even today, with all the crowing about the “brutally high” interest rate environment, it’s readily apparent that neither Wall Street nor Capitol Hill are in any danger of looking at history with even an ounce of critical thought: This interest rate environment provides a critical insight into why SVB collapsed. The bottom line is that anyone can make money when times are good – that is, in fact, why good times inevitably lead to hard ones – but it’s only when the markets turn that sanity is put on hold and proper financial strategy shines. Anatomy of a collapse: a semi-deep diveThe bank run on SVB illustrates one of the key flaws inherent in much of the financial system (which we’ve covered before): it depends almost entirely on the origination, packaging, and reselling of debt, which in turn locks you to the whims of interest rates. But we're seeing what happens when the Fed continues to hike interest rates – to the point that a 2-year Treasury is exceeding 5%, which in 'normal' times is the cost of capital of most firms – and banks like SVB are forced to sell their bond portfolios at a loss just to have liquidity. SVB’s collapse is directly traceable to an unforced, unnecessary, and self-inflicted error: that of management choosing to sell $21 billion worth of bonds at a $1.8 billion loss. Why? Because those bonds were yielding less than 2% at a time when buying Treasurys could yield more than double that. The bank’s bond portfolio was underperforming relative to peers (on paper, anyway), and SVB were faced with the threat of Moody’s downgrading its rating (of course, the true value of a high rating from a credit agency is itself suspect). With the help of Goldman Sachs, who may have been searching for some way to draw attention from an executive allegedly participating in one of the biggest heists in history, SVB chose to raise new equity capital and sell a convertible bond to the public. The core issue is one other banks would be wise to be aware of: SVB had invested customer deposits in low-yield bonds that were on the books on a hold-to-maturity basis. This means that they didn’t have to mark those bonds to market until they were sold. So long as the bank didn’t sell those bonds, there was no problem: the balance sheet, although distorted, would have remained stable. It’s only when the bank sells these bonds to meet withdrawal requests that things become painful. This entire ordeal will undoubtedly spawn a detailed and protracted postmortem that will lead to much sabre-rattling in Washington – all sound and fury, signifying nothing. Why would SVB do something that appears so suicidal in hindsight? Well, to ease investor sentiment, of course. Whether the fire sale of the bonds or the fundraising was the first to trigger panic is unclear (and may never be entirely without argument), as is whether either action was made under duress. What is known is that the actions spooked the bank’s clientele, many of whom are extremely educated and financially literate, and who in response began pulling their deposits en masse. Remember the reserve ratio? In the United States, it’s never been 100% (nor would there be any logic in making it that high), which means that no bank is required to hold more than a small amount of customer deposits at any given point in time. But while the SVB collapse may be an outlier (even in Silicon Valley, where failure is itself seen as a merit), the fallout may not be known for a while yet: SVB wasn’t the proverbial Nowhereville Savings & Loans – it didn’t hold a lot of retail deposits like the Chase branch down the street might – but banking crises are like cancer: the death of one bank can affect the likelihood of others failing, depending on which bank is exposed to what types of risks caused by the failing institution. Why not [...]?The first question on many people’s minds is likely: where’s the FDIC in all of this? Not only was SVB allowed to fail (you could argue that it was forced to fail, since DFPI decided to close it down), but isn’t that also guaranteeing that everyone’s accounts were also allowed to fail? Not necessarily. SVB was FDIC-insured, which means those deposits are guaranteed… unless they exceed the limits imposed by the FDIC, because the FDIC can’t insure all deposits for all customers at all banks. FDIC doesn’t just hand out insurance on a whim: not only must insured banks meet the standards set forth by FDIC and pass periodic examinations by the FDIC’s Financial Institution Specialists (“fizzes”), but they must also pay a premium on their deposits. Yes, banks must pay for FDIC insurance, just like one might have to pay for car insurance, because the FDIC actually receives zero money from Congress – in one of the rare examples of governmental efficiency, the FDIC is entirely self-sufficient, with its budget supplied by the premia paid by member banks. Increasing deposit insurance by default means increasing the premia paid by banks. Recall that banks make their money on spread: they charge a higher rate on loans (i.e. money they receive in the form of profit) than they pay out (to holders of savings accounts, bank products like CDs, and to the FDIC). The real time bomb might be that the FDIC insures trillions of dollars on an operating budget about 400x smaller than that, and a net income that is still dwarfed by the amount insured. If you increase the operating cost of a bank, you’re forcing it to charge a higher interest rate on its loans. Do you think the current interest rate environment is too damn high? Imagine that being permanent. “But why don’t banks just decide to make less money? It would be better for the economy!” Why don’t you decide to voluntarily take a pay cut? It would be better for the company, wouldn’t it? The typical net profit for a bank – at least one that isn’t a financial superpower that can enjoy massive economies of scale – is about 10-15%. That’s certainly better than some industries (education: 2.92%; air transport: -1.71%). But a bank is just like any other business in that it must set aside funds for rainy days… such as those we’re facing right now. What was management thinking?Honestly, we might never know, and it’s unclear if even SVB’s managers understood the consequences of their decisions. To be honest, there’s already a lot of pressure to transfer cash to short-term Treasury bills and bonds, especially considering that the yield on a 3-month T-bill is nearly 5%: This isn’t shocking: when the Fed raises rates, Treasury yields rise. Recall that a Treasury instrument is “as good as cash” (it’s considered a cash equivalent). Even the rates on the shorter-duration T-bills is nearly the same as the historical market risk premium: For comparison, the only time this millennium that the four-week bill has been higher than the current rate was in 2007: This shouldn’t surprise those who read this post: the Fed took a lackadaisical approach to tackling the “transitory” inflation problem caused by massive coronavirus relief spending; and contrary to Chair Powell getting called out for rate hikes, which are one of the Fed’s only tools for fighting inflation, the massive injection of capital into the economy was a measure that enjoyed bipartisan support. Powell is neither saint nor sinner in this regard: central banks are always behind the curve when it comes to policy lag by simple dint of humanity’s complete lack of clairvoyance, and the effects of a systemic shock are impossible to immediately recognize, and are also impossible to immediately fix. Notice that no real-world economic data are as smooth as those found in textbooks: in what is perhaps the understatement of the century, we must reiterate that economies are far too large and complex to constantly “fiddle the knobs” to affect uncertain effects on an unknowable future. Hindsight is both 20/20 and occasionally overrated: in a certain perverse way, Powell’s initial lack of action may have been necessary – markets require stability to function, and repeated fiddling can cause more harm than good. That said, such an enormous spike in money supply probably should’ve raised a few more eyebrows… Should this have been expected?SVB’s managers (who may or may not all now be out of a job) invested short-term deposits in long-term assets. That’s the long and short of it. But anyone who’s been awake the past couple of years should have suspected that the massive pandemic spending would fuel inflation and thus necessitate rate hikes. And contrary to what many are saying, SVB was not a bank run by gambling-addicted degenerates: examining its most recent 10K shows that the bank actually exceeded Basel III requirements for CET 1. US banks under Basel III have been de-risking for years, and SVB was no different. According to SVB’s SEC filings, yes, SVB did in fact participate in This is hardly the hallmark of a cabal of degenerate gamblers out to ruin innocent investors and depositors for personal gain. Global Fund banking is actually very safe: it’s mostly funding venture capitalists to make transactions while they await a capital call. In other words, if a venture capitalist wants to fund a company but they have to wait (one week, one month, two months, whatever) for drawing down from their LPs (the people/institutions that actually provide the venture capitalist with money), then the VC will ask for a line of credit for this purpose. Venture and private equity funding is contracted, and historically the default rate of venture funds themselves is very low – contrary to popular belief and Silicon Valley’s penchant for high-risk endeavors, VCs are not stupid, and they tend to prefer to not lose money. These VCs were over-collateralized through the value of their homes, typically on the order of 150% of the loan value. Does this seem risky? Maybe to some, but this is Silicon Valley: home prices are relatively stable, even during recessions. In fact, for the past 20+ years the price of homes within Silicon Valley have mostly stayed within a band on +2%/–1%, with only occasional excursions beyond that: The investor-dependent portion of SVB can also have been considered safe, as these loans were basically bridge financing for when a round had already closed (viz. capital already committed) and there was a lag between when papers were signed and when money was transferred. In other words, SVB was a bank holding a large portion of its book in government paper and the rest in pretty safe lending. The “speculative” portion of its book was miniscule. This is in wild contrast with Silvergate, whose implosion was driven by a pivot into cryptocurrencies and was, arguably, entirely deserved. But a conservative book does not equal conservative management, as we have all witnessed. SVB catered to a very unique clientele that had high withdrawal needs and should have focused on holding more shorter-term securities. Yes, “woulda-coulda-shoulda,” but when this clientele requirement is literally part of your business model, management decisions should be made to accommodate: barbells aren’t just for the gym, and ladders aren’t just what you find at the hardware store. Long-dated bonds are not cash equivalents unless we’re in a declining-rate environment, which careful research (called “Googling”) will reveal has not been the case for years. In a rising-rate environment, long-dated bonds are as liquid as solid rock, turning what is normally an investment opportunity into a very real, very devastating loss. In short, SVB’s balance sheet grew massively over the past five years. Most of this money was used to acquire long-dated bonds to serve a clientele that required very immediate access to capital. Rising rates forced SVB to try and acquire capital, which it failed to do before the information became public. The subsequent run rang the death knell. The Fed only built SVB’s coffin – poor management is what shoved the bank into it, nailed it shut, and then encased it in cement. Frankly, the level of incompetence shown by SVB management is staggering, especially for a bank whose CEO literally served on the Board of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. The fact that SVB execs sold over $4 million just a couple of weeks before the bank collapsed, even if found to be purely coincidental, is not a good look. How wide will this spread?Duration mismatches in book value and mark-to-market value for held-to-maturity investments are expected: the price today (when you book) is not going to be the same as the price tomorrow (when you sell) because what drives the sell value of a bond (interest rate) is going to change. Rates go up, value goes down – that’s Finance 101. Average maturity in SVB’s book was about six years: when bonds are sold, they’re marked to market, and a sharp drop in book value (due to rising rates) can easily wipe out a large portion of a bank’s value. As was the case with SVB. The real question is: who will actually get hit the hardest, and what will be the follow-on effects? SVB was not a stupid bank run by stupid people – if anything, it was very cautious – but no matter how conservative you are, you’re never going to survive a bank run unless you keep 100% of deposits on hand, 100% of the time. In that case, you’re not a bank, but a bank-shaped economic black hole that’s doing nothing but losing money. That would be irresponsible; making loans and following FDIC and Basel standards is not. The real wild card in this scenario is the fact that a large portion of the money held was going to startups, who are themselves extremely funding-dependent. When a major fund pulls out all of its money from SVB, as Founders Fund did, a run is inevitable. As an interesting (if morbid) historical footnote, SVB may have been the first victim of a social media-fueled bank run. The pain is going to start when startups can’t meet payroll and have to lay off workers – something which the larger companies have been doing for months. It is absolutely not a worker’s market in the Bay, and may not be for some while. If most of SVB’s accounts were above the FDIC insurance limit – and it seems that most were – then over the next couple of weeks to months (maybe years?) depositors might get back 90 cents on the dollar, when it’s all said and done. That’s better than getting nothing back, but just as SVB’s bonds were mismatched to requirements, so too are the FDIC’s machinations to resolve these issues: you need money today, but you’ll get paid next year. That’s not great. Also not great is the amount of deposits, as a percentage of SVB’s total deposits, that were even insurable by FDIC: SVB had very few retail deposits (the money of “average Americans”) as a percentage of its total deposits, but the deposits it did hold (by definition, non-retail, aka commercial and high-net worth entities) was therefore correspondingly high – and therefore of higher risk. JP Morgan may actually come out of this unfolding debacle (and subsequent bank collapses are sure to follow) as the only real winner. Some of the Valley’s darlings are probably going to be hit the hardest: Roku, for instance, held about $487 million in SVB, or about 26% of its cash; other companies such as Etsy and Rocketlab have also had their cash exposed due to SVB’s collapse. Fears of contagion are already global, and it’s unlikely that SVB will receive any help – in fact, executives in the Valley have already heard that they will receive no bailout from the federal government unless there’s clear evidence of widespread bank runs. And there is evidence of such a threat: see, it wasn’t just Silicon Valley startups that had their money in SVB: the bank had branches in China, Denmark, Israel, Sweden. In the UK, startups were canvassed to ascertain their exposure to SVB’s collapse, burn rate, and access to cash; in Canada, SVB had over $400 million in secured loans (double from the previous year); Shopify, HLS Therapeutics, and AcuityAds are exposed to SVB’s collapse (AcuityAds alone had more than 90% of its cash in SVB). Smaller banks like First Republic, The federal government, to its credit, is aware of the importance of preventing a cascading collapse of financial institutions. As such, they’ve stated that they’re easing the terms for accessing the discount window for SVB clientele. There’s even talk of federally guaranteed all deposits at all banks, which is rather interesting since over $13 trillion is held in “just” the largest banks but the current balance of the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund is only $128 billion. By comparison, MIT estimates that the entire cost of the 2008 bailout was a “mere” $498 billion. Of course, the Fed could simply print more money, but that will create an entirely new series of problems. The larger, “systemically important” banks can likely absorb the shock if the bank runs cascade, but the smaller locals and regionals won’t. The current administration’s war cries of a populist revolution will fall flat once the larger behemoths step in to provide banking services to millions of Americans who might quite literally be left without any other choice. Regardless of the fact that the Deposit Insurance Fund cannot come anywhere close to covering all assets held by banks, the contemporary philosophy seems to perpetually orbit one answer: SPEND. We’ve seen what that has done to inflation. The likely cash crunch that many companies will experience will probably lead to mass layoffs, which obviously spikes unemployment and reduces spending, putting recessionary pressures on the economy. Unfortunately, since the smaller banks will die first, and since those banks are located throughout the country, this scenario may see layoffs occurring across the country more or less simultaneously, rather than in waves (in either the numerical or geographic sense). This will force the Fed to slash interest rates to jump-start the economy out of the recessionary spiral that these mass layoffs will create. But wouldn’t inflation still be high? Of course it would be, and what the Fed needs to do to fight inflation (raise rates) is the exact opposite of what it needs to do to ease recessionary trends. We were called “alarmist” when we said the US was headed toward stagflation, a term that most economists find so filthy and utterly detestable that for decades it was decried as impossible. Welcome to economic hell. Why is this political?The short answer is because everything has to be made political one way or the other. Politics exacerbates economic woes, but we as a country can’t seem to kick the habit. There’s plenty of argument to be made that the FDIC and OCC are somehow partially to blame for the SVB collapse, but in our experience the government only sets the standards that banks must follow – they’re not actively involved in the strategic or operational management of them. That said, we’re facing the very real possibility that tens of thousands of the country’s youngest and brightest workers, many of whom are responsible for the trillions of GDP that are directly traceable to high-knowledge professions (e.g. tech, biopharma, engineering, science) are going to find themselves out of work. That alone would make it a political issue, and the risk of industry consolidation and increased risk to the larger banks makes it moreso. The government’s response to the SVB collapse will likely increase the concentration of power within the banking industry, ironically reinforcing an oligopoly that was itself decried as being dangerous to the average American. The other option would be to turn the systemically-important banks into government-sponsored entities, like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (or the eleven Federal Home Loan Banks, the National Veteran Business Development Corporation, or the SLM Corporation [“Sallie May”]). There’s some precedent for this – FCBanks and Farmer Mac are both GSEs – but one does not have to stray far from the political center to realize that heavy government involvement within the broader financial industry will likely choke off much of the quality of life that most Americans have come to enjoy since the end of the Volcker era. Is there a better way?Our frustration with the current financial system mirrors that of many Americans, and the conventional banking system is too dependent on interest rates to sufficiently withstand economic turmoil. We must reiterate that the only way to truly build wealth is through investing (which, yes, includes positions in bonds when rates are high), and the sad reality is that most Americans have been unable to participate in this opportunity. In short:

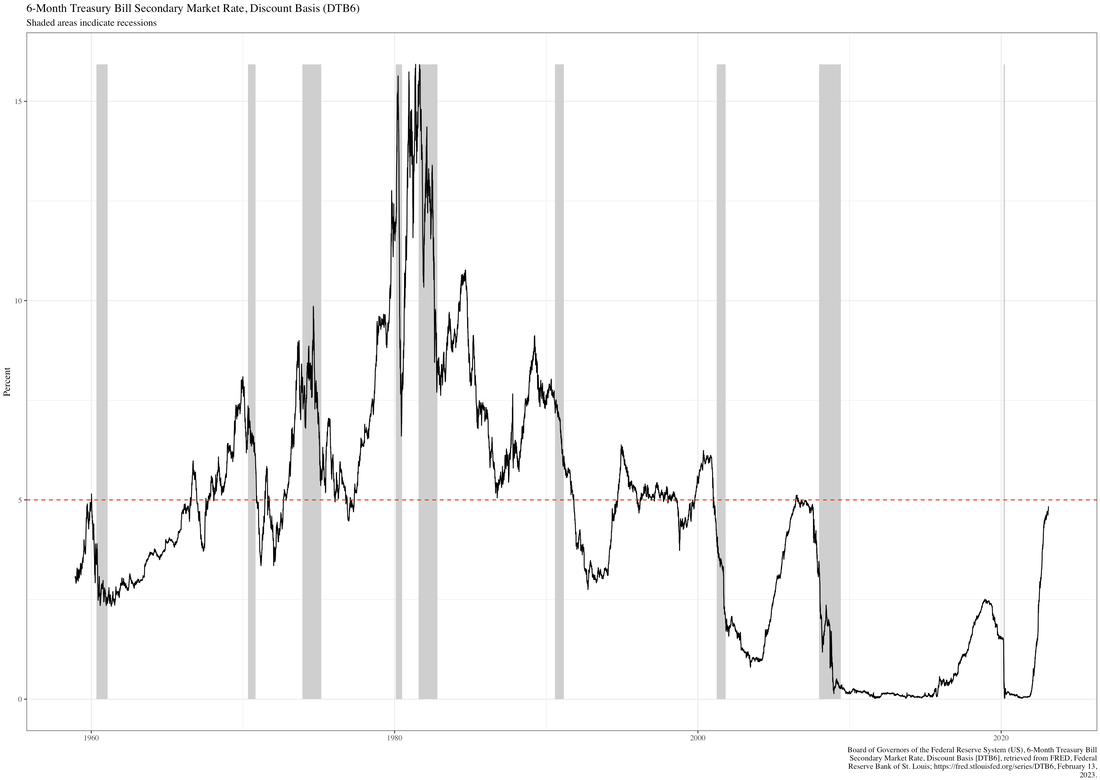

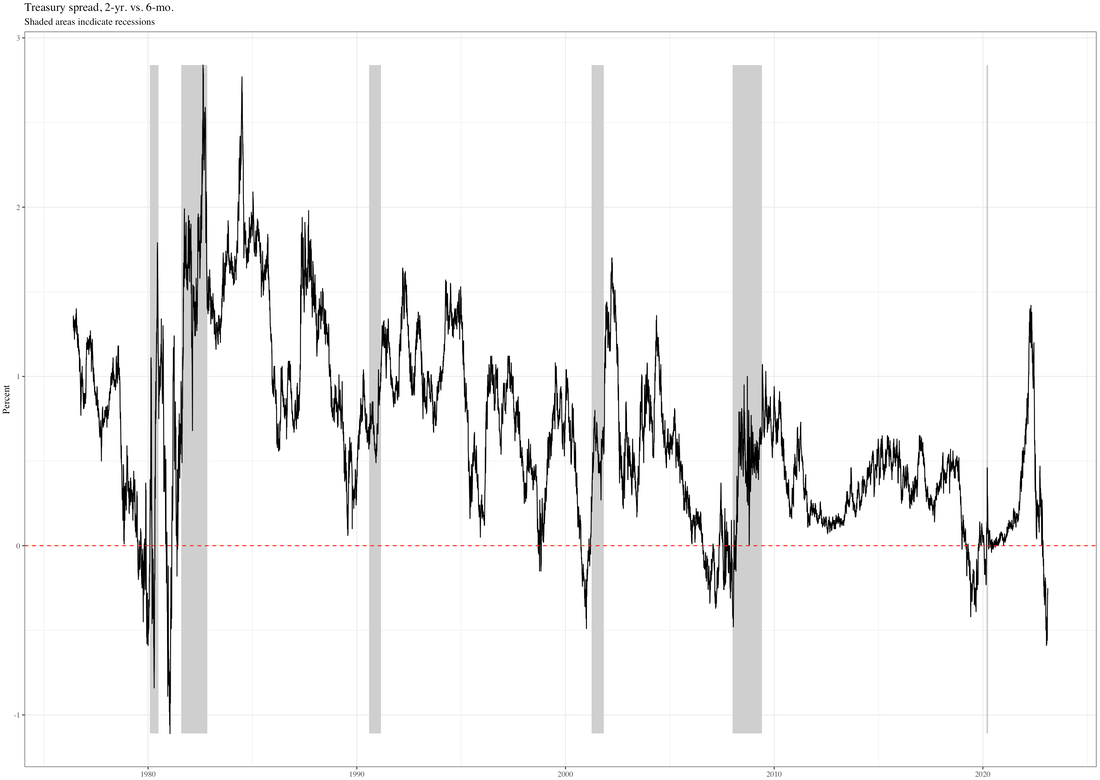

Meanwhile, the Warren Buffet School of Investing – to focus solely on companies with strong economic moats and sound management – has once again proven its worth, which is why our Garrison portfolio was up 4.46% despite 2022 being one of the worst years for the S&P 500 in its entire history, and with a turbulent Q1 thus far in 2023, we're up 12.23% YTD. In comparison, S&P 500: +2% YTD, Dow: +1.49% YTD, and NASDAQ: +2.32% YTD. How does this benefit the average American? We're launching our new company, FinancX, which will become the new standard for finance. Our first product (a first of its kind) will be a hybrid lending model which means you don’t have to invest or pay interest, because we’ll do it for you. With our structure, the market performance of the portfolio dominates fluctuations in the interest rate environment: a fixed portion of every monthly payment is applied to a loan’s principal, and a fixed portion is invested in a diversified portfolio that we manage for you. And the portfolio is called “Garrison” for a reason: a garrison is a military contingent assigned to defend an area – in this case, we’re using our portfolio to guard your wealth. Signups are available (non-binding) to learn more and for you to be one of the first to join the new era of finance that will finally bring responsible capitalism. We already have $25M of soft commitments in just two-weeks. Learn more here. The continued abuse of our financial system is causing it to malfunction.By Willie Costa and Vinh Vuong The cracks of our financial system are beginning to show fundamental weaknesses that indicate most of what we’ve always assumed might be coming to an end. Unfortunately, this would be a failure of seismic proportions that would adversely affect the lives of hundreds of millions of Americans. We’ve never been shy about our bearishness, especially when it comes to irresponsibly tinkering with the greatest and most powerful macroeconomic machine in the history of humanity, but some items as of late beg the question of just how disconnected from reality people can be before opinion turns to delusion. Carl Quintanilla, a highly experienced and decorated journalist, recently shared a tweet that makes one wonder precisely what’s being put into the coffee over at Wells Fargo. To be clear: the bear market is not over, and there is no bull “stuck in traffic” amongst irrational P/E ratios and downgrades. The market’s exuberance over the possibility of rate cuts is like a drowning man deluding himself that splashing frantically counts as swimming and inhaling more water as a result. The Fed is nowhere close to ending their rate hikes, and yes, we are still in an inflationary cycle. Of particular concern is the behavior of the six-month Treasury, which Quintanilla helpfully points out hasn’t been this high since 2007: Of course, the picture gets more dire when one looks at the rate spread between the ten-year and two-year Treasury bonds – the oft-mentioned and occasionally much-maligned yield curve – which has reached an inversion not seen in nearly forty years: This inversion (the above graph indicates the spread between ten-year and two year T-bonds: , which is often taken as an indicator of a recession, although it seems that, historically, the rebound from an inversion correlates better with the start of a recession) is a simple barometer for the health of the economy: so long as the return of the ten-year bond exceeds that of the two-year bond, the economy is said to be in a normal working state (because investors will demand a higher rate of return for their money being invested for a longer period of time). When the yield curve inverts (i.e. investors want a return now instead of years from now), it’s usually indicative of expected tough times in the near term. Unfortunately, the 2-10 isn’t the only yield curve inverting at the moment: Yes, you have read that graph correctly: right now, the yield on the six-month Treasury exceeds that of the two-year Treasury. And, again, this phenomenon is of a magnitude not seen in forty years. At some point, the relationship between interest rates and economic cycles becomes tautological, but it’s rather staggering how often the simplest things are the hardest to accommodate. After all, “everyone knows” that rates have to hike to cool down the economy after a period of rapid inflation (say, for instance, a “hypothetical” one caused by irresponsible government spending during a pandemic and then subsequent ignoring of an increasing CPI…), yet some of the industry’s most intelligent experts not only seem surprised by the reactions of the economy, but also seem eager to paint a picture of “all is well” despite twenty-year high levels of consumer debt (and increasing rates of serious delinquency – perhaps Michael Burry has not yet left the building) and still-raging inflation. We are living in an age where eggs cost more than meat, automakers rake in profits from artificially-constrained supply causing monthly payments to soar… and of course, this causes the knock-on effect of reducing mobility options for the most economically vulnerable, who subsequently have their options for advancement reduced: climbing from poverty to the penthouse is not impossible – Chris Gardner did it – but the trip sure gets a bit easier when you have safe and reliable transportation to get you there; particularly terrifying is that more than half of our college-educated population – the very people who are supposed to be the Leaders of Tomorrow – are staking their chances of financial stability on federal debt forgiveness. The state of our economy may be politely referred to as something that is antithetical to the vision of the Founding Fathers. Of course, these are the macro movements. In the world of microeconomics, where most Americans live, things are equally dire. Aside from the aforementioned spikes in prices, total household debt stands at nearly $19 trillion. Mortgage loans considered in serious delinquency (i.e. past 90 days) – everyone’s favorite disaster from 2008 – have increased to 0.57%: low, but still double from the previous year. Not known for missing out on a great catastrophe, auto loan delinquencies and credit card have increased at twice the rate as mortgages. While the media crow about low unemployment, prices have remained stubbornly high, which has led to rate hikes that will test the ability of consumers to repay their debts. Meanwhile, consumer credit card debt is skyrocketing to levels even higher than the post-2008 spike. This shouldn’t be a surprise: higher inflation leads to higher prices, but when wages don’t rise accordingly consumers are tempted – or forced – to rely more and more on credit just to make ends meet. The only cure for this debt is either paying it off (not always likely, given our culture of “buy now, pay over the rest of your life”) or a strong and sudden contraction that forcibly reduces the aggregate debt load, usually via charge-offs, layoffs, and other hardships best avoided. Note that it’s not necessarily the scale of debt that should matter – after all, debt is one of the critical factors that help an economy expand and also (perhaps ironically) helps expand personal and corporate wealth – it’s the scale of debt given other economic factors that serve to give one pause. In this case, increasing the debt load to help fund purchases (many of which, like food and fuel, are somewhat necessary for survival…) in an already inflationary environment will create a feedback loop that only increases inflationary pressure. This is why we’ve reiterated that a soft landing is not only unlikely, but probably impossible; this is made worse by an illogical (but wholly understandable) focus on job growth numbers in an effort to distract Americans from the edge of the cliff. Some say that the Fed’s 2% inflation target is unrealistic without crashing the economy, and that the central bank should be targeting an inflation rate in the 3-5% range but refuses to do so out of fear of losing face. There may be some substance to this – the US inflation rate has been relatively constant at between 0-5% since 1960 – and the inflation rates of most first-world “benchmark” economies (e.g. Switzerland, South Korea, France, Canada, Singapore, Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) have spent happy decades remaining relatively stable within a tight oscillatory band. Yes, excursions happen and are to be expected, and the tightly-knit nature of a global economy mandates that economic turmoil eventually drags multiple nations down with it, but so long as the past twenty years of Argentina’s inflationary catastrophe of an economy can be avoided, most would consider it a victory.

But why target 2% inflation? In theory, it could be 4% or 8%, but the key would be consensus. A 2% inflation target has not only been the US policy since Ben Bernanke, but has been the official or de facto target of the European Central Bank and similar institutions since the 1990s. Changing our inflation target would be meaningless without cooperation from other central banks, and a good inflation target will keep economies stable without unfairly penalizing innovation. The delicate balancing act is that central banks need margin to cut inflation without collapsing the economy, causing a deflationary spiral and subjecting the US to japanification – the slow economic death that stems from consumers refusing to consume. The closest we’ve come to this since the Great Depression was the 2008 collapse, and that was likely quite enough economic “excitement” for most people. The simple fact is that people forget – or have been made to forget – that the economy is supposed to work for them and not the other way around. But there exists a solution that will truly evolve an industry that hasn’t seen much change in the actual products for centuries. Yes, there have been advancements in the technological side of finance, almost all of which have been revolutionary, but the core products have not changed much outside of index funds thanks to Vanguard and the Bogleheads. We at Garrison Fathom are working on this solution as you read this. Our products will drive responsible capitalism while giving people something they could never have imagined: the chance to use their debt to create generational wealth. Lending, investment banking, and how we live and retire will change forever. Stay tuned and subscribe for updates by emailing [email protected]. When you’re right once, you’re lucky; when you’re right often, you’re despisedBy Willie Costa & Vinh Vuong

Many analysts have said much of 2022 was unpredictable or unusual, but it was a turbulent year regardless. Although it’s obvious that nobody can precisely predict the economy along with unforeseen events (e.g. Ukraine-Russia War), the economic writing on the wall was quite clear. It was basic ignorance, denial, or downright stupidity for anyone to not have seen what we saw with crypto, inflation, the housing market, and lackluster leadership in Washington. We at VUONG Holdings and Garrison Fathom saw it coming from day one as seen in our previous pieces throughout 2022. So here we are. The start of a new year is often a wonderful time for reflection as well as prediction, and perhaps the most rewarding facet of this is being able to look back and see where you got it right. With that said, here are some thoughts on the year we’ve left behind and some forecasts for the year ahead. The Crypto Winter Was Forecasted The line between investing and speculating has never been thinner than when it comes to cryptocurrency. For the fundamentalists, 2022 was a bittersweet combination of ultimate market revenge combined with multiple “I-told-you-so” moments bathed in seas of red ink. It was also the year that future economic sociologists will study intensely as the moment when most of the world completely lost its damn mind. As we’ve mentioned and have discussed multiple times, there are only three ways to build wealth: interest, dividends, or capital appreciation. “Everything else is a ponzi,” which in hindsight seems eerily prophetic as the world finally learnt the answer to what Bernie Madoff would look like if his fashion sense were as ragged as his investment thesis. One of the cornerstones of investing is as true now as it was when the Dutch East India Company became the first publicly-traded company: if it’s too good to be true, it probably is. The optimists would be tempted to think that after 400 years we would’ve all finally learnt its lesson; and as usual, the optimists would be wrong. We praised SEC Chair Gensler’s op-ed and his nuanced approach to the issue of crypto regulation – a far more balanced and elegant response than we might have given to an “industry” that’s shown itself to be little more than an international cabal of technorati utterly divorced from reality and the vagaries of human nature, whose high-minded visions of a decentralized future have so far only increased the scale and efficiency of criminality. The one bit of good news for rational investors is that, much like winters in Westeros, the crypto freeze is likely to last for years. Even proponents of “corruptocurrency” are predicting an extended freeze, maybe even permanently. We are hopeful that once it thaws the world will have sufficiently sobered to examine the potentials of crypto with more discerning eyes. The Tangled Mess of the Economy The interplay between GDP and unemployment is so broadly-understood that it’s tautological to even bother writing a piece on it. But the important things are always simple, and the simple things are always hard. The “not seen in forty years” series of economic chaos has given rise to increasing mention of something else not seen in decades: stagflation. The delusion of “transitory” inflation has conspired with the lowest labor participation rate in 40 years, and while political sycophants praise the ten million jobs created during President Biden’s first two years in office, people conveniently forget that the pandemic wiped out twice that many jobs in a single month. It’s arguable that at no other time in history has truth been more relative than right now – ironic since this is the age when the sum total of human knowledge is constantly available at our literal fingertips, on $1,000 disposable pocket computers that are orders of magnitude faster than what used to be called “supercomputers.” This is an age where the rationalist would be given plenty of reason to think that with so much data available, there’s not a single falsehood that could survive. But, in the words of the esteemed mathematician John Allen Paulos, “Data, data everywhere, but not a thought to think.” Never has hiding from the truth helped a single soul, but alas, we live in the era of identity politics where reality is fluid and innumeracy is only a deficiency possessed by The Other Guy. Our cries of stagflation were, at best, met with raised eyebrows; our claims that the Fed’s tepid rate policy was only delaying the inevitable were declared alarmist; yet now pundits are being given the media attention they so richly deserve for speaking the truth: we are in a recession “by any definition,” we are headed for a potentially-severe downturn, it is going to be painful, and at this point it’s probably unavoidable. There is no polling strategy, op-ed, interview clip, or any mathematically defensible analytical technique that can pervert the truth any longer. In a very dark, masochistic fashion, this is exactly what we deserve. The mechanics of economics are often at odds with the dreams of politicians, because – much like in physics – actions of monetary policy cause inexorable reactions on a macroeconomic scale. Cut rates and inflation will tend to rise; raise rates and inflation will tend to slow; enact toothless monetary policy sheepishly, like Oliver Twist begging for more macro stability, and the political spin machine will turn the wealth of Americans into confetti. The Spaghetti Bowl of Pain An economy is much like a freight train: difficult to influence, but once accelerated (or slowed) it becomes equally difficult to counteract. Yet this past year has given us examples (e.g. China’s abrupt Covid Zero reversal) of world leaders treating their economies like yo-yos, gleefully whipsawing them back and forth seemingly without care. The fact that so many on Wall Street and in Washington got 2022 so wrong gives many a heightened sense of unease. Jobs have been added on hollow hopes that 2023 will be better, inflation continues to bare its fangs while the Fed offers nibbles in return, and the yield curve inversion continues to deepen. The rationalizations for why these are all signs of progress may be politely termed ephemeral. Here is the brutal truth: the economic well-being of the world in general, and of our fellow Americans in particular, is in serious danger. Our leaders have built an altar to delusion upon a tangled mass of massaged data, misspoken statistics, and outright fantasy – a spaghetti bowl of wishes, compromises, and lies. We have forsaken Volckerian discipline for the comforting promises of free money and a better tomorrow without even the decency to question whether these hopes were logically sound. For our insistence upon political expediency and the crime of our hubris, 2023 will be a year of reckoning, perhaps the opening salvo in a long barrage of downturns and a slow and painful return to rationality. Brace yourselves and stick to core principles, because realistically you have no other choice. |

CategoriesArchives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed